Minorities in Belgium: From the margins to the mainstream

Minorities in Belgium have become prominent and successful in every walk of life, yet they eye a resurgent and radical racist right with a sense of trepidation, especially as elections loom just over the horizon.

When I first moved to Belgium more than two decades ago, the country's public face was overwhelmingly white and its public domain was dominated by native-born Belgians. This was in spite of the reality that Belgium had already been a multicultural and multi-ethnic society for some time, which I saw around me, especially in the patchwork tapestry of Brussels, one of the most diverse cities on the planet, where I first lived. However, this change had, so far, failed to infiltrate the upper echelons, held down by the glass ceiling of discrimination and held back by the time lag between arrival on the peripheries of society and their (oft begrudging) acceptance in the mainstream or near it.

Today, in contrast, Belgium's public sphere is far more pluralistic and representative of the country's make up, though this may distort the fact that minorities continue to suffer disproportionately from poverty and unemployment. And just as minorities s are becoming more deeply woven into the social fabric, resurgent racism and nativism reflect a desire on the radicalised right to rip them out again.

It required a huge supply of grit, determination and chutzpah on the part of the trailblazers to smash through the walls put up by mainstream society, as well as to overcome the restrictions and internalized prejudices of their own communities. Some of these pioneers were born rebels, some achieved rebel status and some had rebelliousness thrust upon them.

Meyrem Almaci, who in 2014 became the first person with a minority background to lead a Flemish political party — the green party Groen — was a reluctant rebel. “I was rebellious because I had to be. If I had not rebelled, then I would never have studied, would never have ended up in politics and would never have graduated from university,” she told me from her office in the Flemish Parliament. “Throughout my life, I've had to fight against people's expectations for every choice I made.”

Thanks to this fighting spirit on the part of minorities, alongside growing acceptance from the mainstream, people from minority backgrounds have made it to the top in politics, culture, entertainment, the media, sport, business and academia. Some have even become the public face of Belgium abroad. This is especially true for sports. Shortly after I moved to Belgium, there were at most a couple of minority players in the squad for the 2002 World Cup in South Korea and Japan. Today, Belgium's national football (soccer) squad has an abundance of players descended from immigrants, such as Romelu Lukaku, who has Congolese roots, or who are of mixed heritage, such as Axel Witsel, whose mother is Belgian and whose father is from Martinique. Then there are the disguised minorities, the “white” players with foreign roots, such as Yannick Carrasco, whose father is Spanish. Some Belgian-born players of foreign heritage also played for other countries, such as Morocco whose squad at the 2022 tournament counted 14 foreign-born players. At the 2018 World Cup, 10 of Belgium's 24-man squad had immigrant roots.

In music and film, artists with foreign or mixed roots have become some of Belgium's hottest cultural exports. One notable example is Stromae. Ever since his breakout global hit Alors On Danse (And So We Dance) in 2009, which deceptively combined an upbeat dance tune with downbeat lyrics about personal and social problems, the Rwandan-Belgian artist has become arguably Belgium's most famous musician on the world stage. Behind the camera, Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah, both of Moroccan descent, made the transition from Belgian cinema to Hollywood, directing such films as Bad Boys for Life and Batgirl (which has the dubious distinction of being one of the highest-budget films never to be released).

The political landscape, in particular, has seen a seismic shift. At the turn of the millennium, politics was still largely a game for straight, middle-aged white men. There came a period of token minority figures, sometimes referred to locally as “Alibi Alis,” who were recruited to focus on ethnic issues and who often took positions closer to the white majority than their own communities.

The first politician from a minority background to break through to the very top of the political game was Elio Di Rupo of the Parti Socialiste (Socialist Party). He became, in 2011, the country's first prime minister with non-Belgian roots — in his case, Italian.

The fact that Di Rupo is “white” and European may make this seem a minor milestone today, but when the former premier was born in a squatters' camp for poor Italian immigrants in 1951, Italians in Belgium faced much the same prejudice, stereotyping and discrimination that later waves of immigrants would confront. Yet because they arrived earlier and shared the majority religion, this bygone era of marginalisation and exclusion has largely been forgotten today.

With his signature bow ties, Di Rupo also belongs to another marginalised minority: homosexuals. He became Belgium's and the European Union's first openly gay premier, and the modern world's second openly gay head of government. And in surreal and idiosyncratic Belgian fashion, he did so after the country broke another world record: 535 days without a government (coinciding with the financial crisis). Di Rupo managed to resolve the political impasse and navigate the country through the choppy economic waters.

Almost a decade later, Belgium appointed its first Jewish (and female) prime minister, Sophie Wilmes, albeit in a caretaker capacity. She also came to office during a coalition formation crisis in which Belgium broke its own world record for the longest period without an elected government (which overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic).

Another leading politician descended from immigrants, who came from the rural backwaters of their country of birth to Belgium, is Almaci, whose parents moved from Anatolia in Turkey to Flanders. Almaci led Groen for eight years from 2014 to 2022, but there was nothing inevitable about her rise to political prominence, a role she had to hew out for herself as a reluctant rebel.

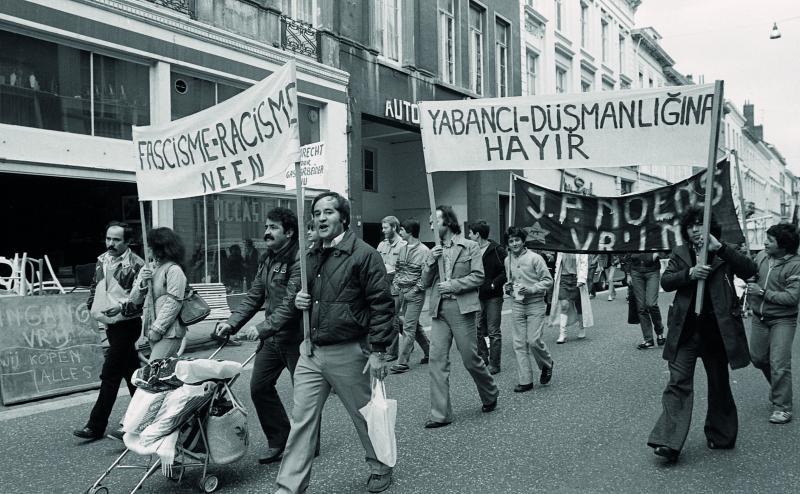

If Almaci had followed the trajectory of so many women of her generation from Belgium's Turkish minority, she probably would have wound up being a housewife and/or doing a menial job. To shape her own destiny, she had first to defy and overcome the low expectations both of society at large and of her own community. The first generation of Turks, like “guest workers” from Morocco and other countries, began to arrive in Belgium in the 1960s, a little later than the Italians and Spaniards, to help plug labour shortages in the mines and industrial cities. They tended to be from rural areas, and under- or uneducated when compared to their urban compatriots. Almaci's mother and father had not even completed their primary education.

Almaci's own family came over to work in the textile sector in and around the city of Sint-Niklaas, but larger Turkish communities settled in Ghent to work in the city's manufacturing sector. It was a far cry from the Fortress Europe immigration policy we know today. In the 1960s, companies, factories and mines were desperate for labour. Consequently, Turks and workers of other nationalities were first granted a tourist visa and then received a work visa once they landed themselves a job. In some sectors, such as the mines of Limburg, special agreements were forged with the Turkish government (like the Italian government before it) to provide a constant supply of migrant labour. Conscious of the post-baby boom demographic dip — and worried about Germany, the Netherlands and France competing for foreign workers — Belgium began encouraging Turkish migrants to bring over their families so they might stay longer in the country and work. This policy decision is still despised by the far right and provides some of the fodder for unfounded, fantastical and paranoid conspiracy theories, such as the Great Replacement, which posits that Europe's political elite is wilfully and intentionally engineering the extinction of the so-called white race.

Belgium's focus at the time on importing low-skilled labour led to the systemic stigmatisation of immigrants as poor and ignorant or uneducated. This, coupled with unconscious bias, unspoken racism and nativism, resulted in a culture of low expectations and marginalisation for the children of immigrants in the education system — a legacy that still colours thinking to some degree even today.

I got an inkling of these stereotypes when I first moved to Belgium in the early 2000s. Quite a few people I came across, especially those who rarely encountered immigrants, were surprised, not only that I didn't speak French very well (they assumed I was Moroccan) but also that I was an educated professional rather than, say, a builder or mechanic. This was quite a contrast from my childhood and youth in London, where people were more likely to assume I was wealthy and didn't always believe me when I contradicted this Arab stereotype. But, then again, Arab residents of the British capital were often either well-off and from the petrostates of the Gulf, or middle-class professionals from other Arab countries.

The higher visibility of minorities in the entertainment industry has gone some way to smashing lazy stereotypes and illuminating the rich festival of humanity lumped together under reductionist labels. “I think it's important to show that diversity exists within diversity,” reflects Serine Ayari, a stand-up comedian, actress and TV personality of Tunisian origin. “That is something that people don't always get or appreciate — that we're not all the same.”

Ayari is secular, outspoken and risque in her comedy. “In my shows, there are many underlying messages which I try to convey to the audience in a funny manner,” she told me from Paris, where she was performing in the shadow of Notre Dame, in a show themed on her own life.

Remarkably for a comedian, Ayari does stand-up in three languages: French, Dutch and English. Her favourite comic language, she informed me, is English, but she's doing a lot less of it now because of Brexit. Between French and Dutch, she prefers to do gigs in French because, in her experience, Francophone audiences are more open-minded and tolerant than Flemish ones. In Flanders, she is best known for her participation — as both a contestant and a jury member — in the tongue-in-cheek quiz show De Slimste Mens ter Wereld (The Smartest Person in the World) and for her role in a comedy series entitled De Luizenmoeder (The Lice Mother).

“To be honest, I don't perform much in Flanders,” she says. “In Flanders, I have to explain what I'm doing there. And that's not something I necessarily want to do. In contrast, if I play a gig in French or English, in Wallonia, in France or in England, there it's a more common phenomenon, and so I'm not the only one.”

That being said, the situation in Flanders is evolving rapidly, as reflected by the success of Kamal Kharmach, who presents, among other things, an annual televised comic review of the previous year on New Year's Eve.

Although Ayari is keen on shifting perceptions with her comedy, she does not see it as her mission to change and fix the world. “You sometimes think to yourself, ‘You know what, that's going to be my challenge,'” she says. “But at other times you think, ‘Fuck this, I've been searching my entire life for my place. If I can find my place more easily in Brussels than in Antwerp, then I'll perform in Brussels.'”

Ayari's personality and stage persona are a far cry from the stifling stereotype of the meek and timid stay-at-home Muslim woman.

“People assumed that I would marry young and I would not pursue higher education,” Meyrem Almaci recalls. “Even the Turkish community expected that girls would not study too much. … They expected that we would become housewives.” And many of Almaci's classmates did just that — built a career at home, raising children. She laments the unactualised potential and unused talents of so many Turkish- and Muslim-minority women from her generation in Belgium.

Like so many children of immigrants in Belgium, Almaci was guided toward technical school by both the education system and her family. Yet she resisted these low ambitions with a ruse. Instead of going to technical school as everyone expected, she enrolled in general secondary education without her parents' initial knowledge and against the advice of guidance counsellors. To do so, she took her older sister along to meet her headmistress, with the invented excuse that her parents were visiting Turkey. The school director accepted her application, and her parents forgave her transgression. In retrospect, Almaci sees this as the most pivotal moment of her life.

Although Almaci was exceptional in how well she managed to swim against the current and defy the norms of the time, she was not an exception. A significant minority of minority women have managed to overcome the prejudices of society and the constraints within their own communities to blaze a trail to success.

One good example of this is Badra Djait, who is the diversity and inclusion coordinator at the University of Ghent and leads or is involved in several grassroots community and arts initiatives. Djait's Algerian parents did not go to school. Despite this, or because of it, they were keen that their children should receive a top-notch education.

“People are impressed when they look at my family because neither of my parents can read or write due to the fact that they were born under colonisation, yet they managed to raise seven kids who got university degrees,” explains Djait. “And the fact that we are all girls, except one boy, doesn't fit people's preconceptions. The fact that we went out to explore the world, as it were, with one living in Australia and the other in the US, and so on, defied people's expectations.”

Achieving this involved not only navigating the uncharted territory of higher education, but also grappling with the issues thrown up by greater independence and freedom for women. Going where no Djait had gone before required a great deal of self-reliance and resourcefulness, but it paid off. At school, Djait pursued one of the most prestigious and demanding streams, Latin with sciences. At university, she managed to earn two degrees, one in Arabic and Islamic studies, and the other in social and cultural anthropology. After a period as an academic researcher, Djait entered politics as a ministerial adviser and then as a parliamentary officer, and even stood for local elections once.

Likewise, Almaci began her career as an academic researcher after graduating from university with a bachelor's in social work and a master's in comparative cultural studies. When she decided to enter politics, she again collided with the wall of rigid expectations and pigeonholing. “People expected me to focus on asylum and migration and employment opportunities for minorities,” she recalls. “I was lucky enough to be in a party which had different expectations from women and minorities.”

Groen's flexibility allowed Almaci, who had previously been a member of WWF and Greenpeace, to pursue her interest in making the Belgian economy more sustainable by becoming an opposition member of the Federal Parliament's finance and budget committee where, during the banking crisis, she pushed for tougher banking regulations. At the helm of the party, she led Groen to a better election outcome in 2019 than in 2014, despite the right-wing populist onslaught against the party and the conservative dominance in Flanders. But the hoped-for “green wave” did not occur.

Media reports focused on the internal divisions within Groen to explain Almaci's resignation as chair, but she emphasises the perceived need for renewal within the party and her personal desire to focus more on her family and private affairs. Another factor that influenced her decision to step out of the spotlight, she admits, was the bigotry and hatred to which it exposed her. Not only did society judge her more sternly, as a woman from a minority background, than her white male counterparts, she was also the target of a relentless deluge of invective and abuse. “Almaci gone? Good. Groen gone? Even better!” tweeted Tom Van Grieken, the head of the far-right Flemish nationalist party Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest).

“Meyrem Almaci has become … living proof of how racist and misogynistic part of the Flemish electorate is,” wrote the columnist Walter Pauli in the weekly Knack. “There is not one politician who has been subjected to such a torrent of dirty swear words as she has, especially on social media.”

For Amaci, as for many other women and minorities, social media proved to be one particularly toxic cesspit of misogyny and racism. Abuse “is repeated dozens of times a day with the crudest words, the coarsest insults and even with death threats,” she says. “People don't want a woman with a minority voice like me… People find that I don't belong in the political arena performing such a top function.”

Almaci's attackers didn't let things like facts get in the way of their venomous fantasies. “It doesn't matter what stances I take, people pin things on me that are untrue simply because they want to,” she observes. “It is always about that untrustworthy, Islamist, Turkish witch who supports [Turkish President Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan, who is a friend of terrorists, and so on.”

Had Almaci been a middle-aged white man, society might have looked on her moderate success at the ballot box more kindly, and the attacks from the right would likely have been less personal and vitriolic and more about her politics. But minorities not only have to try harder to make it, they also have to achieve more to be regarded as successes. In fact, in the eyes of many in the majority, prominent minority figures are impostors who rose to the top not because of their talents and abilities, but because of “political correctness” and its younger cousin, “wokeness”.

Overcoming and counterbalancing this disproportionate hostility — without predecessors having cleared a path through prejudice or having normalised success — requires a faith in oneself and a self-assuredness that many find hard to muster. And if much of the outside world regards you as an impostor, it is unsurprising if you start feeling, against your better judgment, a bit like an impostor yourself. This can manifest itself in a variety of ways, some of which are subtle, such as the feeling that you don't really belong in your position.

For example, although many of the best and most successful journalists in history never studied journalism, this apparent gap in her education caused Layla El-Dekmak — a journalist, radio presenter and documentary maker — distress at the beginning of her career. “It took a long time before I dared to call myself a journalist because I hadn't studied that,” she admits. “I felt I didn't have a right to do that and only years after I had worked in the field did I employ that title.”

When El-Dekmak first became a radio journalist about a decade ago, she felt a deep sense of isolation, as one of the only minority voices at her radio station. “It took me a very long time before I realised why it was I felt lonely, why it was I felt like it wasn't right,” she reflects. Although she did not face any overt discrimination at work, she felt the complex and often subtle effects of unconscious bias. “At that time, Radio 1 was a white bastion, which is what it still is today,” she observes. “I saw nobody around me who shared my experiences.”

This ethnic uniformity had unintended consequences. It meant that many of the ideas El-Dekmak pitched during editorial meetings, which resonated with her and would have resonated with minority audiences, failed to capture the imagination of her colleagues and never saw the light of day.

El-Dekmak's sense of alienation occurred despite the fact that she is half-Belgian and has spent almost all of her life in Belgium. Her darker skin tone and foreign name mean that “in Belgium, I will always be perceived as someone with Arab roots, as an old-school immigrant, as a child of migrants. And in Lebanon, I am perceived as someone who is very Western.”

But El-Dekmak's diverse background equipped her with the power of cultural shape-shifting and adaptability. “When it comes to code-switching, I was already there,” she notes. “I was used to navigating all-white spaces.”

This chameleon-like ability to blend in against the cultural background, as well as the sense of being a well-fitting misfit, is familiar to people of mixed heritage and so-called third-culture individuals. The gap between an individual's own sense of identity and their external features can cause a certain amount of dissonance. This is especially the case if their physical appearance contrasts with the look generally associated with their personal identity or if that identity is more complex than mainstream reductionism allows.

In my experience, this is especially pronounced with people who are adopted by parents with a different skin colour. I know Belgians, for instance, who were adopted in Africa or Asia but have spent their entire lives in Belgium and know very little about the societies of their biological parents, yet in the eyes of society they are generally labeled as “black” or “Asian.” One pet peeve some of them have is when strangers compliment them on how well they speak the language, even though it is their mother tongue.

But this also applies to people of mixed heritage and to ethnic minorities. My Belgian-Egyptian son, for example, spent much of his childhood in the Middle East, where his (then) bright blond hair and pale skin not only made him stand out, albeit in a generally positive manner, but the fact that he spoke Arabic like a native bewildered and baffled bystanders, even though people with fair features are not uncommon in the region.

The inverse, the dark-skinned offspring of a pale parent, is usually less well-received, both in Europe and in the Arab world. This is manifest in the way that the white heritage and upbringing of certain mixed-race people (even those as high-flying as Barack Obama) are often ignored by supporters and rejected by racists.

This “othering” phenomenon was on painful display when, during a halftime performance at a soccer match in 2013, a TV presenter once described the superstar Stromae as a “super well-integrated coloured boy.”

This comment was offensive, not just for its condescending racist undertones, but also because Stromae is not some recent immigrant unfamiliar with his adoptive land but a born-and-bred Belgian. Born Paul van Haver in Brussels to a Rwandan dad and Belgian mom, he was raised by his white mother in Belgium. In many respects, he is quintessentially Belgian. “There's something Belgian in me, maybe cynicism or irony or surrealism,” he told an interviewer last year. “We're always a little average — we try to do our best but — .”

As well as dance, rap, Cuban and Congolese music, Stromae's style was heavily influenced by the legendary Belgian crooner Jacques Brel, also from Brussels. And he carries forward in his own unique way the tradition of genre-hopping Belgian singer-songwriters like the late Arno, who mixed rock, blues and chanson. Last year, during one of the farewell concerts before his death, the eccentric, idiosyncratic singer was accompanied on stage by Stromae for a surprise performance of one of Arno's most acclaimed and surrealistic songs, the trilingual “Putain, Putain.” Arno had been one of Stromae's idols when he was growing up, and Arno became a huge admirer of Stromae's music.

Despite the exclusion implicit in the TV presenter's comment about him being a “well-integrated coloured boy,” Stromae took the incident in his stride, striking a conciliatory and forgiving tone. “We all have the potential to be racist in us, all humans do. It's very easy for a racist sentence to come out and it's very easy to point the finger at a person who could have said something accidentally, demonise them forever as if they were evil incarnate,” he said to an interviewer. “I think it's more unhappiness and sadness that translates through racism. You have to learn to dialogue with these people, explain to them rather than marginalise them.”

Stromae's philosophical view of racism and the importance he attaches to dialogue possibly stem from his intimate knowledge of what happens when discrimination is left to fester for generations.

Beyond the quotidian discrimination and typical playground taunts he undoubtedly faced growing up, the singer's life was profoundly and painfully shaped by the legacy of racism. At the tender age of nine, van Haver lost his father, a Tutsi who had returned to Rwanda to set up an architectural office but was caught up in the 1994 genocide. The mass slaughter had its roots in the racial hierarchy that had been established at the end of the 19th century, first by the Germans and then by the Belgians, which elevated the Tutsis above the Hutus. This caused widespread resentment, which colonial authorities attempted to appease by transferring power to the Hutus shortly before independence, but which led to brutal repression of the Tutsis after the Belgians left.

The extreme trauma of losing his distant father in such a cruel and hateful manner had a powerful influence on van Haver as a child and, later, on the adult Stromae's music. For instance, in “Papaoutai” (i.e., “Papa, ou t'es?” or “Dad, where are you?”), he sings about a boy who suspects something is wrong when his father disappears and tries to extract the truth about his whereabouts from his mother. In real life, van Haver's mother initially tried to conceal the likely gruesome death of her husband from her kids to shield them from the painful truth, even while holding down two jobs to keep the family afloat as a single mother.

Stromae broke down and cried on TV during his first African tour when asked about the Rwandan genocide. “It touched me and it still touches me to see that we don't quite manage to live together yet,” he said in front of a live studio audience.

And the question of whether we can quite live together — of coexistence — is high on the minds of minorities in Belgium, as they watch with hope and fear the dual trends of growing acceptance and tolerance alongside deepening racism and bigotry.

Emblematic of both how far Belgium has come and how far it still has to go are the politicians from minority backgrounds who have found their way into political parties associated with traditional identity or nativism. Nevertheless, they too often still serve as Alibi Alis or progressive fig leaves behind which regressive policies can be concealed.

This trend is epitomised by the nationalist Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie (New Flemish Alliance). While its archrival, the far-right Vlaams Belang, embraces a blood-and-soil version of nationalism, the N-VA is willing to accept people of non-Flemish descent, so long as they fully exemplify the party's narrow definition of what constitutes a Fleming and subscribe to its anti-Walloon, anti-immigrant, separatist agenda.

For example, Zuhal Demir, who is of Turkish Kurdish ancestry, has risen to the highest echelons of the party. Although she is now the Flemish minister of environment, justice, tourism and industry, her previous portfolios (including equal opportunities and combating poverty) enabled the party to push an ultraconservative agenda while dodging allegations of xenophobia. This was in part thanks to Demir's spirited denial that her party is racist. She is also a fully paid-up passenger on the anti-woke gravy train, like her party chief, Bart De Wever, who somehow found the time (despite or because of the crisis and scandals plaguing his party) to pen a polemical book that preposterously claimed, in a Trumpian-like projection, that “wokeness” was pushing the country towards civil war.

Another, more centrist, example is the Iraqi-Belgian politician Sammy Mahdi, who recently became the leader of the embattled and crisis-ridden party Christen-Democratisch en Vlaams (Christian-Democratic and Flemish). Even though Mahdi's mother is Catholic and most Belgians abandoned going to church a couple of generations ago, the fact that his father is a Muslim would not only qualify him as belonging to that faith in the eyes of millions of Muslims, it would not so long ago have disqualified him from leading the once-dominant centre-right Christian party in the eyes of its members and voters. This traditional attitude was expressed by a bishop who asked during a documentary about Mahdi whether it was right that a Muslim should lead the Christian Democrats. “But I'm not a Muslim. I'm agnostic,” Mahdi retorted.

To rise to the top and appeal to conservative voters, Mahdi had to ride roughshod over his immigrant background and play up his local roots. His chosen strategy, when he was secretary of state for asylum and migration, was to continue the hardline xenophobic policies of his predecessor, Theo Francken of the N-VA, even vowing to implement more and faster deportations. This uncompromising treatment was symbolically expressed in the months-long standoff between Mahdi and 475 desperate asylum seekers who went on hunger strike in a Brussels church as a last-ditch effort to have their paperwork regularised.

While I'm not naïve enough to think that the son of an immigrant should automatically be sympathetic towards asylum seekers, Mahdi's tough line on refugees appears bewildering considering that his own father had returned to Belgium as an undocumented migrant to escape a death sentence for refusing to perform his military service under the regime of Saddam Hussein. Instead of attempting to seek asylum, Mahdi's father married the Belgian woman (Mahdi's future mother) whom he'd dated while they were at college together.

The contradiction and irony were not lost on the interviewer in the documentary mentioned above. “That's crazy, that the former secretary of state for asylum and migration is the son of an illegal refugee who should have actually been sent back,” the interviewer observed. Mahdi admitted that, had he been in charge of migration at the time, he would have sent his father back to Iraq.

More worrying still is that strident anti-minority and anti-immigrant discourse and policies are creeping and seeping ever leftward. A prime proponent of this is the young leader of the centre-left Vooruit (Forward) party, Conner Rousseau, who has consciously modelled his style on Denmark's Social Democrats. Although Mette Frederiksen, the Danish prime minister, is best known on the other side of the Atlantic for her refusal to sell Greenland to the erratic and temperamental former US President Donald Trump, at home she has borrowed liberally from the right-wing playbook, especially when it comes to minorities, immigration, refugees and Islam, but has married this to relatively progressive socialist policies.

What this scapegoating masks and conceals, however, is that the truly poor integrator is not immigrants but the state and society. Despite undoubted progress in many areas, the state remains partly unwilling and partly unable (due to electoral considerations and structural issues) to truly integrate minorities and render them full and equal citizens, substantially as well as formally.

The fact that more people of a minority background are out of work and poor is not down to individuals' (ir)responsibility or their refusal to participate, but the government's failure to put in place effective policies, especially its failure to combat structural discrimination. “How is it that study after study show that, in Flanders today, if you're from a minority background and have a university degree, you are more disadvantaged than a Fleming with a high school diploma, that you get fewer job opportunities?” asks Almaci.

A 2021 experiment commissioned by the local council in Ghent, the town where I live, sent out nearly 2,000 fictional applications to open job vacancies and found that, all things being equal, people with immigrant roots were 16% less likely to be invited to an interview, while the situation was even worse for transgender people, who received 29% fewer invitations.

And though the second- and third-generation descendants of immigrants are generally better integrated, newcomers face an enormous uphill struggle. Despite a booming economy in 2022, with a record number of new jobs and labor shortages in a multitude of sectors, Belgium scored among the worst in all of Europe when it came to getting immigrants from outside the EU into employment. Only half are in work, a recent study by the University of Ghent uncovered. Moreover, nearly 40% of non-EU migrants in work are in a job below their schooling level. “Across the entire chain — starting from influx, reception, housing and education — things go wrong in Belgium,” observes Mark de Vos, one of the authors of the study.

Instead of putting forward effective policies for making better use of immigrants, Rousseau has joined the chorus blaming them for the faults of the system. In so doing, he has shown little compunction about throwing Belgium's minorities under the bus in a misguided attempt to attract an increasingly right-wing Flemish electorate to left-leaning policies.

The wannabe populist has, among other things, claimed that he did not feel like he was in Belgium when he drove (without bothering to stop) through the disadvantaged area of Molenbeek in Brussels, which has a large immigrant population. Rousseau has also berated what he claims is the poor integration of immigrants and their alleged refusal to learn the local language or teach it to their children. For that reason, he wants to make attending nursery school compulsory for babies, from the age of 6 months.

He's not above insinuating that recent immigrants are parasites. Rousseau has disingenuously alleged that while Belgians see claiming benefits as a last resort, a Public Centre for Social Welfare (OCMW) “is too often the first step for newcomers,” echoing the overused far-right trope of the immigrant as a sponger off the state and hardworking natives, even though the Belgian pensions and welfare system would have collapsed long ago without immigration.

The resurgence of the far right and the rightward drift of both the center and left have caused concern among minorities as they look toward 2024's triad of European, federal and regional elections. If voters in Flanders headed to the ballot box today, the Flemish nationalist right would capture half the votes, with the openly racist Vlaams Belang emerging as the largest party, while leftist parties would capture about a third, even with Conner Rousseau's conscious pandering to right-wing sentiments, according to a poll released in May. The situation is less troubling in Wallonia, where the largest party is the Parti Socialiste (Socialist Party).

“The rise of the extreme right is very scary, really terrifying. It's happening all over Europe and I've been waiting in fear for the past few years,” confesses El-Dekmak. “I think it is underappreciated just how frightened minority groups are of the next elections.”

El-Dekmak finds the radical right worrisome not only because of its racism and rejection of minority rights but also because of its climate denial and anti-feminism. “We hold human rights in high regard in Europe, but they are not as much of a given or as entrenched as we believe they are,” she adds.

Some are more hopeful that the hard-won gains of recent decades can be built upon and enlarged. “I'm not convinced that there is more racism now than before,” says Badra Djait. “It used to be quite normal, for example, for a pub to hang up a ‘no foreigners' sign… Being sworn at on the streets was normal. The bus driving straight past you because the driver didn't want to pick up foreign passengers: That was also normal.”

“I view the future positively, but I'm also naturally optimistic,” Djait adds. “I see the future positively precisely because of the young generation that is far more engaged socially, that embraces diversity much more, is very open, and also wants to do something to change things.”

In my own view, the present moment is extremely fluid and increasingly polarised. Rather than being on the cusp of a more progressive future, we may actually be experiencing a kind of Weimar Republic moment, with the fascists readying themselves in the wings to storm the stage and upturn everything we hold dear. Less dramatically, we may slide further down the slippery slope toward an entrenched authoritarianism founded on xenophobia and racism. A truly sustainable, progressive, diverse, tolerant and empowering future is also achievable. And the much-maligned members of Generation Z are our best hope for achieving it, even though they too have some racists and reactionaries in their ranks.

However, many dark social, economic, political and technological clouds loom on the horizon. Overcoming these will require, among other things, an end to the scapegoating of minorities and a reckoning with the real causes of falling living standards, such as the growing concentration of wealth that is undermining social cohesion. What we desperately need are progressive policies that grant all individuals the welfare and dignity they deserve.

_______

This essay first appeared in New Lines Magazine on 17 July 2023.

Pingback: Minority report in Belgium - The Chronikler