The caliphate illusion: “Restoring” what never was

By Khaled Diab

The tyranny of Arab secular dictators and destructive Western hegemony combined to enable ISIS to “restore” a brutal caliphate which never existed.

Monday 7 July 2014

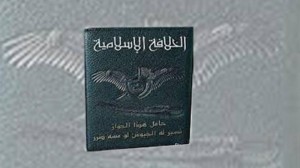

The Islamic State in Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) – or simply, the Islamic State, as it now prefers to be called – is well on the road to achieving its end goal: the restoration of the caliphate in the territory it controls, under the authority of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, an Islamist militant leader since the early days of the American occupation of Iraq.

The concept, which refers to an Islamic state presided over by a leader with both political and religious authority, dates from the various Muslim empires that followed the time of Muhammad. From the seventh century onward, the caliph was, literally, the prophet's “successor.”

The trouble is that the caliphate they seek to establish is ahistorical, to say the least.

For instance, the Abbasid caliphate centred in Baghdad (750-1258), just down the road but centuries away (and ahead) of its backward-looking ISIS counterpart, was an impressively dynamic and diverse empire. In sharp contrast to ISIS's violent puritanism, Abbasid society during its heyday thrived on multiculturalism, science, innovation, learning and culture, including odes to wine and racy homoerotic poetry.

The irreverent court poet of the legendary Caliph Harun al-Rashid (circa 763-809), Abu Nuwas, not only penned odes to wine, but also wrote erotic gay verse that would make a modern imam blush.

With the Bayt al-Hekma at the heart of its scientific establishment, the Abbasid caliphate gave us many sciences with which the modern world would not function, including the bane of every school boy, algebra, devised by Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi. Even the modern scientific method itself was invented in Baghdad by the “first scientist” Ibn al-Haytham, who also made major advances in optics.

With the proliferation of sceptical scholars, even religion did not escape unscathed. For example Abu al-Ala'a Al-Ma'arri was an atheist on a par with anything the modern world can muster. “Do not suppose the statements of the prophets to be true,” he thundered. “The sacred books are only such a set of idle tales as any age could have and indeed did actually produce.”

And he uncharitably divided the world into two: “Those with brains, but no religion, and those with religion, but no brains.”

And it is this tolerance of free thought, not to mention the “decadence” of the caliph's court, which causes puritanical Islamists of the modern-day to harken back to an even earlier era, that of Muhammad and his first “successors” (caliphs).

But the early Rashidun (“rightly guided”) Caliphs bear almost no resemblance to Jihadist mythology. Even Muhammad, the most “rightly guided” Islamic figure, did not establish an Islamic state, at least not in the modern sense of the word. For example, the Constitution of Medina drafted by the prophet stipulates that Muslims, Jews, Christians and even pagans all have equal political and cultural rights. This is a far cry from ISIS's attitudes towards even fellow Sunni Muslims who do not practise its brand of Islam, let alone Shi'a, Christians or other minorities.

More crucially, the caliphates in the early centuries of Islam were forward-looking and future-oriented, whereas today's wannabe caliphates are stuck in a past that never was.

How did this ideological fallacy of the Islamist caliphate come about?

To understand the how and why, we must rewind to the 19th century. Back then, Arab intellectuals and nationalist wishing to shake off the yoke of Ottoman dominance were great admirers of Western societies and saw in them, in the words of Egyptian moderniser and reformer Muhammad Abdu, “Islam without Muslims”, hinting at the more secular reality of the Islamic “golden age”. Another Egyptian moderniser, Rifa'a al-Tahtawi, urged his fellow citizens to “understand what the modern world is”.

Interestingly, many of these reformers were educated as Islamic scholars but were enamored of modern European secularism and enlightenment principles. Taha Hussein, a 20th-century literary and intellectual trailblazer, started life at Al Azhar, the top institute of Islamic learning, but soon abandoned his faith.

Many Arab nationalists not only admired Europe and America but believed Western pledges to back their independence from the Ottoman empire, the “sick man of Europe”.

The first reality check came following the Ottoman defeat in World War I when, instead of granting Arabs independence, Britain and France carved up the Middle East between them, as if the region's people were the spoils of war.

Disappointed by the old powers, Arabs still held out hope that America, which had not yet entered Middle Eastern politics in earnest, would live up to its self-image as the “good guy” and deliver on its commitment to “self-determination”, as first articulated by Woodrow Wilson.

But following World War II, America filled the void left by France and Britain by emulating its imperial predecessors, though it steered clear of direct rule. Instead, it propped up unpopular dictators and monarchs as long as they were “our son of a bitch”, in the phrase reportedly coined by Franklin D Roosevelt. This principle was eloquently illustrated in the same person, Saddam Hussein, who was an ally against Iran when he was committing his worst atrocities, such as the al-Anfal genocidal campaign and the Halabja chemical attack of the 1980s.

This resulted in a deep distrust of Western democratic rhetoric, and even tainted by association the very notion of democracy in the minds of some.

Then there was the domestic factor. Like in so many post-colonial contexts, the nation's liberators became its oppressors. Rather than dismantling the Ottoman and European instruments of imperial oppression, many of the region's leaders happily embraced and added to this repressive machinery.

The failure of revolutionary pan-Arabism to deliver its utopian vision of renaissance, unity, prosperity, freedom and dignity led to a disillusionment with that model of secularism. While the corruption and subservience to the West of the conservative, oil-rich monarchs turned many against the traditional deferential model of Islam.

This multilayered failure, as well as the brutal suppression of the secular opposition and moderate Islamists, led to the emergence of a radical, nihilistic fundamentalism which posited that contemporary Arab society had returned to the pre-Islamic “Jahiliyyah” (“Age of Ignorance”).

The only way to “correct” this was to declare jihad not only against foreign “unbelievers” but against Arab society itself in order to create a pure Islamic state that has only ever existed in the imaginations of modern Islamic extremists. These Islamists misdiagnose the weakness and underdevelopment of contemporary Arab society as stemming from its deviation from “pure” Islamic morality, as if the proper length of a beard and praying five times a day were a substitute for science and education, or could counterbalance global inequalities.

The wholesale destruction of Iraq's political, social and economic infrastructure triggered by the US invasion created a power vacuum for these “takfiri” groups – first al-Qaeda and then the more radical ISIS – to make major advances.

In an interesting historical parallel, the man considered “Sheikh al-Islam” by many radical Salafists today, Ibn Taymiyyah, also emerged during a period of mass destruction and traumatic upheaval, the Mongol invasions. He declared jihad against the invaders and led the resistance in Damascus.

Despite ISIS's successes on the battlefield, there is little appetite or support among the local populations for their harsh strictures, a dact reflected by the 500,000 terrified citizens who fled Mosul. Even in the more moderate model espoused by the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist dream of transnational theocratic rule appeals to a dwindling number of Arabs. Only last week, Moroccan women showed their contempt for the conservative prime minister, Abdelilah Benkirane, by converging on Parliament armed with frying pans after he'd argued that women should stay in the home.

Rather than a caliphate presided over by arbitrarily appointed caliphs, subjected to a rigid interpretation of Shariah law, millions of Arabs strive simply for peace, stability, dignity, prosperity and democracy. Three turbulent years after the Arab revolutions, people still entertain the modest dream of one day having their fair share of “bread, freedom, social justice,” as the Tahrir Square slogan put it.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is the extended version of an article which first appeared in the New York Times on 2 July 2014.

Pingback: FAQ ME: Answers that make sense of the Middle East - The Chronikler

Pingback: El ‘califato’ se presenta en sociedad – Recortes de Oriente Medio

Pingback: El “califato” se presenta en sociedad | Recortes de Oriente Medio