When a Christian king and a Muslim caliph united against their common foes

Despite the official holy war between Islam and Christendom, Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid and Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne exchanged lavish gifts, including an elephant named Abu al-Abbas, and built a largely forgotten alliance. This reveals how Christians and Muslims can simultaneously be foes and friends and how sharing a religion is no guarantee of peace, just as belonging to different faiths is no assurance of war.

There once lived two emperors who ruled over two of the grandest empires of their time and whose names would resonate for centuries to come as legendary embodiments of what was supposedly noble and brave in Christendom and Islam. Even though Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne, also known as Charles the Great or Karl der Grosse (c. 747-814), and Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid (c. 763-809) were officially enemies in a cosmic conflict between good and evil, believers and infidels, they acted like long-distance lovers with bottomless pockets, lavishing on each other luxurious and beguiling gifts.

These two monarchs may not have shared a common religion but they shared the kind of geopolitical and economic interests that stretch across the porous and elastic civilisational lines, magically transforming the infidel into the very embodiment of fidelity. Through the exchange of several embassies, the Frankish king and the Abbasid caliph sought to deepen the alliance first forged by Charlemagne's father, Pepin the Short (c. 714-768), and al-Rashid's grandfather, Abu Jaafar al-Mansur (c. 714-775). Charlemagne took the initiative and was first to send an envoy, even though al-Rashid's father, Abu Abdallah al-Mahdi, had indirectly been the cause of a humiliating military defeat for the Frankish monarch.

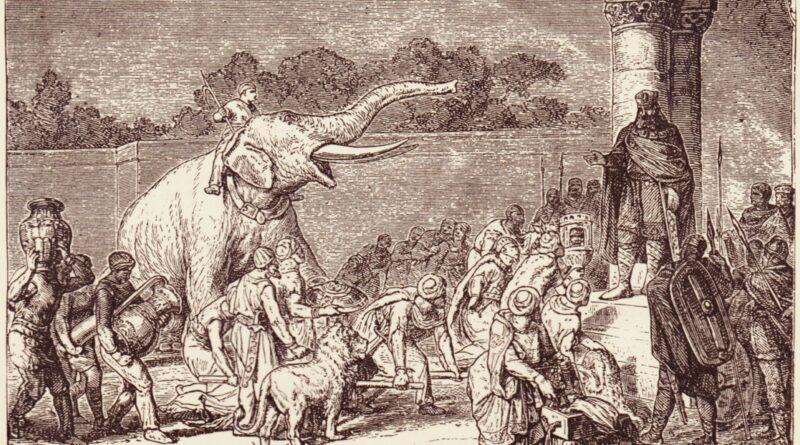

In return for high-end red fabrics and other luxuries sent by Charlemagne, Harun al-Rashid dispatched silken robes, fragrant perfumes, aromatic spices and, of all things, an exotic elephant, an animal possibly unseen in Europe since Hannibal crossed the Alps to take the battle to his Roman enemy.

This elephant was known as Abu al-Abbas, like the first Abbasid caliph. Charlemagne became so enamoured of this beast that he reportedly took it with him on many of his campaigns. It made the emperor's heart break that his beloved Abu al-Abbas died the same month as his eldest daughter, Rotrud, in June 810.

But the gift which drew the greatest gasps of astonishment in Charlemagne's court, and for centuries to come in Europe, was a sophisticated water clock. Almost a millennium before the invention of the cuckoo clock in Germany, this water-powered timepiece was a masterpiece of contemporary engineering.

“All who beheld it were stupefied,” confessed Notker the Stammerer, a Benedictine monk and author of Gesta Karoli (The Deeds of Charlemagne).

The Royal Frankish Annals of 807 described the clock as:

A marvellous mechanical contraption, in which the course of the 12 hours moved according to a water clock, with as many brazen little balls, which fall down on the hour and through their fall made a cymbal ring underneath. On this clock there were also 12 horsemen who at the end of each hour stepped out of 12 windows, closing the previously open windows by their movements.”

The Royal Frankish Annals

The relative sophistication and extravagance of Harun's gifts in comparison with Charles's reflected the relative might and technological progress of the two polities over which they ruled. The Abbasid empire at the time of Harun was around 11 million square kilometres while the Carolingian empire over which Charlemagne held sway was a tenth of the size, at around 1.1 million square kilometres.

The Abbasid empire, which was probably the wealthiest and most powerful realm of the time, was a scientific and cultural powerhouse of the medieval world. This was visible in the splendour of the newly founded imperial capital, Baghdad, which lay close to the site of ancient Babylon.

Although Harun had moved his court temporarily to Raqqa in Syria (to be close to the Byzantine frontline and the restive Syrian tribes), Baghdad remained the empire's cultural, intellectual and economic capital and became the capital once again following his death. With an estimated population of somewhere between 1 and 2 million, which made it possibly the largest metropolis in the world at the time, the city housed the famed Grand Library of Baghdad (Bayt al-Hekma or House of Wisdom), as well as a multitude of philosophers, scientists and poets from around the world. It was also reputedly home to a thousand physicians and an enormous free hospital, an abundance of water (valuable in this dry region), thousands of hamams (public baths), a comprehensive sewage system, banks and a regular postal service.

In the inner circle of Baghdad lay the palace of the Golden Gate, which was originally envisioned by al-Mansur as an integral part of the city centre. This surprised a Byzantine visitor who, while praising al-Mansour's new city, also criticised the fact that “your subjects are with you inside your palace”.

“Since you see fit to comment on my secret,” al-Mansour reportedly replied drily, “I have none from my subject.” However, after a foiled attempt to foment an insurrection, the caliph heeded the Byzantine's warning and decided to move the market away from the palace and shifted his residence to a palace on the other bank of the Tigris.

In contrast, Charlemagne's capital, Aachen, which lies in modern-day Germany, near the border with Belgium and the Netherlands, was a far more modest affair, not even counting among the largest cities in Europe. First established as the Roman spa town Aquae granni, the name morphed into Aachen via High German ahha (water or stream). Charlemagne chose it for reasons strategic (to be near his empire's heartland), political (to leave Rome to the pope) and military (to be close to the restive Saxons).

To ensure his new capital befitted his stature as the “new Constantine”, Charles abandoned the Germanic practice of having a mobile itinerant court and built a permanent palace in Aachen. While Charlemagne's residence was likely relatively modest compared with Abbasid excess, members of his court were convinced otherwise.

Echoing the high praise lavished by Arab poets on medieval rulers, Notker the Stammerer claimed that a delegation from Baghdad who visited Aachen in 802 considered Charlemagne to be “so much more than any king or emperor they had ever seen” and that when the Frankish king gave them a tour of his incomplete palace, “the Arabs were not able to refrain from laughing aloud because of the greatness of their joy.”

The laughter may have, indeed, rung out for the reasons given by Charlemagne's biographer – and these seasoned ambassadors were overjoyed by the scale of the 1,000m² aula regia or council hall where visiting dignitaries were welcomed. Then again, there are many reasons why people laugh. The Abbasid envoys may have been laughing out of politeness or even out of polite mockery at the relative lack of splendour.

As one of the Arabic language's most celebrated poets, that supreme flatterer of kings, al-Mutanabbi, put it:

If you see the lion's canines

Don't think it smiling

More charitably, the Arab envoys may have been genuinely impressed by how relatively humble Charlemagne was in giving them a personally guided tour of his home and inviting them to dine at his table, while their own king, Harun, reputedly met foreign diplomats and dignitaries from behind a screen.

So why, despite the geographical, religious and power chasm separating them, did Harun al-Rashid and Charlemagne seek to forge an alliance?

For the simple and complicated reason that the Carolingians and Abbasids had two common and highly tenacious enemies: the Umayyads and the Byzantines.

The Umayyads, who had ruled the realms of Islam until they were overthrown during the Abbasid revolution, which occurred around the time Charlemagne was born. This had driven the last remnants of the Umayyad dynasty westward, where they set up a rival caliphate, centred in Cordoba, in a classic display of what I call the clash within civilisations.

The Abbasid-Umayyad beef was over who should rightly call themselves ‘caliph', i.e. the successor of Muhammad. The caliph was originally selected through a tumultuous process known as shura (consultation), but the Umayyads succeeded in turning this elected office into a dynastic, hereditary title. The Abbasids, who rose to power on the back of a popular revolt against the Umayyads, did not question the undemocratic nature of their predecessors, because they too wished to rule dynastically, but, instead, attacked Umayyad exclusion of non-Arab Muslims and the dynasty's alleged moral failings. Ironically, the Abassids eventually became Islam's first absolute monarchs and lived in even greater splendour and seclusion than the Umayyads.

Though the Umayyads had become largely a political threat to the Abbasids, they were, from their new base in Cordoba, a territorial threat to the Carolingians. In fact, Charles Martel, Charlemagne's grandfather, held them back at the Battle of Tours/Poitier, saving Gaul from being subsumed by the Umayyads. Nevertheless, the Muslim rulers of Spain continued to be a menace to the Frankish king's territories and territorial ambitions.

Nevertheless, it was a Muslim ruler, by the name of al-Arabi, no less, who convinced Charlemagne, before Harun al-Rashid had even ascended the throne, to invade Spain. Sulayman ibn Yaqzan al-Arabi, the pro-Abbasid ruler of Barcelona, fearful of Umayyad expansion northward, backed by other Abbasid-aligned Arab chiefs in northern Spain, called, in 777 AD, on the aid of Charlemagne, whom, at this point, appeared invincible. To tempt the Frankish king, they claimed that the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, al-Mahdi, Harun's father, had promised to support the proposed expedition with an invading force.

Decades earlier, the inverse occurred at the other end of the Iberian peninsula when Julian of Septem and other Visigothic rivals of the unpopular Roderick, who ultimately became the last king of the Goths in Hispania, persuaded Tariq ibn Ziyad to invade Iberia.

However, Charlemagne's campaign in 778 AD was, unlike Tariq ibn Ziyad's, a humiliating debacle. Charles crossed the Pyrenees at the head of the largest army he could muster and, after a brief stop at Barcelona, headed toward Zaragoza. However, the ally he expected within the city walls, due to the Umayyad caliph in Cordoba Abd al-Rahman's amassing of a massive counterforce, had a change of heart, and the turncoat turned coat again.

This pattern of constantly shifting alliances, in which Christians and Muslims were sometimes foes and at other times friends, was to mark the next seven centuries of Muslim presence in Iberia. Similarly, the Crusader kingdoms that sprang up in the Middle East during the Crusades, which kicked off at the end of the 11th century, were similarly embroiled in a constant ebb and flow of shifting allegiances. This is partly because the idea of a unified Islam or Christendom was always aspirational and never a reality, as reflected in everything from the so-called Apostasy Wars following the death of Muhammad, which almost spelled the end of his nascent ummah (nation), to the sacking of Constantinople by crusaders in April 1204. While religion can occasionally motivate state action, it is one (often minor) factor among many, and is often trumped by geopolitical interests, convenience and opportunism, power struggles between neighbours and supposed allies, historic ties that predate the advent of the two rival religions, or simple sympathy or empathy between two leaders on opposing sides of a supposedly civilisational divide.

Take the curious case of Raymond of Tripoli. A speaker of fluent Arabic who was widely read in Islamic literature, Raymond, despite having earlier spent a decade in a Syrian prison, forged a temporary peace with the fabled Saladin (Salah-Eddin al-Ayubbi) and allowed the Kurdish leader of Egypt and Syria to cross the Galilee and set up a garrison in Tiberias.

The official Crusade/Jihad notwithstanding, and even though Saladin was engaged in an Islamic version of the Reconquista, a baffled Andalusian traveller who passed through the Levant wrote: “There is complete understanding between the two sides, and equity is respected. The men of war pursue their war, but the people remain at peace.”

The other mutual enemy the two emperors shared was the Byzantine empire, which was a territorial rival to the Abbasids, with a shifting frontier between the two warring empires in the Eastern Mediterranean, and a political menace to the Carolingians, who did not share a border (besides Venice, which was nominally a Byzantine duchy) but did share aspirations for ruling Christendom. The Abbasid weakening of the Byzantine empire territorially served Charlemagne's interest, while any dent to the political reach and stature of the Byzantine empire inflicted by the Carolingians served Harun al-Rashid.

When Irene of Athens became the first woman to rule over the Byzantine empire after the death in prison of her son and co-regent Constantine VI, Pope Leo III, driven by misogyny and opportunism, proclaimed Charlemagne emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, arguing that the throne was technically vacant because a woman was not permitted to rule. This weakening of the status of the Byzantine empire was music to the ears of Harun al-Rashid and the Abbasids.

But common enemies is not all that bound the Carolingians with the Abbasids. There was also old-fashioned economic interests, especially as Charlemagne was keen to attract Abbasid dirhams under his “open market” policies. Some economic historians posit that the lavish gifts accompanying the embassies exchanged by the two emperors had the ulterior motive of developing new consumer tastes and, hence, export markets.

According to Arab geographers of the time, there was an active trade between the two empires. The Abbasids exported luxury goods, such as spices, silks and even, surprisingly, top-grade Gazan wine, which was gradually being muscled out by the improving wines of Gaul. The Carolingians exported mostly commodities, including beaver skins, furs, lead and coral, as well as more valuable goods like rugs, clothes and perfumes. Most shockingly and surprisingly from our modern perspective is that there was a heavy flow of slaves and eunuchs from Carolingian Europe to the Abbasid world. Most of the humans trafficked by the Carolingians at this time were Slavs, and it is from this medieval trade that our English word ‘slave' ultimately derives. The Vikings and Venetians were also known to sell European slaves to the Abbasids.

Despite the mutual interests and realpolitik that defined their relationship, Charlemagne and Harun al-Rashid, though they never met, had surprisingly much in common. Both were born to rule and groomed to lead Christendom and Islam, at least in their own estimations. Charlemagne's dream was to be a king who would be remembered as a just and honourable ruler. Harun, as his honorific al-Rashid (the rightly guided) revealed, was also haunted by similar concerns about his legacy. Both Harun and Charles also viewed themselves as the virtuous representation, even embodiment, of their respective faiths. One way they expressed this is through holy war, or military campaigns ostensibly aimed at spreading the faith at the point of the sword in the lands of the infidel.

For Harun, that was the Byzantine empire, against which he launched two large-scale invasions of Asia Minor. The first occurred in 782, when Harun was still a prince, and saw the heir apparent ostensibly lead a campaign which reportedly cost as much as the entire Byzantine empire's annual income. Harun led his army to just across the Bosporus Strait from Constantinople itself, but was almost defeated on his march back, had it not been for the aid of an Armenian prince who had defected earlier to the Byzantines, only now to shift his allegiance back to the Abbasids. This victory, and the tribute from Empress Irene which accompanied it, cemented Harun's reputation as a capable military leader, despite his only having nominal command over the Abbasid forces.

The 806 invasion of Asia Minor was even larger than the one in 782. It was prompted when Irene's successor, Nikephoros I, tore up her peace agreement, refused to pay the tribute to Baghdad and launched raids against the Abbasid frontier. Incensed by this defiance, Harun decided to punish the Byzantine emperor, and succeeded not only in re-imposing the tribute but also in forcing Nikephoros to pay a personal tax.

While Charlemagne had, as mentioned above, some skirmishes with the Muslims of Spain later in his reign, Frankish Christianity at the time was more interested in conquista than reconquista. Rather than reclaiming the traditional territories of Christendom, Charles sought to conquer new lands and bring them into the Christian fold. Back then, and this is something that is often forgotten today, Christianity was as new to many parts of Europe as Islam.

Charles aimed to change that by bringing Christianity to the ‘pagan' Saxons and Slavs, among others. In the course of the Saxon Wars, spanning three decades and 18 campaigns, he conquered Saxonia and proceeded to forcibly convert it to Christianity, despite steadfast Saxon resistance. The Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae, a legal code issued by Charlemagne to govern the Saxons which sound remarkably like a precursor for the later inquisitions, prescribed the following: “If any one of the race of the Saxons hereafter concealed among them shall have wished to hide himself unbaptised, and shall have scorned to come to baptism and shall have wished to remain a pagan, let him be punished by death.” In 782, the same year as Harun's shock and awe campaign in Asia Minor, the Frankish king committed the infamous Massacre of Verden, which involved the beheading of 4,500 Saxons, while 10,000 others were deported with their wives and children.

The Abbasids were also involved in religious persecution, including later of ‘heretics' who refused the rationalist explanation of the nature of the Quran, but Harun al-Rashid's policy was more intermittent and pragmatic than Charlemagne's. This was partly ideological, as Muslims were not supposed to persecute fellow People of the Book, originally Christians and Jews, but widened by the Umayyads to include Zoroastrians and Buddhists. On more pragmatic grounds, Ahl el-Zemma (Dhimmis), were profitable for the state treasury because non-Muslims' second-class status was reflected in not just accepting Islamic rule but also paying a special pole tax, known as al-jizyah. Moreover, narrow religious zealotry and fanaticism would have made an empire as large as al-Rashid's ungovernable and relative tolerance was paying off handsomely for the Abbasids, in the form of the flourishing sciences, arts and commerce. That being said, the oft-crippling financial burden of being a non-Muslim, combined with structural discrimination against non-Muslims and popular prejudice, coerced many non-Muslims, particularly Persian Zoroastrians, to convert “voluntarily” to Islam.

Another thing Charlemagne and Harun had in common was posthumous reverence. The two men lived on after their deaths as swashbuckling heroes of folklore and popular tales. A fictionalised version of Harun al-Rashid was eternalised in the expansive annals of the 1,001 Nights. In these popular tales, the caliph is not a distant and cloistered figure out of touch with his people but is, rather, a humorous eccentric who cares deeply about his subjects, so much so that he secretly circulates amongst them at night to learn about the issues concerning them. Whether or not the real Harun al-Rashid, who was accustomed to living in the lap of opulence and luxury, actually slummed it with his subjects is questionable but the fact his subjects believed it earned him enormous admiration.

Harun's colourful entourage also features in the 1,001 Nights, with the most colourful undoubtedly being Abu Nuwas, the camp court poet.is At a time when Charlemagne's clergy was busy condemning and equating homosexuality to bestiality and persecuting homosexuals, Abu Nuwas was singing the praises of and trying to seduce “handsome beardless young men, as if they were youths of the gardens of paradise” in fictional tales and real life.

Although Persian-Arab Abu Nuwas is depicted as something of a joker and court jester in Arab folklore, in reality, he was so much more. More irreverent than Oscar Wilde, always ready with a witty and scathing riposte, and a proud hedonist, Abu Nuwas was the original rebel without a cause – or his cause was to mock and defy social convention and highlight its hypocrisy and prejudice, especially against non-Arabs. He revolutionised Arabic poetry by ditching the nostalgia for romanticised Bedouin life and replacing it with themes suited to the cosmopolitan, multicultural and urbane Baghdad which was his world.

Abu Nuwas did fall out of favour with Harun al-Rashid, and had to hot tail it to Egypt. But Harun's displeasure seems to have been aroused not by Abu Nuwas's odes to gay love and wine but by the verses he penned lamenting the downfall of the powerful Persian Barmakid family, which had administered the empire on behalf of the caliph until Harun decided, in a moment of whimsical caprice, to rid himself of his longstanding allies because they had become too powerful and rich.

Like Harun al-Rashid, Charlemagne became the star of numerous medieval fictions and legends, which also combined heroics with no small measure of humour. Charles was one of the central characters of the Matter of France, which ranks alongside the Matter of England as one of the greatest medieval literary cycles. In it, the Frankish king is cast as a kind of French Arthur and his paladins are the French answer to the knights of the roundtable.

Legends from around the period of the First Crusade depicted Charlemagne as the first crusader, a kind of patron saint of crusading, even though he never went to the Middle East and was an ally of the Abbasids against his fellow Christians, the Byzantines. Reimagining or fabricating history in this way had a clear political purpose, it enabled the people of the time to believe that their crusading enterprise had a precedent and that Charlemagne embodied the justness and chivalry of their cause.

One epic poem from the 12-the-century, Le Pèlerinage de Charlemagne (Charlemagne's Pilgrimage), describes Charles and his paladins arriving in Jerusalem, where the patriarch offers the Frankish king a multitude of religious relics and declares him emperor. More outlandishly still, the group of merry men continues on to Constantinople, where the fictional Byzantine emperor, after seeing Charlemagne perform miraculous physical feats, agrees to become Charles's vassal. In 1095, a year before the First Crusade, Ekkehard of Aura, a Benedictine monk and chronicler, reported of stories that were circulating at the time that Charlemagne had actually risen from the dead to lead the crusaders.

Even today, the two men have found themselves reappropriated as important cultural building blocks in cross-border identities and as part of the mortar mix holding together pan-European and pan-Arab identities. Charlemagne, for example, is often referred to as the ‘Father of Europe'. Manifestations of this iconic status include the European Commission's Charlemagne building in Brussels and an EU youth prize named after the Holy Roman Emperor, to name but two examples.

Harun al-Rashid is often held up by modern Arab nationalists as one of the supreme exemplifiers of lost Arab glory. Those dreaming of pan-Arabism, not to mention pan-Islamism, often evoke the memory of the Abbasid caliph, as do Arab dictators. Saddam Hussein, for example, was fond of likening himself to Harun al-Rashid, as well as Saladdin and Hammurabi. Hussein even adopted the Abbasid caliph's 1,001 Nights persona in the early years of his presidency. On television, he would visit factories, schools, mosques, farms and homes, disguised in a traditional kefiya scarf or hat, ostensibly to find out about the situation of his citizens. And, invariably, his supposedly unsuspecting interlocutors would praise his achievements and act all shocked when he revealed his true identity before an admiring world.

However, what the romantic nationalist views of Harun and Charles overlook is that the two emperors were as much dividers as unifiers in the empires they ruled, attacked their co-religionists as much as they defended their faith, and their supposed defence of the faith was mostly about a quest for power, wealth and status.

The myths surrounding al-Rashid and Charlemagne, which depict them as just, honorable and courageous commanders of the faithful, reinforce the idea that Christendom has always been at war with Islam — and, by implication, always will be. But what the history of the two monarchs reveals is that Muslims and Christians can simultaneously be foes and friends, both with each other and among themselves. Sharing a religion is no guarantee of peace, just as belonging to different faiths is no assurance of war.

____

This essay first appeared in New Lines Magazine on 15 July 2022.