Feminism’s Ancient Egyptian roots

By Khaled Diab

Women's liberation is generally believed to have started in the West but the roots of female emancipation go back millennia, to Ancient Egypt.

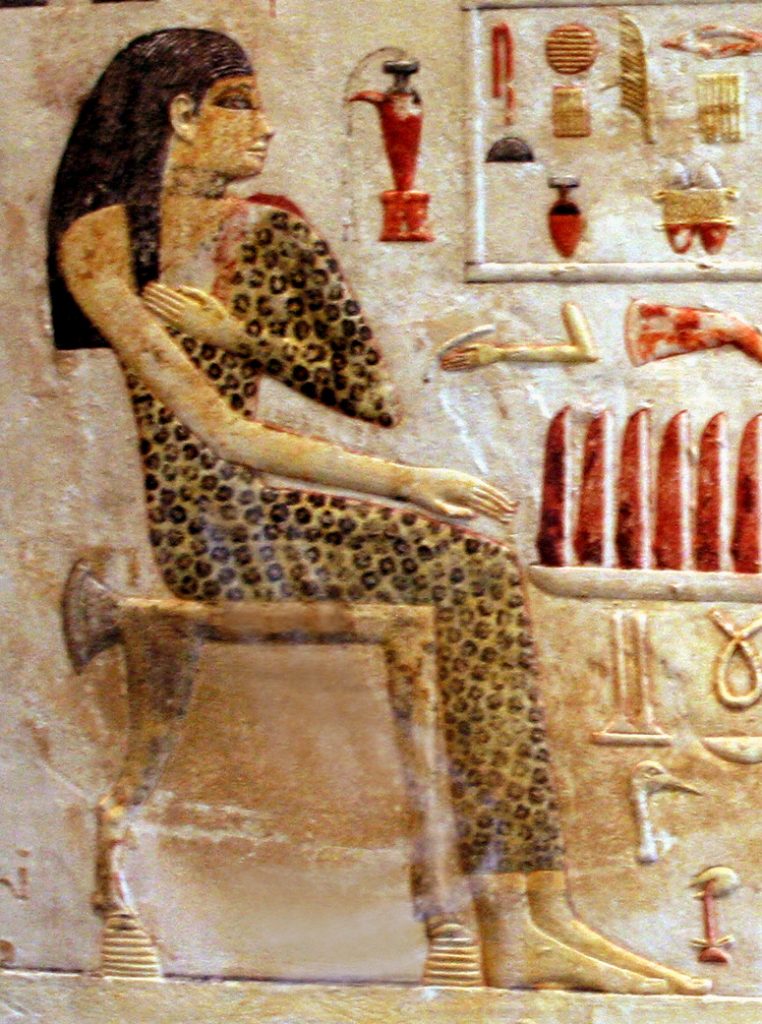

Source: Wikipedia

Wednesday 8 March 2017

Like our Greek cousins across the Mediterranean, Egyptians take outsized pride in their contributions to shaping human civilisation, partly as an antidote to our contemporary state of disarray.

For their part, Europe and America have enjoyed an infatuation with ancient Egyptian civilisation ever since Egypt fell into the European sphere of influence in the 19th century and the architectural splendour of the pharaohs entered popular culture.

But while ancient Greece is widely regarded as the cradle of Western civilisation, ancient Egypt is generally viewed as a distant and remote exotic land which bears little direct relation to contemporary life in the West.

Although ancient Greek philosophy, science and culture have exercised a profound influence on European society since the Renaissance, the influence of Egypt on Western civilisation should not be underestimated, both directly and through its influence on Greece and Rome.

One area where Egypt deserves the title of the cradle of Western civilisation is, perhaps surprisingly, gender equality.

In ancient Greece, women's status bore little resemblance to the contemporary West and was more akin to that in the most conservative Muslim countries today – and, in some ways, was far worse, as Greek women were generally not allowed to own property.

In contrast, though Saudi women are not allowed to drive or go out in public without a guardian, they at least own the lion's share of the kingdom's cash, while in the Gulf as a whole female entrepreneurs manage a whopping $385 billion of wealth.

Unlike in today's West, ancient Greek women were not regarded as citizens, could not vote, were excluded from many public spaces, their names never mentioned in respectable society and they went from their father's guardianship to their husband's.

The relative exception to this was Sparta, where women could own property, be educated and, unlike their shrouded Athenian sisters, were notorious in ancient Greece for their revealing clothes. This prompted the classical misogynist Aristotle to blame the downfall of Sparta on the freedom its women enjoyed. “The want of men was their ruin,” the famed philosopher concluded. However, this greater freedom was not about emancipating women but about empowering society.

Spartan women were not the most empowered in the ancient world. In fact, the relative rights they enjoyed paled into insignificance compared with their Egyptian counterparts. Unlike women almost anywhere in the world until the 20th century, Egyptian women were essentially the legal equals of men for millennia.

“From our earliest preserved records in the Old Kingdom on, the formal legal status of Egyptian women (whether unmarried, married, divorced or widowed) was nearly identical with that of Egyptian men,” writes professor of Egyptology Janet Johnson, whose special interests include ancient Egyptian women.

Under the protective gaze of the goddess Isis, who signified the throne of Egypt, women were entitled to work, own property, go to court, bear witness, serve on a jury and much more. In their private lives, they had the right to choose their partner freely, to marry out of love, to spell out detailed prenuptial agreements to protect them and their children, and to divorce for any reason they wished. In fact, in ancient Egypt, “marriage” was very different to our conceptions of it. “Marriage was not a religious matter in Egypt – no ceremony involving a priest took place – but simply a social convention that required an agreement,”explain Egyptologists Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs.

Given the huge disparity between Egyptian women and their ancient sisters, it is little wonder that Greek tourists expressed dismay when visiting Egypt. “In most of their manners and customs, [Egyptians] exactly reverse the common practice of mankind,” observed the Greek historian Herodotus. “The women attend the markets and trade, while the men sit at home at the loom.”

While Herodotus was wrong about Egyptian men, few of whom practised role reversal, he was right about the women, who could theoretically pursue any profession or career they wished. While Greek women could not practise medicine on pain of death until the advent of Agnodice – who fled Athens to study in Alexandria – female doctors were highly regarded in Egypt. This included a certain Peseshet, who was known as the “overseer of doctors”, and Merit Ptah, who is the first woman ever recorded to have practised medicine, some five millennia ago.

Despite their legal equality, Egyptian women experienced something that would be familiar to their 21st-century counterparts: the glass ceiling. Although they had the legal right to pursue any profession they desired, the upper echelons of Egyptian society were overwhelmingly male. Only a tiny minority of scribes and priests, two of the most respected professions, were women.

The top job of all, that of pharaoh, who was regarded as both human and divine, was mostly off bounds to women, with some notable exceptions throughout Egypt's long history, such as the amazingly accomplished Hatshepsut, Nefertiti and Cleopatra.

We can draw two important lessons from the under-appreciated history of ancient Egyptian woman. Firstly, it can teach the West some humility by showing that it is not the first region in the world to empower women.

Secondly, it can shatter the myth I hear so often from conservatives in Muslim societies and the global South that gender equality are some alien Western import. It can provide Egyptian, Arab and non-Western feminists living in post-colonial societies with alternative inspirations for female empowerment and emancipation, not just to emulate but to surpass.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This article first appeared in Al Jazeera on 3 February 2017.