Podcast: Palestine’s political poster girls

By Khaled Diab

The changing depiction of women in Palestinian political art reflects the shifting perceptions of their role and position in society.

Tuesday 26 January 2016

The word ‘hermit' usually evokes images of men with overgrown beards living in a cave, up a hill or battling spiritual demons in the desert.

But in hermetically sealed, overcrowded and ultraconservative Gaza, the allure of ascetic isolation stretches to the young and artistic woman. In a territory, where the ruins outnumber the intact buildings, where many families live 10 to a room or out in the open, being able to withdraw within, into your own private shell, can feel like a luxury.

“An artist without sufficient liberty is not able to practise her art,” Nidaa Badwan tells me. “My room was the only place in Gaza where I could practise my art.”

Living under the twin confinements of the Israeli blockade and bombings, as well as Islamist rule, which saw Hamas's morality police arrest Badwan for an outdoor performance she once gave, the young artist, 28, decided on the path of self-imposed isolation.

Hidden away inside her creative solitary confinement cell, measuring barely 10 square metres, Badwan creates art. She takes selfies that resemble classical portraits, in their rich compositions of colour and texture.

“I focused on the expressions of the body and it's language,” Badwan explains. “I tried to create homogeneous communication and dialogue between me, my ideas, my body movement, and all of the elements and colours of the photography.”

The results are eye-catching. One photo, or portrait, shows Nidaa in tight black leggings doing a faux ballet move in a dimly lit studio. The same leggings feature in another image of her sitting on an improvised swing made out of an old tyre suspended between two ladders, looking defiantly, even regally, to one side, while she buttons up her shirt. Another image portrays her looking into a pocket mirror while applying rouge to her blood-red lips. Some images are of the artist-at-work variety, while others show Badwan's dreams of different professions she'd like to do.

These and other portraits featured in Badwan's first exhibition in 2015, ‘100 Days of Solitude, which met with critical acclaim. Nidaa explained to me that, in her work, she introduces a different, alternative image of Palestinian and Gazan women but that she wasn't out explicitly to challenge stereotypes. “I simply expressed myself through my art,” she stresses.

Nevertheless, this private self-expression is subversive. Outside the four walls of Badwan's studio a very different reality exists. Strict rules dictate what a “good” Palestinian woman should look like and how they should be represented. “Society does not see women, imagine what they think,” observes Nidaa.

This was driven home to me during an encounter with a group of young female and male writers in Gaza city. Our conversation shifted to how the hijab is often misrepresented in the West as solely a tool of female subjugation. One of the young men in the group provocatively asked me my personal attitude towards the headscarf. Even my diplomatic answer, that I did not approve of it but that I respect women who don it voluntarily, elicited a storm of outrage, among the women more than the men.

Although many women who wear the hijab out of conviction see at as empowering, this is not how the Islamist patriarchy regard it. I was reminded of this sitting at the front of the distinctive green-and-white buses which serve the Palestinian neighbourhoods of East Jerusalem. I was unsettled by faceless twin sisters who stood side by side on the glass panel behind the driver and stared at me eyelessly.

These poster girls for the hijab advise our “Muslim sisters” on how to wear the Islamic headdress and clothes “correctly” in order to be “decent believers”. Not only does this poster, likely produced by a committee of conservative men, presume to tell women what they should wear, it depicts them as minions without faces. Though the faceless caricature is probably supposed to illustrate piety and modesty, its underlying message is that women should be invisible, neither heard nor seen, except discreetly and demurely.

But this has not always been the case. Despite the Islamist preference for feminine coyness, defiant women have long been a staple of Palestinian political art, especially on the left.

The poster girl of that muscular defiance has to be Leila Khaled, the first woman ever to hijack an aircraft, in 1969, which was heading from Rome to Athens. One iconic image captures her staring dreamily, while holding an AK-47 and wearing a ring made of a bullet and a grenade pin.

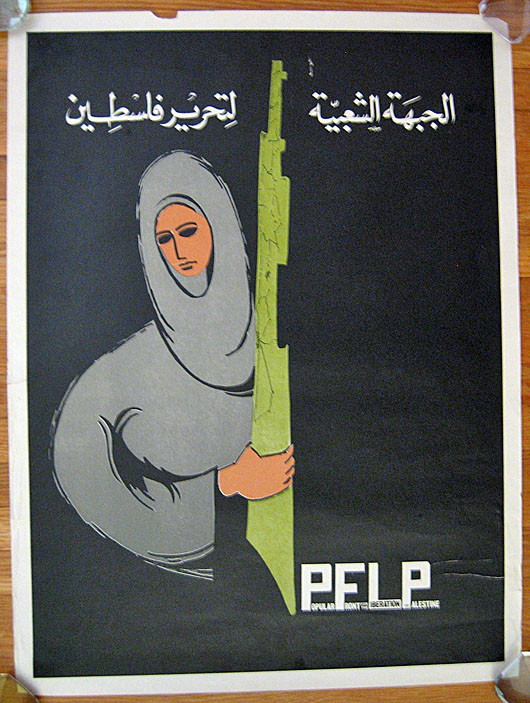

Khaled was a member of the Marxist-Leninist Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which like much of the Palestinian secular left, saw the empowerment of women as a crucial prerequisite for national salvation and justice.

For a time, in the 1960s and 1970s, when Palestinians finally took their cause into their own hands, there was a sense, in the minds of the revolutionaries, that the sky was the limit for Palestinian women.

Nothing reflects that better than the political iconography of the time. Women were depicted as powerful warriors at the forefront of the Palestinian cause. The graphical ground shifted.

Interestingly, a PFLP poster from 1968, designed by revolutionary novelist Ghassan Kanafani, features only a woman carrying a rifle, with no man in sight. A year later, another poster depicts only a horse with a woman alongside it firing a bazooka.

The subliminal message of this period seems to be that the men failed to liberate the Palestinians, so now it was the women's turn. This was almost explicitly spelt out in a poster from 1970 which, in calling for “revolution until victory”, only featured a single woman with a rifle in different poses.

As the Palestinians shifted away from armed struggle and towards non-violent resistance, the prominence of women only grew, despite the slowly rising tide of political Islam. Posters produced during the first intifada often featured figures who were androgynous, and a few were dedicated solely to women, such as one which informs us of how Palestinian women were on the frontlines of the intifada.

“It is going to be very difficult to send these women back to the kitchen or to relegate them to the class of second-rate citizens,” Hanan Ashrawi, the prominent activist, academic and politician who made her name during that uprising.

Despite the massive gains by Islamists and conservatives, the subversive, female-centric art of the late 1960s and 1970s is making a comeback – as if to say to them, “Look, your misogyny and religiosity has also failed to liberate us.”

A new poster, produced during the current upheavals, features a drawing of a woman with her hair and face covered up. But this is not for religious reasons, as reflected in the Palestinian kefeya doing the covering. It is to conceal her identity, for she is an intifadista, as conveyed by the slingshot, Molotov cocktail, knife, rocks and rose in her satchel.

This provoked a backlash from conservatives, who posted hundreds of misogynistic comments on social media bizarrely and surreally protesting the tight clothes used in the image, and demanding that fathers and brothers should keep their womenfolk away from protests and clashes.

But Hanan Ashrawi's political heirs, a new generation of young and determined women, are refusing to be cowed, and are determined to take on both the occupation and the patriarchy. Nidaa Badwan is doing it by carving out her own private-public artistic protest space. Other women are claiming and reclaiming public spaces.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This report was first broadcast on the BBC World Service's The Cultural Frontline on January 2016.

Interesting piece Khaled. Pity it sometimes takes war and violence to liberate women. It’s not a Muslim exclusive. Just look at the transformation of western societies after WWII, where women were essential to the ‘war effort’. Sure many women returned to the kitchens and child-rearing as before, but the tide had definitely changed for good (and for the good)!

Indeed. If it weren’t for the cumulative effect of WWI and WII, and the wars’ destruction of previous certainties, perhaps Western women would be in a considerably weaker position today.