Prologue: Writes of passage – #25YearsAJournalist

A quarter of a century ago in Egypt, I became a journalist after years of on-and-off trial and error, punctuated by professional disappointment and personal setback. Here's how my story began.

This year marks my 25th anniversary as a published journalist. However, in reality, my journey did not begin in 1999. It started years earlier, though it was interrupted by repeated disappointments and setbacks, there being no clearly sign-posted route at the time for a young Egyptian living in Cairo wishing to make it in the English-language media, even if I spoke English like a native, was intimate with Arab and European societies and had a knack for words.

If you're expecting a how to become a journalist in five easy steps guide, or even 10, you've come to the wrong place. And I don't really have a glib secret to my success formula for you – that's assuming that what I have achieved counts as success. Instead, this is the unvarnished story of why I wanted to become a journalist, how I tried to achieve that goal, my failures and successes along the way, some reflections on journalism and the world I wrote about, as well as the fun and difficulties I experienced.

Avid reader as I was, I dreamt of becoming a writer in my teens, albeit more a writer of fiction than a journalist, though to be successful in the latter requires powerful storytelling skills. Although I experimented throughout my teens with short stories and some poetry/song, this was almost exclusively for my own consumption and occasionally that of family members and some close friends.

At first, I saw journalism as an entry point to other forms of writing, probably the path of least resistance to getting published. However, the path proved longer and far more resistant than I had at first envisioned.

One early attempt was at university when I tried, along with a group of friends, to get a rudimentary college magazine off the ground. It was shocking to the English side of my upbringing that student had no outlet in which to express themselves and vent, and I wanted to fill that gap. There were two main reasons why my faculty did not have a student publication. One reason was the fact that we lived in a semi-authoritarian society in which the reins on the media were tightly controlled and the state almost had a monopoly on the media landscape.

Given the propensity of students to rebel and foment uprisings, as had been proven in the past and would become clear again a couple of decades later, the state was particularly alert to universities. It was reputed that State Security had informers and spies on campuses across the country, and many people lived in apprehension of being overheard and reported on. Even if the realistic likelihood of this occurring was slim, it served the interests of the state to maintain this atmosphere of fear. This was reinforced by the annual tradition of the police rounding up known activists at the beginning of the academic year, mostly Islamists at the time. Although we were secular, this provided no safeguard against detention or police brutality. And while Islamist students had the mosque in which to convene and build up a collective identity and mutual solidarity, secularists had been robbed of possible venues to congregate and organise.

Another not unrelated barrier was the massive wall of apathy students had built around themselves. The college I studied at, the Faculty of Foreign Affairs in Zamalek, was, at the time, the only place outside the American University in Cairo that taught university-level programmes in English and it was fee-paying, despite being part of a public university. This meant that it attracted a certain elite crowd, not as elitist as the AUC, but drawn mostly from the cosmopolitan reaches of the middle class and the wealthy.

This meant that many students were shielded from the harsh realities of poverty and repression around them but lurking just out of sight. Unlike in the years leading up to the 2011 revolution, when it was in vogue for well off youth to become politically engaged, back in the 1990s, it was trendy to be ignorant and indifferent or feign ignorance and indifference to the troubles of wider society or the world at large. The underlying unspoken message or vibe was to say: “I'm so well off or wealthy that not only am I protected from the harshness of the world, but I live in a big enough bubble not even to notice what is going on.” In addition, many barely read beyond the requirements of their education.

Another cause of the widespread apathy was that disengagement represented as a (semi-)conscious act of self-preservation against a regime that would go to great lengths to eliminate opposition and a social order in which defiance, though pretty common, was both despised and feared by those in positions of authority. This meant that even institutes of higher learning, supposedly the greatest bastions of free inquiry and speech in a society, muted or limited the expressive power of their young charges, or at the very least swept it under the carpet.

Stop press

Against this backdrop, it is unsurprising that we failed to get our student rag off the ground. But I felt it was worth a shot. With a small group of friends, we came up with a name (which I no longer recall), ideas for content, a plan for how we would produce the magazine, approached local photocopying shops to figure out how much it would cost and how much we would need to sell a copy for to break even.

I booked an appointment with the dean to discuss the idea. He listened patiently and informed me that if he were to give his go-ahead for the magazine, then every issue would need to be submitted in advance for vetting to the faculty's admin and we would need to remove any content it deemed inappropriate before publication. I explained that this went against the ethos of the magazine, which was meant to be a free space produced and curated by students for students. The dean insisted that this was non-negotiable.

Afterwards, we decided to abandon the idea. We did not wish to give the faculty the right to censor us, especially as we intended to cover the concerns of students and include humour about our professors and courses. We also decided, after some discussion, not to defy the university and produce an unauthorised publication, partly out of fear of being pursued by campus security or worse.

Although I was disappointed, I was determined not to give up. I resolved to cast my net further afield. However, for someone of my convictions and disposition, the print media landscape was depressing. It was tightly controlled by the state, with the notable exception of a handful of publications, like al-Dustour, which was perpetually getting itself into trouble. This stifling influence robbed the media, especially the broadcast media, of much of its potential for dynamism and energy. As someone who did not wish to succumb to (self-)censorship, the options were vanishingly small.

In addition, my formal Arabic was not strong enough for me to confidently write articles. I had returned to Egypt with a competent enough grasp of spoken Arabic (though much of that was limited to the domestic sphere) but only the fusha my mum had managed to teach me at home, which was primary school level. My first real-world exposure to formal Arabic was at university (but luckily only for a handful of courses) and I struggled to close the gaping chasm that separated me from my peers.

I also suffered from a common problem afflicting young people everywhere looking for employment: to get a break in the media, I needed experience. However, to gain experience, I needed someone to give me a break. This was made all the more challenging at the time because most Arabic-language publications only used journalists who were members of the journalists syndicate.

At the time, I was keenly aware of and lamented the fact that few publications in Egypt explicitly catered for university-aged youth and those that tried to did so in a highly condescending and preachy manner – as though they were written by middle-aged editors and regime stooges. Among the handful of English-language publications, which had greater editorial freedom but a narrower scope, none did.

I decided to approach the most-established English-language magazine at the time, Egypt Today (originally known as Cairo Today), with the idea of starting a youth page or supplement. I managed to get an audience with a member of the magazine's senior editorial team, a young Brit whose name currently escapes me. He loved my pitch and thought a supplement would work better than a page. He asked me if I would be able to produce some sample articles to give the rest of the editorial team a clear idea of what we were planning. Excited, I agreed.

I pitched the idea to my best friend at the time, Ayman, and we enthusiastically teamed up to produce articles about youth by youth. Over three decades and untold words and articles later, I don't recall any longer precisely what we wrote about but I have a recollection that we produced a feature about the Cairo rock music scene. We had been involved as volunteers in the organising of the first edition of a festival known as Monsters of Rock, which was set up by radio DJ Osama Kamal, who bizarrely also worked as a speech writer and translator for Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak. The festival borrowed its name from Kamal's radio show on Cairo FM, which in turn borrowed its name from a UK music festival.

Ayman and I even organised our own underground gig, which was great fun, even if it didn't make us a profit, but it also didn't lose us money, luckily. At the time, there was a moral panic in the media about heavy metal and other forms of hard rock music, and the youth with long hair and black T-shirts who listened to it were quite literally demonised as “satanists” by sensationalists conservatives. We wanted to give the musicians and youth involved a voice.

Dashed dreams and shelved aspirations

As my family was going through the financial mangle following my father's decision to throw us to the wolves of deprivation, providing us with just enough to survive on the margins, we had been forced to sell my computer some time earlier. This meant that I drafted all my articles in long hand on paper and then wrote up the final clean copy in my best hand. The night before our deadline, Ayman and I stayed up till the early hours finalising our supplement, quite literally cutting and pasting the copy (without a clipboard, though) onto plain paper and stapling that together into something resembling a short magazine supplement.

What followed were a few excruciating days of nail-biting anticipation. When I submitted the final product, the editor seemed confident the magazine would go for it. Although the editor had led me to believe that approval of the new supplement would be largely a formality, the publisher vetoed the idea against the counsel of the editors, he told me to soften the blow. Inside, I was fuming but I tried not to show him how furious and frustrated I was. Not only were the time and effort we invested ultimately wasted, but my dream of becoming a journalist was dashed for the time being. Back then, I did not feel terribly charitable towards the editor. Although I did not blame him for the publisher's decision, I felt he could have done more to fight our corner or at least to have given us a realistic idea of our prospects. In hindsight, I am able to be more detached and philosophical about the letdown. It provided me with early insights into how, if you weren't part of the status quo and didn't want to be, there was little space for you and carving out the space would require not just good ideas and creativity but patience and perseverance.

But patience and perseverance were a luxury I could ill afford at that moment in my life. The financial difficulties at home since my father's abandonment of us and my desire to help my mother fill the gap meant that if I wanted to pursue journalism, it would have to be in a way that involved some kind of financial returns. As this was not a feasible prospect, I decided, with a heavy heart, to shelf the idea, where it would collect dust for a few years.

Typecasting and avoiding clichés

Funnily enough, I got into editing before I became a published writer. It happened by accident. One summer, in order to make some extra pocket money and to help out at home, my maternal uncle swung me a job at a friend's document copying and word-processing business. At the time, most Egyptians did not own personal computers but universities were demanding that theses be typed out and printed. Moreover, in certain scientific, medical and engineering disciplines, theses and papers were often composed in English, the lingua franca of international academia.

As I could type and was a pretty dab hand with computers, I had the requisite qualifications for the job. However, it turned out that I had another skill that proved indispensable: native-level English and a talent for writing. An early thesis I was asked to type out was not only incredibly boring but also written in very poor English. I asked the author if he would like me to correct and improve his English as I went along and he eagerly agreed. This helped him produce a better thesis and helped me take the edge off the tedium of typing out the dull document by enabling me to interact actively with the text. And so began one of the idiosyncrasies that would become common for me: doing work for which I had little formal qualification and which I was too young for. Here I was, only an undergraduate myself, helping improve and correct the writing of graduates and post-graduates. The service became so popular that we started charging a little extra for it.

In the actual academic sphere I was in, my writing wasn't always appreciated by my professors. Although the college I was in was meant to be a bastion of modernity in the tertiary education ecosystem, a lot of the faculty, with some notable and welcome exceptions, had a very old school Egyptian idea of the relationship between student and teacher, and quite a few did not appreciate my inquisitiveness and questioning approach, especially the free marketeers amongst them. I was also regularly penalised for my unwillingness and inability to be a rote learner. For some professors, it was not enough to understand the subject matter, you had to recite it using their formulations, sometimes down to the order in which you presented the ideas and the exact wording. This was sometimes ideological (they perceived their interpretation and wording to be sacred) and sometimes pragmatic (they got assistants to mark assignments and exams using an answer key).

This made me somewhat regret my decision to study business and economics for the pragmatic reasons of getting a leg up in a tight labour market as opposed to following something closer to my interests, as my mother had suggested, and studying English literature. Although the dean of the English literature faculty at Cairo University, whom my mother had contacted, had been keen for me to transfer there, I ultimately decided against it, partly because I feared if it turned out to be as rote-based and mechanical as other faculties, I would end up hating reading and books.

One advantage of my decision was that it made finding employment, which I desperately needed, easier. Whereas most undergraduates and recent graduates in Egypt at the time formed endless lines for the limited jobs available, it was employers who queued up at my college, which was the only Egyptian faculty at the time to teach business and economics in English, to snatch up the available talent. Through it, I got training opportunities at the multinational Procter and Gamble and a summer internship at the local franchise of Europcar where my boss was so impressed that he offered me fulltime employment even during term time. There, I focused on setting up a market research unit and helping the IT manager set up and administer the companies sparkling new network which included the novelties of internet connectivity (via dial up), e-mail and even a website.

Writer's block

During this period, my aspirations to be a writer fell by the wayside. It's hard to focus on contemplative intellectual pursuits when you're constantly contemplating how to make ends meet, holding down a full-time job to try to keep those ends from spinning apart and then camping down at the end of each semester to try to squeeze in all the stuff I'd missed at uni before my exams.

That's not to say that time was completely idle for my development as a writer. I gained a diversity of life experiences which I tried to observe with the remote eye of a writer. I also developed my writing skills passively through avid reading. Being in Cairo and with limited funds, I could not always afford to be picky about what I read, especially in English. I was a member of the rather limited British Council library and, after getting through all the books I liked, I read some of the books that appeared less appealing and a few that were outright repulsive. Most of the books I owned at the time came from Cairo's plethora of second-hand bookstands, from the famous Azbakiya book market to Zamalek and other places. You could occasionally find some real gems, but at other times you had settle for the most interesting that was available. I also bought low-cost editions of classics and books on special offer from regular bookshops.

In addition, I tried, on and off, to keep up with the news and important developments. But this was in the days before the web had taken off in earnest and social media did not exist beyond a few basic chat forums. This meant that I could read the local media, restricted as it was. However, I often found the front page always dominated by Hosni Mubarak and the blunted coverage of politics so demoralising at times that I would stop reading the newspaper. One advantage of being exposed to the Egyptian press at the time was that it trained me to engage with news content (or kalam garayid, newspaper talk, as it's known in Egypt) sceptically and critically – to question things and read between the lines.

The local English language press was generally freer, in particular Ahram Weekly and the Cairo Times. The foreign newspapers and magazines that were available were limited in selection and usually beyond my budget, and they were quite often partially censored and some had their own issues of bias. I could afford to buy a foreign newspaper or magazine only rarely and accessed what I could at the library. It also meant that I often ended up reading old news, picking up dated copies at low prices from second-hand stands – giving life to the Egyptian adage, “news that costs money today is free tomorrow”.

In addition, I strove to hone my writing skills by occasionally composing fiction. My bag always had a notebook (of the paper variety) and a book in it, often accompanied by a newspaper or magazine, as I liked to, and often needed to, read and write on the move. Reading, at this stage in my life, was not just about deepening my knowledge of the world, it was also very much about escaping it. At a time when I couldn't afford to travel, books were my low-budget passport to different places and times. At a time when I was often too broke to go out and have fun, reading was a good way to kill time, whether at a café or at home. For the comfort, joy and entertainment the offered, my then-modest but growing book collection at home became my pride possession.

Even with my income, this remained a very difficult phase for my mother, siblings and I. The pittance we got from my father's family combined with the pittance I got from my work sometimes barely lasted us 10 days or a fortnight, forcing us into emergency mode for the rest of the month. Thankfully, my maternal uncle used to help out periodically, enabling us to have the occasional laid-back month and to occasionally do or buy something nice.

The hardships of becoming members of the nouveau pauvre were accentuated by the bruising to one's pride and the sense of humilation caused by the fact that we lived in a middle-class neighbourhood, I went to college with mostly well-off students and many of my friends lived comfortably, while others struggled harder than me.

It was a frustrating time when my life appeared to be going nowhere, except possibly downwards, in a hurry. Despite the despair I often felt, I still harboured a strange confidence that I would, one day, be able to dig my way out of the hole I was in – though I didn't know how deep I was, when or where the opening would appear, and where I would land when I finally climbed out of the rabbit hole.

This confidence was probably partly thanks to the trust my mum had always put in me and the faith she always expressed in the future, a confidence that sometimes annoyed my inner cynic and sceptic. But it more than compensated for the constant criticism and knock downs I got from my father. Another reason, though I didn't get why it was because I felt quite ordinary, friends, colleagues and even bosses often, and uninvitedly, praised by talent, skill or knowledge and encouraged me onwards – something I greatly appreciate in retrospect. But, deep down underneath all that, I guess it was simply a stark choice between crumbling under the weight of despair and despondency or clinging on to the outer ledge of hope, despite my realistic (some say pessimistic) streak.

None of my business

I soon discovered that the business world was not for me, and not just because I disliked wearing ties and shaving regularly, with my immediate boss, who light-heartedly teased me about my stubble, occasionally offering to buy me a supply of razors. I also grew dissatisfied with my employer. Although my direct line manager was both fun and mentored me and the IT manager taught me a lot and involved me in an enjoyable project, the general manager of the company was stiff and tightfisted. Although I was doing highly skilled and valuable work for the company, my pay had not risen very much above what I had been making as a trainee there.

After about a year and a half, I'd had enough and decided to throw caution to the wind. After all, I had almost nothing to lose. I requested a pay rise. It was turned down. I enjoyed handing in my resignation and seeing the shock on the big boss's face – he tried to talk me into staying with vague words about investing in my future and vaguer promises of better days ahead for me (he claimed to be grooming me for the business world), but it was too little, too late. Though still only a business undergraduate, I quit the business world for good.

English and writing were my calling and they were calling to me. As a stop gap, I started teaching at the school where my sister had recently started working. In addition to teaching English to junior school kids, I started a drama club for the kids to provide them with a creative outlet.

A year or so later, I did a certificate (bankrolled by my maternal uncle) that qualified me to teach English to adults, after which I began working at the British Council in Cairo. There, my dream of becoming a writer reawoke from its slumber. However, there were no obvious entry points for an inexperienced aspiring writer.

Once I'd settled into teaching and found my flow, my time at the British Council gradually revived my creative interests and aspirations. This was in part due to the creative types attracted to teaching English as a foreign language, many of whom used the profession as a ticket to travel or as a financial subsidy for their other pursuits, whether literary, journalistic, artistic, thespian, singing or dancing. Some were Arabists, fascinated by the language and culture, and teaching English to bankroll their further and deeper immersion into Egyptian society.

The more secure financial footing upon which I stood also gave me more head space to think creatively and the relative luxury of dedicating more time to act upon it. After a while, the pull of writing was coupled by the push from teaching. It's not that I didn't enjoy teaching but the realisation had grown on me that EFL was a dead-end job, at least for me as an Egyptian.

Not only was I on a so-called local contract, which paid considerably less than for British teachers who were recruited directly by London or moved from another branch, but, at least at the time, there was no prospect for advancement or even to use teaching at the network as a ticket to travel the world. I had only ever heard of one Egyptian who had managed to transfer to a British Council operation in another country and none in management. There was a group of Egyptian teachers who had been stuck at the Council for up to decades and I saw them as a cautionary tale.

Radio silence

For a while, I toyed with the idea of becoming a radio presenter, both before and after I joined the British Council. I knew a couple of DJs at the so-called European Service, including one, Hanan, who was a fellow teacher at the British Council and another, Ashraf, whom I overlapped with at college briefly before he graduated and who had become a friend. They both suggested that I consider applying to join the service. Although I had been invited as a guest a handful of times on air, I wasn't sure if I wanted or was ready to take that leap.

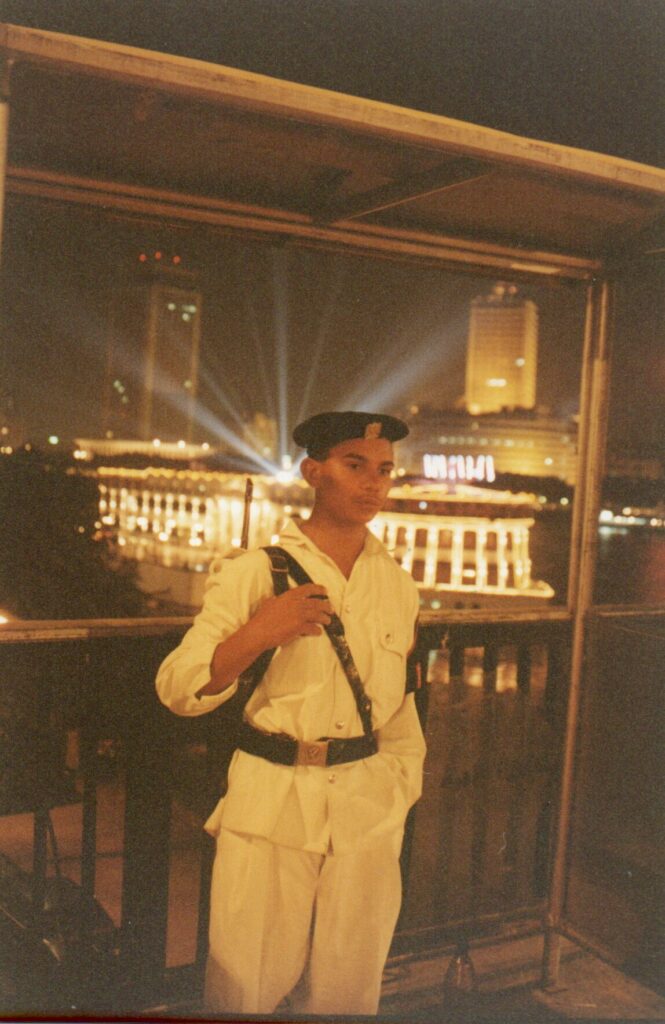

On the plus side, doing radio had a certain appeal to it and I've been told that I have a good radio voice, though I have a tendency to “er” and “um” when I can't find the right word because I like to find the right word, a habit which I have worked to overcome over the years. In addition, there was a nice, laid-back vibe of camaraderie among the staff at the European Service in the crumbling radio studios, which mostly looked like they'd not received new equipment or a lick of paint since the iconic Egyptian Radio and Television Union building on the banks of the Nile in Maspero was inaugurated in 1960. The dated facilities and lack of resources engendered an admirable resourcefulness amongst the staff, who often had to find ways to acquire music themselves if they wanted to play something on air that interested young listeners.

On the minus side, the European service was part of the state-run ERTU behemoth, a small and oft-forgotten corner of it, but part of it nonetheless. Not only would applying involve a Kafkaesque bureaucratic process (though my friends were confident that my perfect English and my style would put me in good stead), it would also mean that I would be working for the government. Not only was the pay shit but it would also involve severe restrictions on what I could say on air and I valued my freedom too much to hold my tongue – also I feared that my tongue could not be held for long, as it had a mind of its own and liked to speak it.

Ultimately, I did not apply to do radio. Had I done so, my career may have turned out to be very different. But, ultimately, writing was what interested me and, for better or for worse, a print journalist is what I became. How that turned out is for the next instalments.