The concealed links between Israel’s “invisible” citizens

By Khaled Diab

An electoral campaign video targeted at Israel's “invisible” poor unwittingly highlights the long-neglected links between Mizrahi Jews and Arabs.

Friday 6 February 2015

It is a very powerful electoral message. The ad features middle-class Israelis complaining about how tough they have it, while phantom figures around them beg for money, scan their shopping at the supermarket checkout, fill their petrol tanks and clean their homes.

This savvy appeal to the almost 1.7 million “invisible” Israelis who live below the poverty line was not produced by Meretz, Hadash, Labour or any other party on the left of the political spectrum. Surprisingly, the video is the work of Shas, the ultra-Orthodox religious party on the right, most closely associated with Israel's Sephardi and Mizrahi populations.

Analysts suggest that this video is part of a bid to break free of Shas' traditional image of being a religious and ethnic party, and to appeal to a group not explicitly targeted by most of the other parties: Israel's economically marginalised.

“The target audience is obviously broader than anything any ultra-Orthodox party tried before,” Israeli journalist, blogger and analyst Dimi Reider observed. “The ad's inclusivity is particularly startling when one looks at the other parties hoping to swoop in on the social-economic protest vote,” he adds, pointing to how Labour, for example, has fielded only one Mizrahi candidate, who occupies the unelectable 23rd position on the party's list.

Shas's rehabilitated leader Aryeh Deri, who was imprisoned on bribery charges, is credited with this apparent shift to the left, though much of the party does not seem to share his politics, while his leadership is in doubt.

Despite Shas talking the talk of the poor, it is still solidly, like religious parties across the Middle East, walking the walk of the neo-liberal business elites, as reflected in its backing for Likud-led privatisation programmes and austerity measures. “Their campaign is a great one but it is really far away from their politics in the real political world,” notes Mati Shemoelof, a progressive Iraqi-Israeli poet, writer, journalist and activist. “They are part of the problem and not the solution.”

While Shas's campaign video features poor Jews, there is an elephant in the room. Missing from the picture are Palestinian-Israelis, the invisible among the invisible, who make up the bulk of Israel's poor.

The Palestinian citizens of Israel account for 44.5% of Israel's poor, according to a report by Adalah, an NGO that advocates for the rights of Israel's Palestinian minority. Over half of Arab families in Israel are classified as poor, compared to a national average of 20 percent, according to the report. This is a reflection of the fact that Arabs on average earn 32% less than Jews, while the net income of Arab household is less than two-thirds of what their Jewish counterparts take home, the report observes.

Although the Mizrahim are generally somewhat better off than the Arabs of Israel and their relative situation has improved, they still lag considerably behind the Ashkenazim. This is reflected in the fact that Ashkenazi Israelis earn 30 percent more on average than Mizrahim.

Despite being in a similar socio-economic boat, it is highly improbable that the Mizrahi and Palestinian citizens of Israel will find common cause – at least not in the forthcoming elections. The bulk of Israel's Sephardim and Mizrahim sit firmly in the anti-Arab, nationalist right. After decades of jettisoning their Arab and Middle Eastern heritage to assimilate into Israel's Ashkenazi-dominated “melting pot”, and expressing bitterness at how their native societies rejected them, few have the appetite to admit that they share much in common with their Palestinian compatriots.

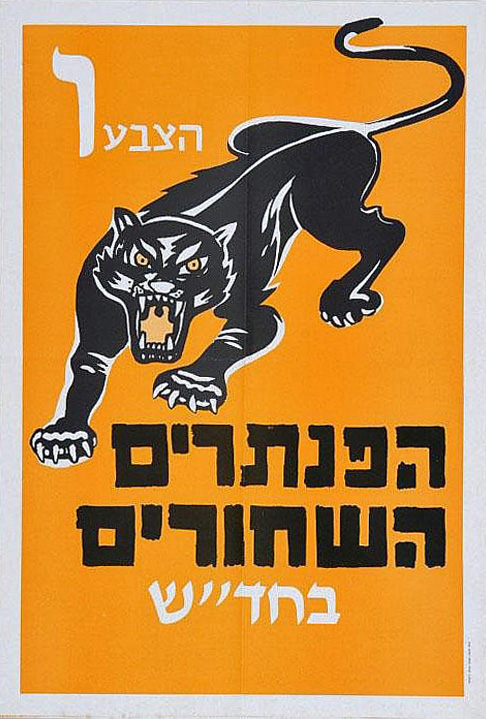

Previous attempts to make this link essentially failed. Take the Israeli Black Panthers, a radical political group that emerged to agitate for Mizrahi rights. Many Panthers believed that the Mizrahi class struggle was intimately connected to that of the Palestinian-Israelis and that social peace in Israel was not possible without peace with the Palestinians. “There will be no equality and no chance for the Mizrahim as long as there's an occupation and a national struggle,” believed former Black Panther Kokhavi Shemeskh. “The national struggle will not be over as long as the Mizrahim are at the bottom of the ladder, and are practically an anti-Arab lever.”

However, this view was not common or popular among the Mizrahim, and the movement faded into obscurity, though it is notable that Mizrahi intellectuals helped pave the way to the peace process.

Were they to set aside their nationalist narratives and embrace their common struggle for socio-economic and cultural equality, the Mizrahim and Palestinian-Israelis could form a formidable voting bloc that would carry significant weight, since together they make up an estimated 60% of Israel's citizenry (about 40 percent Mizrahi and 20 percent Arab).

Beyond their shared socio-economic woes, Mizrahi and Palestinian Israelis have in common that they believe that their history is insufficiently taught in Israeli schools, and that their Middle Eastern culture is still, despite improvements, regarded as inferior. But the younger generation are taking greater pride in their heritage, which could pave the way to joint action to end discrimination against them, dilute the “us” and “them” formula of the conflict, and drive home the realisation that Israel, rather than being a Western “villa in the jungle” of the Middle East, actually possesses a very Middle Eastern socio-cultural complexion.

Moreover, in the bitter identity politics that have resulted from decades of conflict, both the Mizrahim (sometimes referred to as “Arab Jews”) and Palestinians in Israel, contradict the simplistic narrative that Arabs and Jews are completely different animals. In fact, as anyone who has lived in the Holy Land can attest, Israelis and Palestinians share much in common culturally and socially, and the differences within each society are greater than the differences between them.

As I outline in my book, Intimate Enemies, in which I also explore these “conflicting identities, if the civil rights path to liberation is pursued, rather than being stuck in the nationalistic abyss dividing Arabs and Jews, the Mizrahi and Palestinian Israelis may well become the future bridge to peace and justice the two sides desperately need.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is an extended version of an article which first appeared in Haaretz on 3 February 2015.