Charlie Hebdo and Islam’s freedom of expression… and insult

By Khaled Diab

Muhammad's self-appointed defenders take offence on his behalf, but the prophet would've tolerated Charlie Hebdo and condemned the savage murders.

Tuesday 20 January 2015

After the brutal assassination of eight of its staff members and two visitors, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo has vowed to continue its trademark irreverence and secular iconoclasm, which critics have accused, in turn, of being Islamophobic, anti-Semitic and anti-Christian.

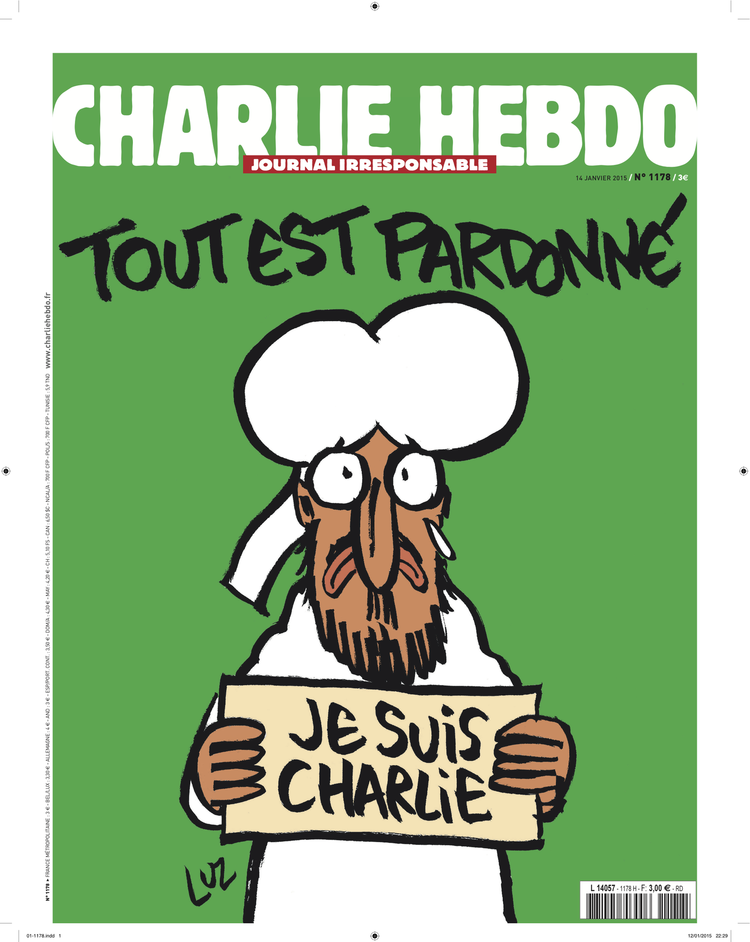

Its first issue since the tragic massacre, which came out on Wednesday 14 January, features a cartoon of a tearful Prophet Muhammad holding a sign which reads “Je suis Charlie”, the famous twitter hashtag. The turbaned figure stands under the slogan “All is forgiven”. If the murderers had hoped to repress representations of their beloved prophet, their actions backfired spectacularly: 5 million copies were circulated of the latest edition, and its cover went viral.

As a staunch advocate of freedom of expression, I believe they have every right to run such a cartoon, even if it has upset the religious sensibilities of some Muslims. Egypt's grand mufti, Shawqi Allam, who blasted the cartoon as racist, while a number of protests took place in various Muslim-majority lands, with the largest occurring in Chechnya.

In France, many Muslims attended the anti-extremism marches held across the country to mourn the deaths at Charlie Hebdo and the Jewish kosher supermarket where four were killed. Further afield, Arabs and Muslims have also held vigils in support of the victims at Charlie Hebdo, and numerous Arab cartoonists have paid tribute to their slain peers with hard-hitting and moving cartoons.

These contrasting reactions got me wondering about a hypothetical question: what would Muhammad make of this? Would the prophet forgive Charlie Hebdo's lampooning of him and his religion, and would he, if he were alive today, tweet his solidarity with the slain cartoonists?

My own reading of history and of Muhammad's life leads me to the conclusion that, were he around in the 21st century, the prophet may not have tweeted “#JeSuisCharlie”, but he would have condemned these savage murders and forgiven whatever insult was directed his way by French satirists.

Some will find my assertion hard to believe, but Muhammad's own actions and convictions back me up on this. Although the prophet's self-appointed contemporary defenders take offence on his behalf and believe they are doing his will when they protest perceived insults or punish those who commit them, this could not be further from the truth.

During the vulnerable early years of Islam, the Islamic prophet endured and tolerated mockery and disdain. Even in victory, Muhammad choose wisely to exercise tolerance. Upon his triumphant return to Mecca, he forgave the inhabitants of the city which had been home to his fiercest enemies, even pardoning Abdullah Ibn Saad who had been a member of his inner circle but later denounced the prophet as a charlatan.

More importantly, the Islam Muhammad preached recognised the pluralistic nature of society and guaranteed freedom of belief. Surat al-Baqara of the Quran reminds Muslims that “there shall be no compulsion in religion”.

Significantly, the constitution Muhammad drew up in Yathrib (Medina) included in its definition of the “Umma” all the oasis's inhabitants, not just Muslims. These included both the “People of the Book”, i.e. Christians and Jews, but also, perhaps surprisingly, pagans, all of whom were granted equal political, cultural and religious rights as Muslims.

And in the early centuries of Islam there was so much freedom of thought and expression that it would put much of the current Muslim world to shame. Although many contemporary Muslims are convinced that ridiculing Islam and rejecting religion are Western innovations, this is more wishful thinking than historical fact.

In Christendom, Muhammad and Islam was derided from a rival religious vantage point: that the prophet of Islam was believed to be the false prophet of a fake religion. He was even condemned to the ninth circle of Dante's inferno where he supposedly stands “rent from the chin to where one breaketh wind”.

In contrast, within the Islamic world itself, Muhammad and Islam were criticised and mocked from a secular, rationalist, anti-religious perspective. One example is the religious sceptic and scholar Ibn al-Rawandi (827-911) who, despite his rejection of religion and Islam, lived a long life in the 8th-9th centuries.

Ibn al-Rawandi, who spent a significant part of his life in Baghdad, believed that the intellect and science supersede all else, that prophets were unnecessary, that religion was irrational, that Islamic tradition was illogical and that miracles were a hoax.

In neighbouring Syria, a few decades later, the Richard Dawkins of the Abbasid era was born. Abu al-Ala' al-Ma'arri (973-1058) was so contemptuous of religion that he divided the world into two types of people: “those with brains, but no religion, and those with religion, but no brains”.

Al-Ma'ari also lived to a ripe age. And rather than being visited by assassins, he attracted many students and engaged with scholars of various persuasions, even when he decided to return to his hometown of Ma'arra to life ascetically in seclusion.

Although this tradition of free thought and scepticism has shrunk over the centuries, it still exists, and even witnessed a resurgence in the 20th century – and included the “dean of Arab literature” Taha Hussein – until the conservative Islamist current started to block it starting from the late 1970s/1980s.

The years since the revolutionary wave erupted in 2011 have seen secularists, sceptics and atheists mounting a comeback. But with some countries equating non-belief to terrorism and arresting atheists, theirs is a risky venture.

But these efforts are essential. Freedom of thought and expression were vital components of Islam's golden age and lifting Arab and Muslim countries out of their current plight will require a return to that era of free inquiry.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is an updated version of an article which first appeared on Al Jazeera on 14 January 2015.