The EU does not need a church wedding

With the EU's economic union more or less consummated, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and his Convention on the Future of Europe have been drawing up the prenuptials for a prospective political union. This must exclude the church.

Marriage is truly in the air. There are, of course, certain members of the EU who blush at calling it a political marriage in polite society. But, for better or worse, that is invariably where it is heading. Just as these cautious amours, after decades of courting, were finally reconciling themselves to the idea of tying the knot, an old scorned lover has to storm onto the scene and embarrass the guests.

Well, actually, Pope John Paul II is in no fit state to be doing any stomping around. Still, his message was clear: he felt slighted and he demanded to be part of the future happy family, too. But is Europe, desperately grappling with the notion of political unification between once fiercely independent nation states, ready for a second marriage between church and state?

As the pontiff argues, the historical influence of the church on European civilisation cannot be underestimated. But there's a reason why his holiness was not invited to the party he's now trying to gate crash.

Eurosceptics often complain that the whole European project suffers from a crisis of legitimacy. They balk at the idea that unelected Eurocrats can dictate certain aspects of our lives for us. But, even the European Commission, the EU's executive arm, imperfect as it may be, is ultimately accountable to elected leaders.

We are also, for various reasons, apparently living through a crisis of democracy at all levels. But, with electoral participation usually over the halfway mark, the status of democracy in Europe appears a damn sight healthier than the embattled church.

The state of the church in Europe today is as frail as the ailing pontiff's health. Regardless of denomination or country, the proportion of regular church goers is plummeting to the low single digits. In fact, ever since the Enlightenment formalised the split between church and state, the institutional status of religion has been in constant decline.

The church may have represented a cornerstone of Europe's past but, for better or worse, it holds little sway in the continent's present. And so, should a charter that deals with the future and one that may form the basis of the hotly debated ‘European Constitution' devote so much attention to the past?

If it does, why stop at the church? Much of our modern ideology is underpinned in Ancient Greek philosophy. So let's give them a mention too, after all they gave us the word ‘democracy' – that elusive state towards which we all strive.

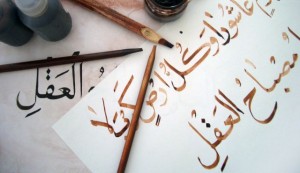

The ascendancy of reason over superstition that started in the Renaissance is partly thanks to the Arabs and Muslims, who gave modern Europe its scientific, medical and mathematical basis. Hell, they even preserved and interpreted the Greek masters who inspired Europe to build its democracies. Perhaps Mr d'Estaing, despite his obvious aversion to Turkish entry to the EU, should give the much-maligned Muslims a mention in his convention.

Finally, I have a personal interest in having the charter mention the Ancient Egyptians for giving us the first civilisation, without which none of what is being attempted today would have been possible.

Is the burden of history getting a bit much for you?

Well, the burden of the present is no less significant. The days of referring to Europe as Christendom are long gone. Modern day Europe is a secular, multi-faith entity. More importantly, whether or not you lament the death of spirituality and the emergence of the dogma of consumerism, most people today are ‘undecided', ‘non-practising', ‘atheists' or ‘agnostic'. Religion may still be important to some people, but that is largely a private matter. Practising believers are in the minority, whether they be Catholic, Protestant, Muslim or Jew.

Europe's higher ideals and morality may be founded on religion, but it is a more universal form of religion, one that is common to most of the major faiths, and not the exclusive domain of the church.

The EU is suffering from a major image problem. Millions of European citizens associate it with the grey machinations of bureaucracy in far-off Brussels. Giscard and his crew desperately need to overhaul the EU and make the project more relevant and inspiring for the average citizen. But, one wonders if the Convention were to bring the Vatican onboard, whether they would also be assigning the Union to the annals of history.