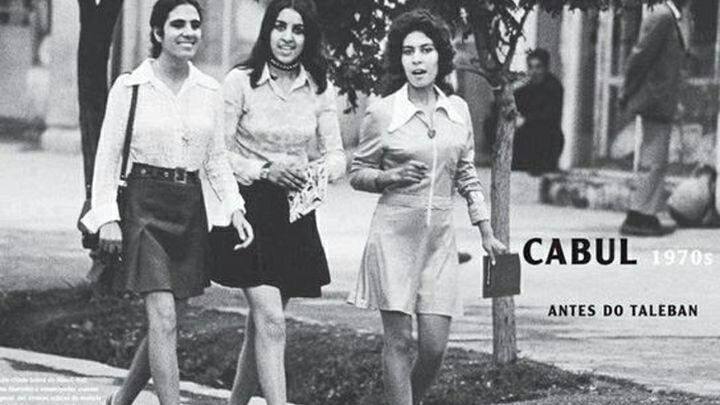

Muslim women in short skirts and the Tunisia paradox

By Khaled Diab

Bombing Afghanistan will not bring back women in short skirts, rather it will only empower men in short skirts (beards and long trousers). The path to gender equality lies in internal reform, as Tunisia demonstrates.

Tuesday 5 September 2017

While not quite the face that launched a thousand ships, a photo of Afghan women in miniskirts in 1970s Kabul helped convince Donald Trump to commit more troops to Afghanistan rather than to pull out of the unwinnable war, according to information revealed by The Washington Post.

National security adviser HR McMaster had wanted to show Trump that “Western norms had existed there before and could return,” according to the report. That the national security adviser would choose this means of persuasion and that the president would be convinced by it betray a profound misunderstanding of Muslim women, their status and how to liberate them.

Bombing Afghanistan will not bring back women in short skirts, rather it will only empower men in short skirts (and long trousers), i.e. the Taliban. Regardless of what an invader professes to offer, people tend not to take kindly to being maimed, killed and occupied for their ‘liberty’, which strengthens the hand of those fighting the occupier.

More importantly, Muslim women do not need American (mostly) men with guns to empower them. The reverse is usually true, as reflected by the worsening status of Iraqi women since the US invasion in 2003, which occurred long before ISIS came on the scene. In contrast, the most successful experiments in female emancipation in the Muslim world have been organic and internal, drawing inspiration, not imposition, from the West.

A case in point is Tunisia. In the cosmopolitan capital Tunis, where I live, you do not need to consult grainy black-and-white photos, women dressed in short skirts, shorts, sleeveless tops and tight jeans abound on the streets, while many of the beaches are filled with local women sunbathing or swimming in bikinis, who often share the water with their burkini-clad conservative compatriots – even if they do often view one another with mutual contempt.

Of course, clothes are only fabric-deep and are an unreliable bellwethers of a woman’s religious beliefs and of how empowered she is, as I highlight in my new book Islam for the Politically Incorrect. There are women who dress in revealing clothes but are religiously conservative and pious, and there are women who wear a hijab but barely practise their faith and are sexually liberal.

What is far more significant is the progress Tunisian women have made. In some respects, they are ahead of many of their western counterparts. For instance, abortion was legalised in Tunisia several years before it was in the United States. Today, almost a third of seats in Tunisia’s parliament is held by women, compared with under a fifth in the American Congress. However, despite being highly educated, Tunisian women make up a far smaller fraction of the labour force than their western peers.

While Tunisian women established an actual feminist movement almost a century ago and it has been two centuries since some Tunisian men started advocating for women’s rights, it was not until their country gained independence that women’s rights began to advance in earnest. Freed of their French overlords, Tunisians were finally liberated from the equating of religious conservatism with authenticity during the struggle for independence and could pursue a progressive programme of reform and modernisation in earnest.

Habib Bourguiba, leader of the liberation movement and the country’s first post-independence president, is often credited with putting in place the enlightened and progressive legal framework which has so benefited Tunisian women in comparison with their Arab neighbours.

But Bourguiba did not emerge in a vacuum, nor did he operate in one, even if he was a dictator. Bourguiba took over the reins of the nationalist movement at a time when women (not to mention women-friendly men) were playing an increasingly prominent role in civil society, journalism, anti-French activity and in demanding gender equality. This long tradition of hard battles and hard-won gains, underpinned by the foresight of the early codification of equality in law, can be seen today.

The received wisdom among many observers was that the revolution of 2010/11 would spell disaster for women’s rights in Tunisia, that dictatorship was the only way to impose modern secular values on a society presumed to be steeped in religion and tradition.

While a significant percentage of Tunisians are, like many Americans, deeply religious and conservative, the country’s founding vision has proven remarkably durable, despite recent economic hardship and the uncertainty of revolution, thanks to the robust activism of Tunisian women and secular forces, as well as to the relatively enlightened pragmatism of the country’s mainstream Islamist party, Ennahdha.

More impressively still, it seems that the cause of gender equality is progressing, rather than regressing – which would appear paradoxical, especially when compared to the much of the wider region. In fact, recent weeks have seen frenzied activity in this regard. Backed by civil society and cross-party support, Tunisia’s parliament pushed through landmark legislation to outlaw all forms of violence against women, from street harassment to domestic violence, as well as the scrapping of the controversial practice of allowing a rapist to escape punishment by marrying his victim.

A couple of weeks later, on Tunisian Women’s Day, President Beji Caed Essibsi unveiled plans to annul an unconstitutional circular or decree barring Muslim women from marrying non-Muslim men and called on the government to review Tunisia’s archaic and unequal Islamic inheritance laws, which grant men double the inheritance of women.

The proposed marriage reform has met with little opposition from mainstream Islamists, even if some conservative men I have encountered have been outraged and baffled by the move. Speaking on a popular FM music channel, Ennahdha’s vice-president and co-founder Abdelfattah Mourou called the question of whom a woman chooses to marry one of “personal choice” – though he did hint that if she wanted to please her God, she would not marry out of the religious fold.

However, the issue of inheritance has proven far more thorny, as anything relating to money tends to be. While men safeguarding male privilege would be unsurprising, many of the staunchest opponents to the proposed inheritance reform are reportedly conservative women. “I have spoken with so many women who feel strongly about this,” Ennahdha’s Mona Ibrahim was quoted as saying.

Secular women feel just as strongly about the issue, albeit from the opposite direction. For instance, a friend, Shiraz, is married to a French man who was obliged to ‘convert’ to marry her, but this is, at the end of the day, a simple procedure that, for the pragmatist, is neither here nor there. In addition,

“What bothers me the most is the question of inheritance. Why should a man get double what a woman gets?” Shiraz asks. “It is just so unfair.” At times the injustice is multiplied, Shiraz points out, in the case of, say, rural women who go to the city to work and send back large chunks of their earnings to their parents who use the money to buy land or build a house. When the parents die, they are entitled to half of what their brothers receive.

The controversy over inheritance has sparked a heated but civil debate in Tunisia, with religious and secular voices falling on both sides of the debate. However, President Essibsi’s proposal has whipped up a storm of protest, as well as a wave of support, for Tunisia and Tunisians across the region, both in the real world and on social media, with one nutty and fanatical Egyptian columnist proposing the Arab world declare a holy war against Tunisia’s ‘apostasy’.

Further illustrating how hell hath no fury like middle-aged conservative men scorned, clerics at Egypt‘s al-Azhar, traditionally considered the highest seat of Sunni learning in the world, expressed the kind of outrage and fury one normally associates with mass murder at how their Tunisian counterparts had broken with orthodoxy, not to mention al-Azhar’s theological hegemony, to back equal inheritance rights.

Tunisia’s Grand Mufti Othman Batikh’s response to the attacks, in contrast, was measured and dignified, pointing out that Islam was not set in stone, and that past interpretations that suited one age needed to be reinterpreted in light of the changing circumstances of another age.

Whether or not the ambitious inheritance reforms, which civil society has been advocating for some years, succeeds is uncertain, but it has opened up a necessary public debate and provided liberals and progressives with much-needed momentum.

Pingback: FAQ ME: Answers that make sense of the Middle East - The Chronikler