The real battle against ISIS is political and social

By Khaled Diab

If ISIS is a virus, then fighting it with the antibiotic of ill-conceived deadly force and repression could create ever-more deadly strains.

Monday 9 February 2015

The Abbasid caliphate was the stage for magical tales to fill a thousand and one nights. The Islamic State (ISIL/ISIS) “caliphate” gives us enough horrors to fill a thousand and one frights.

The latest graphic atrocity committed by the Islamist death cult was the apparent burning alive of felled Jordanian fighter pilot Moaz al-Kassasbeh, whose execution reportedly took place in early January.

The brutal murder has triggered horror and condemnation around the world. The news has hit home hard in Jordan, with disbelieving Jordanians stunned by the cruelty of the murder. Spurred on by an angry public mood, Jordan has promised swift retaliation.

“Our punishment and revenge will be as huge as the loss of the Jordanians,” vowed Jordanian armed forces spokesman Mamdouh al-Ameri. And within hours, Jordan began executing jailed ISIS militants, including death row inmate Sajida al-Rishawi.

For his part, Jordan's King Abdullah declared “relentless war” against ISIS. “We are waging this war to protect our faith, our values and human principles,” he said, vowing to “hit them in their own ground”. Towards that end, Jordan claims it has already carried out dozens of airstrikes against ISIS targets

Although the impulse for revenge is overpowering and it may even appear sweet at first sight, it leaves a bitter aftertaste and carries serious consequences.

Fighting fire with fire could very well backfire. Instead of neutralising the threat, the ill-conceived use of force could ignite a wave of violence in Jordan, which is high on ISIS's hit list.

In addition, with the strain caused by 1.3 million Syrian refugees, Jordan is already teetering on the edge of instability. Despite the fact that this latest atrocity is bound to chip away at the limited popular support ISIS enjoyed in Salafist Jordanian circles, all it requires is a small band of dedicated sympathisers to wreak havoc.

If ISIS is a virus, as many contend, then fighting it with the antibiotic of violent repression might well only succeed in creating ever-more deadly strains. In fact, ISIS thrives on brutality. “[ISIS] believes not only in maximum but creative retaliatory and deterrent violence,” Hassan Hassan, a Syrian journalist and analyst who has co-authored an in-depth book about the Islamic State, told me.

One item of required reading among many ISIS militants, Hassan explains, is Idarat Al-tawahush (The Management of Savagery) by Abu Bake Naji which makes the case that “Jihad is not about mercy but about excessive violence, and that the rest of religion is about mercy”.

Where did ISIS pick up such a nihilistic interpretation of Islam? A part of the answer is the cauldron of brutality in which it was conceived. “One cannot understand the violent mindset of ISIS members without recognising that Baathism is one of the ingredients that formed that mindset,” notes Hassan.

This was on full display during the 1982 Hama Massacre ordered by Hafez al-Assad and the past four years of carnage masterminded by his son, Bashar.

In neighbouring Iraq, Saddam Hussein – who bucked no dissent and believed in summary “justice” – used chemical weapons, with US acquiescence, against both Iranians and his own citizens. Add to that the vacuum left by the “shock and awe” of the US invasion which wrought devastation on a scale unseen since the Mongols in the 13th century, and your left with a perfect storm.

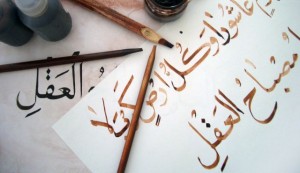

In fact, times of such calamitous ruin are often incubators for virulent extremism. Some eight centuries ago, while the Mongols were laying waste to much of the Middle East, Ibn Taymiyyah formulated a highly influential concept of Salafism and Jihad. These were to have a profound influence on the region, corroding the rationalism and free thought upon which Islamic civilisation's golden age had been built.

What all this highlights is that, though ISIS needs to be fought on the battlefield too, the main battlegrounds are ideological, political, social and economic.

In order to dry up recruits, effective ways need to be devised to show how ISIS's ideology and its self-styled “caliphate” are ahistorical and run contrary to the spirit that once made Islam robust and enlightened.

The socio-economic inequalities, the impunity of elites, their serving of foreign powers more than their own citizenry, and widespread corruption – all major recruiting platforms for radical groups – must be combated decisively.

In addition, it is high time that Arab societies properly defend freedom of belief and thought, in order to inoculate themselves against religious radicalisation by self-appointed defenders of the faith, whether they be individuals, groups or the state.

Those Arab countries which theoretically recognise such freedom need to implement it properly and consistently. Those which do not, such as the Gulf states, must start respecting pluralism and diversity. “So long as [Arab governments] shy away from a clear commitment to freedom of belief, their stance helps to legitimise the actions of groups such as [ISIS],” argues Brian Whitaker, the Guardian's former Middle East editor.

More importantly, the region needs to address its democratic deficit. Despotism from above can and does breed tyranny from below, drawing in the disillusioned and disenchanted.

In short, to prove that violent Islamism is the illusion, we must make freedom, justice, equality and dignity the solution.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is an updated version of an article which first appeared on Al Jazeera on 4 February 2015.