“Never again or forever more?” asks veteran war reporter

I was almost certain that the Russian invasion of Ukraine would not take place. I was at an utter loss as to what the Kremlin could hope to achieve with such a clearly insane military venture. Staring at the endlessly scrolling explosions of narcissistic hatred on social media, I wonder what I, who once believed in the ‘never again' mantra, still have to offer in this post-fact age of sabotaged attention spans.

Thursday 3 March 2022

I've seen this so many times, always hoping and praying never to see it again. Time and time again, I have been taken in by the hollow Never Again mantra.

I grew up in a country fated to be torn asunder by a series of horrific wars after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The first wars on European soil after World War II, if I may correct a long line of journalists and analysts with evidently very limited historical memories.

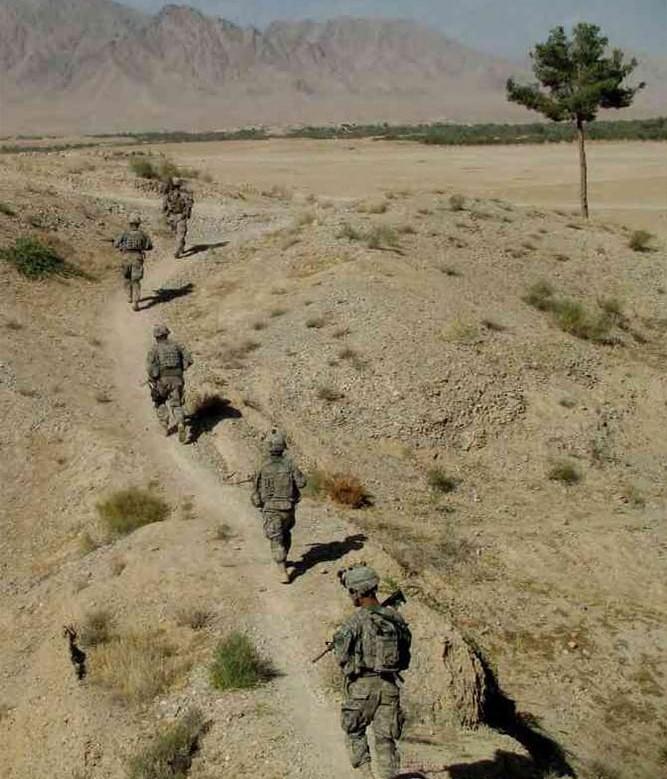

Perhaps it was growing up in this kind of environment that made me follow wars around the globe for 20 years, starting with Kosovo. I was too young to cover the wars in Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. But after Kosovo in 1999, I went on to report from Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gaza, Darfur, Lebanon, Pakistan, South Sudan, Kurdistan, Syria and Libya. Throughout my war-chasing years, I strived to pay particular attention to the fate of refugees and other people whose lives have been completely blown apart by senseless violence.

My two decades as a war reporter taught me to always expect the darkest scenario with very little room for hope. A severe overload of human suffering was the main reason I gradually lost my mettle and decided to retire from (anti-)war journalism. Actually, that is not entirely true. After I stopped following war around the globe, I began reporting on the consequences of climate change, which I believe to be the most important frontline in human history.

For the last few weeks before Vladimir Putin decided to attack Ukraine, most of the prominent Western media were filled with stories about the inevitability of war – so much so that the actual invasion seemed very much like wish fulfilment, or at least a self-fulfilling prophecy. Yet in spite of that I was almost certain that the Russian invasion would not take place. I was at an utter loss as to what the Kremlin could hope to achieve with such a clearly insane military venture.

And then images of bloodshed started coming in from Ukraine, the exact same images of wanton slaughter that have been following me all my life. Apartment buildings eviscerated by homing missiles. Savage detonations. Tanks deliberately trampling over private vehicles. Endless lines of refugees. Hatred. Fear. All-pervasive war propaganda. And presiding over it all, the mounting outbursts of the most heinous nationalist sentiment.

Along with these images came the inevitable conflict on social media: a veritable flood of madness, lies, pathological conspiracy theories and, above all, opinions. Immovable jingoistic opinions based on little else than a total lack of empathy. But today, opinion is king, and semi-literate sentiment reigns supreme.

As a veteran journalist, I find it very hard to come to grips with the idea that it is the very same flood of madness that is now upending my profession. True, a part of the blame can be ascribed to our – the journalists' – complacency. But the fact remains that we have been all but stripped of the privilege of interpretation. In a sense, the rise of the (anti-)social media networks is turning us into intellectual expatriates.

This bizarre turn of events fills me with overwhelming frustration and a sense of increasingly unbearable impotence. I believe the way our algorithm-driven reflexes are now trouncing reflection is one of the key drivers of modern conflicts. The public seems to have undergone a seismic shift. Staring at the endlessly scrolling explosions of narcissistic hatred, I can only wonder what I still have to offer in this post-fact age of sabotaged attention spans.

As to the particular nature of the war at hand, I have very little to say. I believe the only ones likely to issue credible verdicts on such matters are the people who experienced the particular conflict first-hand.

But since I do know something about bombardment, wholesale destruction and decomposing corpses of children, please allow me to say this. We should all be reeling at the thought that, despite all history's lessons, the war path has been taken again. And we should all be daily scouring our souls for the tiniest inclination to defend this war, to justify it – least of all snugly from the couch.

For a long time I believed that sound and dedicated fieldwork can help change the world for the better. This belief used to be my driving force. And on a few infinitely precious occasions, I have managed to effect positive change – though always on the micro-level, while covering human-interest stories in thoroughly devastated lands. Yet the big picture always remained the same.

Many of the wars I've covered over the past two decades have now become permanent: Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, Gaza, the Congo, … The countless refugees these conflicts produced are now seen and increasingly treated as nuclear waste by the racist policymakers all over Europe and the United States. The open and free society supposed to spring up all over the post-communist Europe has long been shelved in favour of the continent's new bout with totalitarianism.

“History is a nightmare from which I'm trying to awake,” James Joyce once remarked. Unfortunately, this notion doesn't seem to be one that is widely shared. Historical memory now seems no more potent a force as last year's snow. I fear the process may be irreversible.

What is certain is that the ongoing conflict in Ukraine will strengthen authoritarian forces everywhere. And that with each passing day, Kiev is beginning to look more like Sarajevo.

Never Again = Evermore.