Behind the ‘Zion Curtain’

By Khaled Diab

Living behind the ‘Zion Curtain' reveals how alike Israelis and Palestinians are and how ordinary people must build common ground on this shared land.

Thursday 19 July 2012

Not so long ago, an Iron Curtain split Europe. Similarly, a sort of “Zion Curtain” still divides the Middle East. But unlike communism and capitalism, Zionism and pan-Arabism are remarkably similar: both have sought to unify and empower diverse cultures who share a common religious heritage, on the one side, and a common language, on the other.

In addition to the physical barriers separating most Israelis and Palestinians from one another and the Holy Land's isolation from the wider region, there are the apparently insurmountable psychological and emotional walls behind which each side takes cover, lest they unwittingly catch a glimpse of the human face peering across that political minefield littered with the explosive remnants of history.

Carrying as little political baggage as possible, I took the rare initiative – for an Egyptian – and stole across this no-man's-land a few years ago in a personal bid to connect with ordinary people and see for myself the reality on the ground. Last year, I returned – this time with my wife and toddler son – to deepen my knowledge and do my little bit for the cause.

Egyptian intellectuals in the past who have preceded me on similar journeys have often faced censure and even ostracism, because their critics confuse dialogue and sympathy with Israelis with normalisation with Israel and approval of its policies towards the Palestinians. Despite the Camp David peace agreement, there is little traffic between Egypt and Israel. However, though I am a rarity in this land, I am by no means the only Egyptian who has made this journey. In addition to diplomats and some Christian pilgrims, a steady trickle of Egyptian pacifists has crossed the border.

Most Israelis are aware of the late president Anwar al-Sadat's historic visit in 1977, but he was not the first Egyptian to cross the border. Some years earlier, when Egypt and Israel were still in a state of war, a young maverick and idealistic PhD student by the name of Sana Hasan threw caution to the wind and crossed the border. During her three-year sojourn, Hasan met just about everyone and did just about everything in her bid to understand her enemy and extend a hand of peace. She even wrote a memorable book about her exploits.

Another notable example is the leftist Ali Salem, the famous satirist and playwright who wrote perhaps the most famous Arabic-language stage comedy of the 20th century. In the more optimistic early 1990s, the portly, larger-than-life Salem mounted his trusted stead – a Soviet-era Niva jeep – and set off on a conspicuous road trip through Israel, which he fashioned into a bestselling book.

Both these brave individuals faced more condemnation than approval for daring to cross enemy lines. Personally, despite some criticism, I have encountered a great deal of positive reactions and encouragement, especially from Palestinians themselves. For their part, many Israelis I encounter are thrilled to connect with a genuine McAhmed Egyptian, and ply me with so many questions that I sometimes feel like I'm the sole representative of an alien race from a faraway planet.

Viewed from the inside, one of the most striking things about this tiny land – whose combined Jewish and Arab population is barely half that of my hometown, Cairo – is its sheer, dizzying diversity, which could be its most powerful asset in the absence of conflict.

Not only do you have two self-identified nations and three main religious groups, you also have enormous ethnic, social and cultural variety within Israeli and Palestinian ranks. Jerusalem is a colourful – and often monochromatic – catwalk of the variously attired faithful, while Tel Aviv and Ramallah are the choice hangouts for the secular.

The downside of this variety is discord. While the outside world is acutely aware of the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians, less noticed are the fault lines within each society, between the religious and the secular, hawks and doves, maximalists and pragmatists, to take just a sample.

Another striking feature is how much Israelis and Palestinians have in common, despite their bitter political differences. For instance, though Israel is variously perceived as an “outpost” of Western civilisation or a Western “implant,” depending on your political convictions, culturally and socially it is also very Middle Eastern, not only because a significant proportion of its population is of Mizrahi Jewish descent, but also because of the direction in which Israeli society has evolved. I am sometimes surprised by how much Arab culture has sunk into the Israeli mainstream, despite the Ashkenazi cultural dominance. In fact, despite Israel's European aspirations, Israel certainly does not feel like part of Europe: it is an odd blend of Middle Eastern colour and tradition, Eastern European austerity and communalism, and, like other parts of the region, sprayed over with a recent layer of superficial American consumerism.

In fact, I would hazard to say that Israelis, Palestinians and the people of the wider Levant resemble each other more than they do the Jewish Diaspora or Arabs from, say, the Gulf. Israelis and Palestinians share a wide range of attitudes to family, education, work, friendship, socialising, driving, and even creaking bureaucracies and rough-round-the-edges finishing. Moreover, even though many Israelis in public are somewhat abrasive and direct, they often have a Middle Eastern attitude to helpfulness and, in private, share regional notions of hospitality, as I have personally experienced.

Moreover, the close proximity in which Israelis and Palestinians live – and the very extensive contact that occurred between the two peoples prior to the current segregation, as recalled oft-nostalgically by older people – has profoundly influenced both sides. In Israel, the Arab influence is clear to see in the culture, music, cuisine and language, while the Israeli influence, as well as the necessities of the conflict, seems to have made Palestinians more individualistic and anti-authoritarian than many of their Arab neighbours.

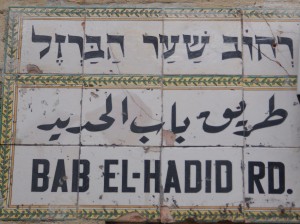

In terms of language, modern Hebrew was profoundly influenced by Arabic, while Palestinian Arabic is increasingly borrowing from Hebrew. Sometimes Palestinians use Hebrew words, yet are convinced they are Arabic, such as “ramzor,” the word for “traffic light.” Moreover, young Palestinian-Israelis speak in a confusing mix of Hebrew and Palestinian Arabic, while older Iraqi Jews liberally inject Baghdadi Arabic into their Hebrew.

When it comes to cuisine, while Israel's acquisition of hummus as its national dish has led to the so-called “Hummus Wars,” Palestinians too have borrowed, albeit to a lesser extent, food from their Jewish neighbours. The prime example is, as I discovered, the surprising popularity of schnitzel among Palestinians.

The decades-old conflict has also profoundly shaped the psyche of both peoples, though it takes a far greater physical and material toll on the Palestinians. Most Palestinians and Israelis alive today were born into conflict, and this has bred a deep level of insecurity, paranoia and despair. This translates not only into positive attitudes towards, for instance, education, solidarity and steadfastness, but also into self-destructive notions that the world is against them, and the conflict is insoluble.

But the conflict is resolvable, not in any dramatic, comprehensive, final manner, but gradually, inch by painful inch, as pragmatism and the need to coexist slowly defeat ideology and intolerance. And the key to that future lies not with the failed leadership on both sides, or the ineffectual international community, but with ordinary people, Israelis and Palestinians willing to work together to transform the land they share into a true common ground.

—

This is the extended version of an article first published in Haaretz on 17 July 2012.

right on Khaled-joon. Keep it up!

do like the ‘zion curtain’ — glad to see your penchant for puns hasn’t wained out there!!

Well, Christian, I’m a leading pun-dit, don’t forget!

Great read, Khaled, thanks.

Khaled Diab’s observations of Israel/Palestine are quite similar to my own, although

naturally he has spent a lot more time with Palestinians than I have.

IMHO reading his observation should be compulsory reading for those who

think they know everything they need to know about the two people living in the 972 International Dilling Code.

Of course Khaled’s actions in living in Jerusalem raise a lot of

question about normalisation etc which I will deal with at a future date

(and ignore now).

A bit of facile, no?

“Zion Curtain” is brilliant.

The great Israeli habit of

combining schnitzel and hummus sums up his point in as far as Ashkenazi

Jews are concerned. What a great read

Great article!