Defeating Hitler’s legacy in Germany

By Khaled Diab

On the 80th anniversary of Hitler's rise to power, Germany provides an inspiring role model for how societies can come to terms with their ugly past.

Thursday 11 April 2013

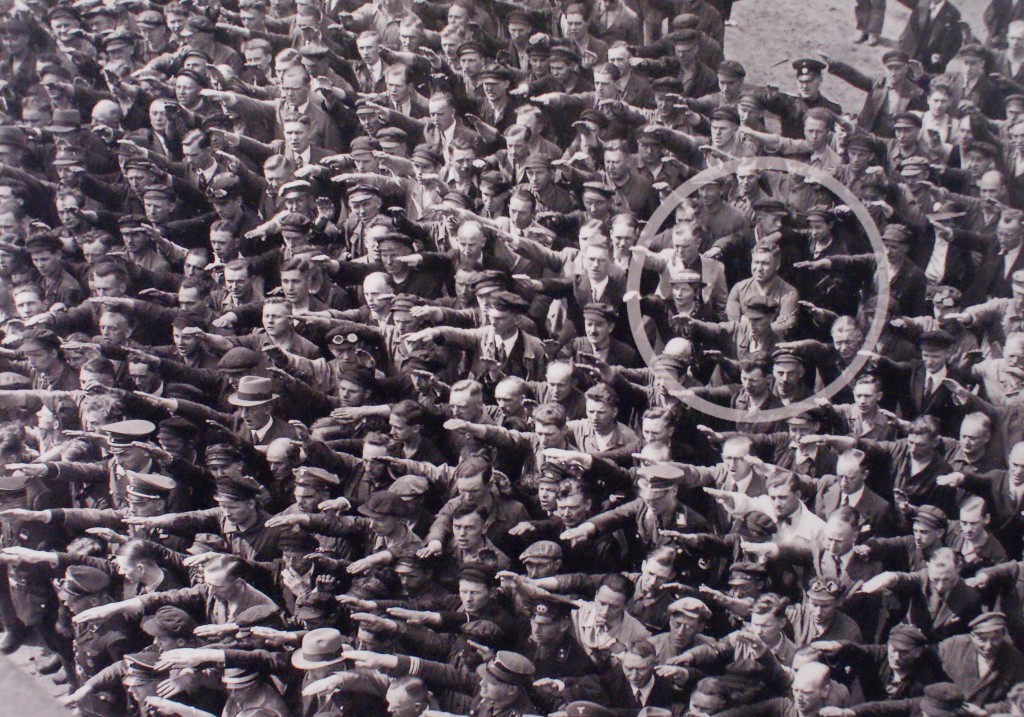

Walking around today's cosmopolitan Berlin, it is hard to believe that it was only 80 years ago this year that Adolf Hitler seized power in Germany. The self-styled “Führer” transformed a volatile yet vibrant democracy into the very definition of a totalitarian dictatorship, paving the way for a war that would claim an estimated 75 million lives, including the systematic murder of 6 million Jews and 5 million people belonging to other stigmatised ethnic groups and minorities.

To mark this important anniversary, the city of Berlin has organised a series of events in 2013 around the theme of “destroyed diversity”. Among the many attractions are open-air exhibitions – sort of pop-up urban memorials – at critical locations around the city which highlight Berlin's diversity during the Weimar Republic in the 1920s and early 1930s, and how this was eventually destroyed by the Nazis.

The portrait exhibitions across Berlin place the wider events of this historical turning point in the human and personal by profiling more than 200 prominent Berliners who both represented the city's immense diversity and subsequently fell victim to Nazi tyranny.

One thing that caught my attention is that though Jews were the Nazi's most hated and persecuted victims, they were not the first. The early purges carried out by Hitler and his cohorts was a kind of political classicide in which opposition politicians, journalists, writers and intellectuals were targeted, particularly communists and leftists.

As a 21st-century observer who knows how this German tragedy ends, one thing that immediately strikes you is how incredibly creative and diverse the Weimar Republic was. Empowered by what some historians regarded as “the most liberal and democratic” constitution of the 20th century, its capital, Berlin, blossomed into a global centre of learning, culture and art.

At its best, Berlin was a free-spirited city where minorities and women flourished in a rare atmosphere of free inquiry, despite the increasingly bloody conflict between the extreme right and left. Had Germany taken a different path, we might today have looked back at the Weimar republic as a “golden age second only to the Italian Renaissance”, the American writer Frederic Grunfeld once claimed.

Although the ugly brand of anti-Semitism which was to become the trademark of the Nazi era was already visible on the political margins – such as in Hitler's very own bestseller Mein Kampf – Jews in Germany were to reach a level of prominence and integration that would be unmatched and unrivalled in the Western world except in the United States in recent decades.

In fact, so deeply woven into the fabric of German life were the Jews that some historians have gone so far as to declare this largely urban population who tended to speak High German, rather than regional dialects, to be the only “true” Germans. “Before Hitler rose to power, other Europeans often feared, admired, envied and ridiculed the Germans; only Jews seemed actually to have loved them,” wrote the late Amos Elon in The Pity of it All: a Portrait of Jews in Germany.

The 160,000 Jews in Weimar Berlin were prominent not just in their traditional domains of finance and business, establishing, for instance, Europe's largest department store KaDeWe, but also in science, including the legendary Albert Einstein who taught at the city's Humboldt University, and philosophy, such as Walter Benjamin.

Jews were also leading lights in Berlin's world-famous culture scene. To name a few, there was the Hungarian-born opera singer Gitta Alpár and Max Reinhardt in theatre. Politics too was increasingly becoming a Jewish theatre, with assimilationist Walter Rathenau becoming the Weimar Republic's foreign minister.

The people named above, like the vast majority of Berlin's Jewish population, were eventually either killed or had to flee Germany for their lives, bringing to a tragic end the Weimar experiment which could have turned out so radically different.

Nazism and World War II left Berlin in ruins and the post-war years saw the city transformed into a Cold War battleground, rather than the interwar intellectual and artistic playground it had once been. The blitzed city was occupied by the four victors of the war: the United States, Britain and France controlled West Berlin, while the Soviet Union occupied East Berlin.

Like Germany itself, Berlin was divided and the most famous section of the Iron Curtain which fell over Europe ran through the city, becoming the stuff of Cold War legend and real-life nightmares.

The Berlin Wall was more than 140km long and separated not only the two halves of the city, but also cut the West Berlin enclave from surrounding East Germany. Physically, the few remaining sections of the barrier still standing and archive images reminded me of another wall which has gone up in the mean time: the one erected by Israel, which is part of the broader physical and mental “Zion Curtain” dividing the Middle East.

Having seen Israel's concrete monstrosity up close, I was surprised by how low the Berlin Wall was in comparison, 3.6m high versus 8m high in parts of the West Bank. But then again the Berlin Wall had deadly features its Israeli counterpart does not possess, such as the infamous Death Strip. That said, the Berlin Wall and the rest of the Iron Curtain running through Germany was constructed on East German territory, while most of the Israeli wall lies on occupied territory.

Both barriers were built, at least partly, for security considerations: East Germany claimed it had built an “anti-fascist protection rampart” to defend its civilians against “fascist elements” while Israel says it is a shield against “terrorism”. In reality, one wall was designed to keep East Germans in, while the other has been built to keep Palestinians out – not to mention to grab more of their land and cement de facto borders.

Both walls have also been the subject of enormous protest internationally, especially by their enemy camps. West Germans came up with the term “Wall of Shame” while Palestinians refer to a “Racial Segregation Wall” or “Apartheid Wall” in English. Graffiti has also served as a powerful tool for expressing opposition to the existence of both barriers. Like in West Berlin, the West Bank side of the Israeli wall has become perhaps the largest protest banner in the world and is covered in street art, including by the world-famous Banksy.

As seems historically inevitable in such situations, at least in retrospect, the Berlin Wall eventually fell. Since that fateful period in 1989, Germany has been reunited and the artificial division of Berlin has come to an end.

With massive investment from the West German government, Berlin has risen from the wastelands of the Cold War to reclaim its place as one of Europe's great metropolises. While the German capital still remains a shadow of its former self, its vibrancy and cultural energy are truly impressive to behold.

But, in my view, the most impressive thing about Berlin, and more broadly Germany, is its ability not only to reinvent itself – losing the war, but in many ways winning the peace – but also its possibly unmatched propensity to come to terms with its ugly past.

In no other capital city I can think of are the crimes of the past so unblinkingly, unflinchingly and honestly on display. In fact, to the outside visitor, Berlin can resemble an open-air museum of historic horror, terror, death and destruction.

A few steps away from Germany's Reichstag building, which houses the German parliament, the Bundestag, is an enormous Holocaust memorial. The haunting, if rather ugly, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe sits on a 4.7-acre site containing hundreds of plain, grey concrete “stelae” of different shapes and sizes.

Berlin is also home to one of the largest Jewish history museums in the world, housed in a unique twisted zigzag of a building. As a sign of just how far Berlin and Germany have come, the city and the country have again become attractive targets for Jewish immigration, with 200,000 mostly Russian Jews, and even quite a few Israelis, doing the once unthinkable and settling there.

Then, there are all the Cold War artefacts and museums, including the archives of the frightening East German secret police, the Stasi. In a similar vein, the Topography of Terror museum provides an honest, gripping and sobering account of the Nazi secret police, the Gestapo, and its paramilitary SS, who once occupied the site.

Of course, even Germany has had its failures, as all the Nazi war criminals who managed to evade justice demonstrate. In addition, some East Berliners, as well as East Germans in general, complain that the baby was thrown out with the bathwater following reunification, and that even the good things from the communist experiment were jettisoned and the entire chapter depicted only as a cause of shame.

Abroad, though the Nazi legacy has turned Germans into the least nationalist of the great western powers and checked the excesses of Germany's jingoistic past, it sometimes also leads to Germany shirking its global responsibilities, such as to speak out and act against the Israeli occupation.

To us in the Middle East, Germany provides a powerful case study in how to lay the past to rest, draw lessons from it and build a prosperous and tolerant future based on cooperation and the exercise of soft power.

—

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is the extended version of an article which first appeared in Haaretz on 7 April 2013.