Reimagining Palestine by inserting the human dimension

By Khaled Diab

The outside world primarily see Palestinians as two-dimensional heroes or villains. A new generation of artists and writers is adding a vital third dimension, the human.

Monday 3 March 2014

The Arab-Israeli conflict has cast such a long shadow over the Palestinians that it sometimes seems the outside world can only view this dynamic and diverse people through the prism of the conflict. This tension between the image of the Palestinian as freedom fighter, in one narrative, and as terrorist, in the other, distorts the far more important picture of the Palestinian as human being.

But recent years have witnessed the emergence of a new generation of artists and writers who are challenging this superficial hero/villain dichotomy by delving deeper into the ordinary human experience, albeit under extraordinary circumstances.

In so doing, they are making the conflict the backdrop, rather than the central focus. “I have met people, many Palestinians, whom I have found quite heroic in a quotidian, no-glory kind of way,” reflects Selma Dabbagh, a British-Palestinian lawyer-turned-novelist and playwright. “They need to be fictionalised, as the media, if it saw them at all, would be more likely to see them as victims, which is a flattening vision.”

And despite the temptation to communicate a “message,” Dabbagh has striven to avoid such two-dimensional flatness in her work. “I did start writing thinking [I have] a mission… but the more I wrote fiction, the more I realised that the message was dangerous,” she notes. “The characters have to live and breathe in a writer's mind and rub off each other with love and conflict.”

And “love and conflict” are the themes of Dabbagh's latest work, a BBC radio play. Although The Brick, which is set in Jerusalem, features checkpoints and permits, these provide the background scenery to a personal story of mundane routine pierced by shattering family revelations.

In Dabbagh's well-received debut novel, Out of It, she also attempts this difficult juggling act of making the human speak louder than the sometimes deafening background drone of conflict.

Partly set in Gaza during the second intifada, the book strives to rise above the cacophony of conflict to delve into the human experience of a family of “returnees” trying to find escape, each in their own unique way – in England, in the Gulf or inside their minds.

Escapism, exile and return are, unsurprisingly, recurring themes in contemporary Palestinian literature, whether fictional or factual, as brought vividly and poetically, and sometimes humorously, to life by Mourid Barghouti's I Saw Ramallah and I Was Born There, I Was Born Here.

But for real laughs, both tragicomic and absurdist, one should turn to architect-cum-writer Suad Amiry. Set during the second intifada in Ramallah, her debut autobiographical work blends dry, unvarnished humour with a sharp talent for storytelling.

Sharon and my Mother-in-Law hilariously juxtaposes two authoritarian figures restricting Amiry's freedom: one a 91-year-old matriarch, the other a ruthless general-turned-politician in his 70s. “I ended up with two occupations, one inside the house, in the form of my mother in law, and another outside the house with Sharon's army. And don't embarrass me and ask which one was more difficult,” she joked on a long bus journey during which she reflected on life, architecture, politics and writing.

As if to answer her own question, Amiry adds, “Perhaps one day I may forgive you, the Israelis, for all the atrocities you have committed against us, but I shall never forgive you for having my mother-in-law stay with me for 40 days under curfew – which felt like 40 years.”

As the Israeli army locked down Ramallah in 2002, Amiry's mother-in-law was largely oblivious to the war zone around her, retreating into the protective shield of her marmalade-making routine. “In spite of the fact that we were under curfew, with no electricity and no TV, she still wanted to lead a normal life: dress up as if we were going to a party, set the table nicely and eat on time as if there was no war around us,” the perplexed daughter-in-law recalled.

To escape the fighting and curfew on the streets, Amiry mined this rich comedic material in e-mails sent out to her niece and friends which eventually became an unexpected hit when turned into book form, and not just in Europe but also in Israel.

The surreal moments Amiry recounts include a spontaneous outdoor “party” during which all her neighbours took to their roofs to bang on pots and pans in peaceful, if noisy, defiance of the curfew, and an incident in which she posed as her pet dog's chauffeur to get into Jerusalem because Nura, the canine, had a Jerusalem pass while her mistress did not.

As if to prove that this was no beginner's luck, Amiry, who is not only an architectural conservationist by profession but is also dyslexic, has followed up this success with highly innovative, original works.

In Nothing To Lose But Your Life, Amiry disguises herself as a man and embarks, with a group of illegal Palestinian workers, on an improbable, funny, dangerous and self-deprecating adventure into Israel in the dead of night. For her third book, she casts off her male disguise to explore life for middle-aged Palestinian women of the “PLO generation”, intriguingly titled Menopausal Palestine.

Efforts to reimagine the Palestinians through humour do not end with literature. A group of enterprising young Palestinians and Europeans is working on a humorous television soap opera, a genre long dominated by Egypt and Syria. “It's a way of putting Palestinians on the map,” explains Pietro Bellorini, the director of the series. He adds that the production, which revolves around the lives and antics of an East Jerusalem family, will go beyond the serious but superficial Arab preoccupation with the occupation and familiarise the region with the funny and absurd side of life in this troubled and incredibly complex city.

Like Monty Python revolutionised the way we look at the crucifixion by reminding us to “always look on the bright side of life”, humour can play a powerful role in changing people's consciousness through laughter. “We use humour because it is a very powerful tool,” Bellorini stresses. “It is a tool that allows you to say things that wouldn't be accepted in a serious conversation.”

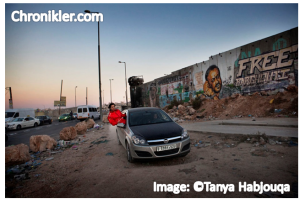

Beyond television, the visual and audiovisual arts are also doing their part to challenge prevalent perceptions. One recent example of this was a photographic project titled Occupied Pleasures, which attracted significant international media attention.

“Pleasures” is not a word most people associate with occupation. But the series features pleasurably unexpected images that shatter clichés, from hijabi women doing yoga on a West Bank mountaintop, to a tête-à-tête between a young man and his sheep in his car, to Ramallah girls getting ready for a night on the town, to Gazan bodybuilders striking poses, to a girl surfer waiting for a liberating wave to ride.

Speed Sisters Trailer (in Production) from SocDoc Studios on Vimeo.

Challenging prevailing stereotypes about Palestinian women has become a regular theme in numerous works. One prominent example is the documentary-in-the-making about the Speed Sisters, Palestine's first all-female motor racing team.

“The first time I sat behind a steering wheel, I felt in control,” one of the Speed Sisters confessed to me. “Now every time I push down on the accelerator, I feel like a bird: free and fast. I feel like I want to move towards the future and break free of all the oppression and repression.”

This longing to “break free” is, as you might expect, a common theme in Palestinian filmmaking, as captured in Elia Suleiman's bleak and beautiful black comedy Divine Intervention, on love in the time of checkpoints.

Recent years have seen a surge in creative, critically acclaimed and award-winning Palestinian films. Even Hollywood seems to have, at least partly, overcome its traditional bias toward “reel bad Arabs” and has nominated the same Palestinian director, Hany Abu-Assad twice for an Oscar: for Paradise Now in 2006 and this year for his thriller Omar. Both delve into the human aspect of political violence, exploring the dark and the ironic.

“If you look at any time in history when politicians have failed, it's the artists who have come forward to try to make sense of the world,” Abu-Assad told the audience at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque.

—

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This article first appeared in Haaretz on 25 February 2014.

your piece was excellent by the way…

“Menopausal Palestine”. Genius!