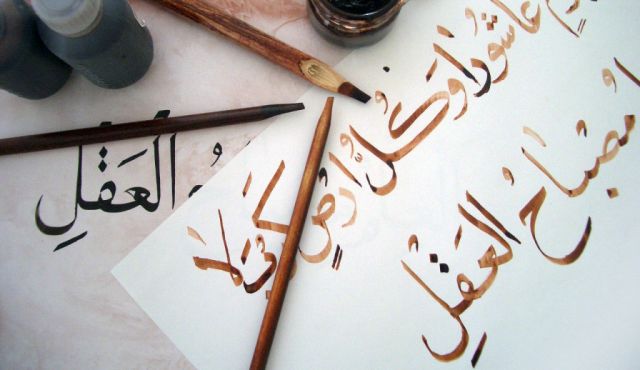

Arabic: The language of confusion?

By Khaled Diab

If an Arab says he'll kill you, don't worry – he wants to buy you dinner. Whether Arabic dialects are a single language is political, not linguistic.

Tuesday 30 December 2014

Earlier this month, the United Nations celebrated Arabic Language Day which got me musing about whether that should be in the singular or take the plural form, Arabic Languages Day.

It is something of a recurring joke among Egyptians who do not speak foreign languages to quip that they speak two languages: Egyptian and Fusha (Modern Standard Arabic).

For language purists and traditionalists, the various forms of colloquial Arabic (amiya or darija) are simply bastardisations of classical Arabic and do not merit much attention.

In fact, it took decades of struggle before Arabic vernaculars became accepted as more than spoken languages. The late colloquial poet Ahmed Fouad Negm – who managed to piss off three Egyptian presidents enough to jail him – did not just shock the establishment with his irreverence, dissent and obscenity but also his insistence on employing Egyptian working class Arabic, rather than the refined poetic language of classical Arabic, in his verse.

But Negm, and other trailblazers before and since, have given amiya authenticity, respectability and, most of all, street cred. And today colloquial Arabic is used regularly on TV, social media and even in literature.

This is just as well. As any frustrated foreign learner of Arabic can tell you, speaking the classical language can make you sound like you've stepped out of a TV period drama about, say, Saladin, or give people the impression that you're a newscaster – in other words, it's just not natural.

Not only does standard Arabic not feel natural to most Arabs, the differences between it and some vernaculars is so great that schoolchildren sometimes feel they are learning a second language, though not quite a foreign language.

But when it comes to the dozens of Arabic dialects, some would surely qualify as a foreign language. If the definition of a language is that its speakers can understand each other, then Arabic often fails this test, since some of its dialects are mutually unintelligible.

The decision to classify all these dialects as being the same language is both political and historical. Arabic is at the core of modern Arab identity and so promoting the idea of common nationhood has required the glossing over of these linguistic differences. Such apparent linguistic unity also encouraged the illusion that Arab unity was natural and inevitable, which meant that pan-Arabism rested more on sloganeering than on concrete efforts to bridge the huge cultural, economic, social and political differences in the region.

In addition, Arabic remains the only generally accepted liturgical language for Islam – which used to confound me as a child when I came across Pakistani and Indian friends in London who knew the Quran by heart but didn't comprehend a word they recited.

Speakers of dialects from the Arab Mashriq (East) cannot generally understand people from the Arab Maghreb (West). Try as I may, I have never managed to decipher Algerian, and Moroccan is a serious challenge, even after encountering many Moroccans in Belgium. While travelling around Morocco, I was amused by the fact that it was sometimes easier to communicate with locals in French than in Arabic, since many were not well-versed in standard Arabic.

There is a certain level of mutual unintelligibility even between dialects in close geographical proximity. Even among mutually intelligible and relatively similar dialects, like Egyptian and Palestinian, there is plenty of room for confusion.

When I first moved here, to Jerusalem, I was surprised to discover just how different the words in Egyptian and Palestinian were for many basic items. These include bread (eish/khobez), shoes (gazma/kondara) and slippers (shebsheb/babouj). Many basic phrases also differ significantly: How are you? (ezayak/kefak?), good (kewayis/meneeh), What's this? (Eh dah/Shoo hada?).

Many common verbs vary too: look (bos/itala'), run (igree/orkod), lift (sheel/irfa'a), hug (uhdon/a'ebot), etc. This is why I sometimes feel sorry for my son. At five, he is grappling with four languages (Arabic, Dutch, English and French), but the Arabic component must feel like more than one language to him.

Sometimes, and this is where the real fun begins, the same word exists but it can have quite a different meaning, leading to much mirth or confusion or even insult.

Palestinians have repeatedly described a person to me as “naseh”. To my Egyptian ears, this means smart, clever or even a wiseass. But here it means chubby. Some Palestinians have on occasion told me that I look “da'afan” which to my ears sounds like “weak” or “under the weather,” but to them it means “you've lost weight.”

Speaking of health, many Palestinians bid each other farewell by saying: “Ye'tek el-afiya” which literally means “May you be given rigour.” In Egypt, we only say that to sick people and so, in my early days here, I wondered why some people thought I was unwell.

Sometimes these dialectical differences can cause bewilderment. While “mabsout” in Egypt and some other countries means happy or in a good mood, in Iraq, it means to be “beaten up.” A friend relates an anecdote in which an ICRC worker visiting Iraqi prisoners asked them whether they were “mabsouteen” and they were utterly confused by the question.

Speaking of violence. A German friend of mine who went out to dinner with a Tunisian was told in no uncertain terms that her date would “khalas aleki.” In the Egyptian dialect she knew, it meant “finish her off.” Confused, she asked him why he wanted to kill her, to which he explained that, in Tunisia, it means that he was going to pick up the tab.

Sometimes, Arabs visiting other Arab countries can unintentionally cause insult. While in many dialects “marra” is just the normal way of referring to a woman, in Egypt, it is derogatory and verges on calling her a “slut.”

Even respectful terms like teacher (me'allem, for a man, or me'allema, for a woman) mean something different in Egypt. For Egyptians, a me'allem is the boss of a gang or a group of manual workers or craftsmen, while a me'allema is a head belly-dancer.

With all these mind-boggling variations, whether or not Arabic qualifies as a single language or many languages is really in the eyes, and ears, of the beholder.

If the idea of Arab unity is to have any kind of future, these linguistic differences, not to mention socio-economic and political ones, need to be recognised and accommodated. Arabs need not speak with a single voice, but need to find harmony among their chorus of divergent voices.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is an extended version of an article which first appeared in Haaretz on 18 December 2014.

Pingback: Remembering the other right of return - The Chronikler

As a liberal African Arab, I agreed with most of your political views and comments. However, your views hear under “Language of Confusion” look odd and pointless. The differences found between Arabic dialects is true about all world languages, but yet we talk about francophones or Anglophones as linguistic groups. I live in GCC region and have work colleagues and friends from Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Palestine and Lebanon. We easily learned to communicate in Arabic despite some difficulties felt in the beginning. Moreover, classic Arabic is the same in all Mashreq and Maghreb countries. Books, newspapers and all printed materials are exchangeable between these countries.

Pan-Arabism failed for many reasons, but not for the lack of linguistic homogeneity. Arabic was always seen as a unifying element, and not the contrary. May be, it was over stressed as a corner stone in building Arab unity without giving due regard to the many barriers and contradictions between Arabic speaking nations. A good reason for the failure was the fact that “unity” of Arab countries was never adopted or sought as a way for development or modernity except by few ideological parties and intellectuals.

When I found at the bottom of the page that the article had first appeared in Haaretz, I felt it was written to appeal to the Israeli readers who should cheer on discovering that their enemy is not a unified one bloc, but as diverse and alien as other regions. I see no other reason for a good commentator to suddenly write so unconvincingly in contrast to his other brilliant articles.

What you define as a single language is almost always a political decision. Of course, this is not the only reason pan-Arabism failed. But the illusion that shared a language somehow made Arabs a natural single nation led to the socio-cultural, political and economic difference the region being swept under the carpet, leaving us with slogans instead of concrete efforts to promote unity amid such diversity.

I go into much more detail about this in an article I wrote for an (Arab) newspaper (my ideas are reached through independent thought and not as a way to pander to a particular audience.

http://www.thenational.ae/the-language-of-the-arabs-has-more-often-divided-than-united

Israeli readers of Haaretz such as I (a Jew) could hardly be generalized as cheering “on discovering that their enemy is not a unified one bloc, etc.” Equating Arab as enemy is largely ignorant and even repulsive.