Nothing honourable about honour killings

By Khaled Diab

The taboo surrounding the cruel murder of family members in the name of honour is slowly being broken.

24 June 2009

Though relatively rare, killing a family member in the name of honour should be a cause for shame, not pride, as it reflects a cowardly compliance with inhumane norms.

Killing someone, especially a family member, is something I cannot begin to contemplate. Of course, I realise that it is a sad fact of life that some of the worst physical, sexual and psychological abuses – and even murders – are perpetrated by relatives.

In some ways, it is more horrifying and tragic when abuses are committed not to satisfy some base motives but for the apparently exalted ideal of “honour”. Each year, thousands die around the world – from the Middle East to the Indian subcontinent, and from Latin America to China – in the name of family honour. The victims of these crimes are mostly women.

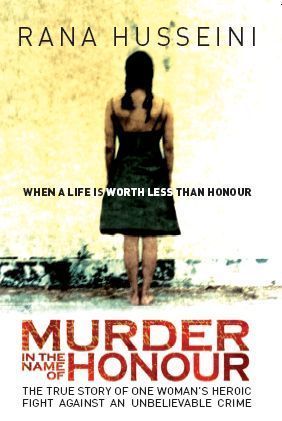

Rana Husseini – a courageous and outspoken Jordanian journalist who has dedicated most of her career to campaigning against this warped cultural practice – will publish a book on the subject at the end of May.

Murder in the Name of Honour (pdf) continues Husseini's groundbreaking efforts to break the silence on this disgraceful crime. The book shines a human light on some of the victims of honour killings, exploring their lives, circumstances and deaths – an epitaph to women whose families and communities would rather forget.

The first case Husseini investigated, back in 1994, was that of Kifaya, a young woman from a very traditional family in a conservative neighbourhood of Amman, who became pregnant after being raped by one of her brothers, Muhammad.

Instead of understanding and sympathy from her family, the poor young woman who had been violated by her own kin was forced to marry a man 34 years her senior to cover up the scandal. When the marriage ended in divorce six months later, the perceived shame led the family to decide that Kifaya had to die, and her other brother, Khalid, was forced to carry out the ugly deed.

Although most honour killings are ordered by men and carried out by men, Kifaya's father, who worked abroad to provide for his family, had no idea of the plot co-hatched by her mother, and the news of her death devastated him. “I would never have allowed anyone to kill my daughter, no matter what,” he confessed to Husseini.

The fact that Kifaya was a victim twice over – once for being blamed for her rape and then being murdered for dishonouring the family – is not unusual in the grizzly annals of this type of crime, where a woman's virginity is worth more than her life. In fact, there are women in the most conservative circles who have paid with their lives for the malicious gossip of others.

Husseini points out that only a small number of men are murdered in the name of honour, despite the fact that they played a major role in the supposed dishonour. Indeed, men – even rapists – do get off lightly in this type of sex-related honour crimes. But her assertion overlooks the fact that there is a whole other world of honour that overwhelmingly claims men as its victims: the vendetta – think Romeo and Juliet or mafia films but in real life.

One place where this dated practice, known locally as ‘el-tar‘, still continues, despite decades of efforts to wipe it out, is Egypt's stronghold of conservatism and tough traditions, al-Said (or Upper Egypt). Highly codified and ritualised, some of these feuds can last for generations, perpetuated by a stubborn belief in “el-tar walla el-aar” (“revenge is better than disgrace”).

It's not just the fact that someone can muster up the ability to murder a loved one that disturbs, it is also the cruel manner and abandon some people bring to the task. One father hired two thugs to rape his daughter for two hours – as punishment for shaming him – before killing her. To my mind, there is no way a father like that can be anything but completely diseased in the head.

The crime can also be cruel on the chosen executioner. Families often choose one of the younger men – often a minor – to carry out the crime because he will probably get off with a lighter sentence, although the powerless youngster is condemned to a lifetime of trauma and often regret. “I know that killing my sister is against Islam and it angered God,” said Sarhan, a young honour-killer Husseini visited in prison. “She was close to me, she was the one who resembled me the most,” he said. “I alone cannot change or fix things in my society. My whole society has to change.”

And change is coming gradually. Thanks to the efforts of Husseini – who has endured slander, unpopularity and even death threats – and other activists and campaigners, the issue has become a very public one in Jordan, and concern about it has grown in other countries, particularly Pakistan.

This breaking of the taboo has incensed many, not because they approve of the crimes but because of the shame and embarrassment it brings upon their societies. At one level, this is understandable: although honour killings are pretty isolated occurrences, many in the outside world have the warped idea that most Arab and Muslim men are bloodthirsty women-bashers. However, sweeping the issue under the carpet is not an option, and it must be dealt with.

Although Jordanian campaigners have so far failed to change the law that enables honour murderers to get off lightly, the struggle is as much about changing cultural perceptions and attitudes as it is about legislation. Public and judicial tolerance of these crimes is wearing thin as the silent majority begin to raise their objections to these barbaric acts. “The protection of every woman's life should be a key issue for the government and community alike,” emphasises Husseini. “Real honour is about tolerance, equality and civil responsibility.”

This column appeared in The Guardian Unlimited's Comment is Free section on 3 May 2009. Read the related discussion.

Very interesting, thanks a lot!

Pingback: Hymen: The Arabs’ Finest Fetish « the long slumber