The truth about Islamic reformations

By Khaled Diab

Islam needs a reformation for Muslim societies to develop and prosper, is one of those rare convictions shared by both Islamophiles and Islamophobes. Tunisia has done just that: radically reformed its brand of Islam and established a vibrant democracy to boot, yet prosperity eludes it. Why?

Photo: ©Khaled Diab

Thursday 18 January 2018

Seven years after the downfall of Tunisia's long-time dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisians have been out on the streets once again, in one of the most sustained waves of protest since the 2010/11 revolution.

Paraphrasing the calls demanding the removal of the president in January 2011, the demonstrators of January 2018 have been chanting: “The people want to topple the budget.”

The 2018 budget fuelling public anger led to spikes in value-added tax and social security contributions and a planned slashing of the budget deficit demanded by the IMF, which will cause Tunisia's poor continued pain. In a bid to counter public anger, the government of President Beji Caid Essebsi unveiled plans to reform medical care, housing and increase aid to the poor.

But the upheavals in Tunisia should, by right, not be happening, according to the received wisdom. Public intellectuals and media celebrities in the West, as well as many Muslim reformers, have been informing us for many years that Islam desperately needs a reformation. This would enable Muslims to shake off benighted Islamic dogma and embrace democracy, heralding an era of freedom and prosperity.

For example, more than a dozen years ago, Thomas Friedman, the guru of hollow, superficial punditry, urged Muslims to embark on a Lutheranesque Reformation to create “an Islam different from the lifeless, anti-modern, anti-Western fundamentalism being imposed in Iran and propagated by the Saudi Wahhabi clerics” – never mind that Martin Luther was a fundamentalist zealot and his reformation plunged Europe into generations of war and conflict.

Friedman also believed that America could expedite this reform process towards an Islamic enlightenment by bombing Iraq and resurrecting it as a beacon of freedom, free markets and democracy – and we all saw how well that worked out.

Although American ordnance and weapons, unsurprisingly, set Iraq back generations, some countries have found their own way towards democracy and a reformed Islam without the need for trillion-dollar American wars.

Tunisia has, over the past seven years, built up a vibrant and functioning democracy, which has not only avoided the nightmare counter-revolutions and wars which have consumed other countries in the region whose people dared to dream of a better tomorrow, but it also guarantees an impressive range of fundamental freedoms for Tunisian citizens.

Moreover, Tunisia boasts more female representatives than the United States: almost a third of seats in Tunisia's parliament is held by women, compared with under a fifth in the American Congress. In addition, Tunisia possesses an essential plank of social democracy which has been almost completely dismantled in America: a vibrant trade unions movement.

As for reinventing Islam, Tunisia has been doing that for the past century and a half, which has led to a distinctly Tunisian brand of the religion. In the 19th century, numerous Tunisian intellectuals and activists sought ways to reconcile their faith with modernity and science. In the 1950s, the government led by liberation leader Habib Bourguiba secularised the country and introduced a radical reformist personal status law which equalised the relationship between men and women and banned polygamy.

Fears that reforms would be slowed or reversed by the revolution have proved unfounded. Rather than Islamise society, Tunisian society has secularised the country's main Islamic party Ennahdha, which has gone from an overtly Islamist platform to reinvent itself as a party of ‘Muslim democrats'.

In recent months, Tunisia has rolled out an impressive package of reforms which will have profound implications on the local brand of Islam, and perhaps Islam in other parts of the Muslim world.

Tunisia's parliament pushed through landmark legislation to outlaw all forms of violence against women, from street harassment to domestic violence, as well as the scrapping of the controversial practice of allowing a rapist to escape punishment by marrying his victim.

In addition, the government has removed the bureaucratic hurdle that prevented Muslim women from marrying outside their religion. Most ambitiously of all, Tunisia is pursuing legislation that will grant women equal inheritance rights to men, which has provoked the ire of the conservative Muslim establishment elsewhere, including Sunni Islam's leading institution, Al Azhar.

Despite this impressive political, social, cultural and religious progress, Tunisia's economic fortunes have not kept pace, the treasure at the end of Friedman's freedom rainbow has failed to materialise. The economy still grows, but more sluggishly than before, while inflation and unemployment remain high.

So how come Tunisia has not been able to cash in on its reforms?

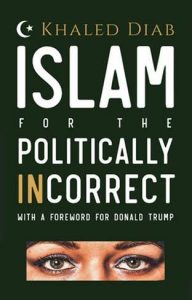

In my new book, Islam for the Politically Incorrect, I offer an explanation for this apparent paradox. At one level, this is because reformations do not lead to socio-economic development but are, instead, the product of it.

In addition, religious, social and political reforms are what you might call the software of development, and Tunisia has given itself a major upgrade in these areas. However, the software is useless without the appropriate hardware. What use is having the operating system for a supercomputer when you only possess a punch-card mainframe to run it on?

And the economic hardware requirements today are exponentially higher than they were when Europe had its Reformation, Counter-Reformation and Enlightenment. Whereas back then, when Christendom was pirating the latest software from Islamic culture and competing to smash Islam's monopoly on global trade, the hardware requirements, in terms of resources and infrastructure, were relatively modest, today that is no longer the case.

As a small illustration, the OECD group of industrialised states spent, in 2009, $874 billion on research and development. To put that in context, the gross domestic product of Egypt, the most populous Arab country, was $336 billion in 2016, while Tunisia's is a mere $42 billion, less than half Google's annual revenue.

And that is just annual spending on R&D. That does not include the huge amounts the West and other advanced economies invest in education, not to mention the generations-long construction of legacy intellectual and technological capital.

Gaining Tunisia and the wider region, not to mention other poorer countries, access to the phenomenal levels of necessary resources will require both a pooling of regional wealth as well as radical policies to address global interstate inequalities. In the absence of enlightened mechanisms for wealth and knowledge sharing and redistribution, we are likely to see the burgeoning of regional and global conflicts that may make the current upheavals seem minor in comparison.

Of course, whether or not democratisation and enlightenment lead to prosperity, they are noble goals to pursue in their own right for the sake of freedom, fairness, justice, knowledge and human dignity. However, if they do not deliver on the economic bottomline, these advances are fragile and can quickly be shattered by popular discontent and populist authoritarian forces. If human enlightenment is to survive, let alone thrive, we need global solutions, not local illusions.