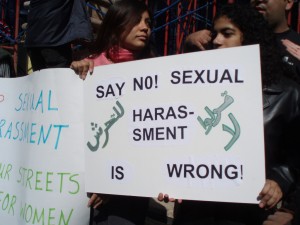

Sexual harassment and toxic masculinity in the medina

In Egypt, sexual harassment is a largely urban phenomenon fuelled by a sense of male powerlessness, insecurity and unrealistic gender ideals.

Wednesday 5 November 2014

In Cairo, the problem of sexual harassment is so widespread that anti-harassment NGOs are now classifying the situation as an out-and-out epidemic. So serious is the issue that in June the Egyptian government stepped in and introduced a law criminalising sexual harassment – a law that to date has only had limited effect. Critics claim the new legislation does little more than treat the symptoms of a social problem – a problem which is unlikely to be solved through condemnation or by criminalisation alone.

“There's an acute need for state intervention that tackles the challenges head on and that addresses the cultural and social dimensions of the issue. If the Egyptian state is serious about combatting harassment, it needs to acknowledge the full scale of the problem. Legislation by itself is not enough,” wrote Yasmin El-Rifae from the organisation Operation Anti-Sexual Harassment on the Middle East Institute portal.

An urban phenomenon

Whereas research has shown that women who are exposed to harassment feel less secure about walking about on their own and, to some extent actually choose to avoid public spaces, there have been few studies into the factors that motivate men to harass women.

“We know very little about the perpetrators. After all, no-one is going to put his hand up and admit that he's done such things, let alone tell us why he did it,” explains Marwa Shalaby, a the director of the Women and Human Rights in the Middle East programme at Rice University's Baker Institute for Public Policy.

She adds that when it comes to determining why men commit acts of harassment neither age nor religion nor profession seem to be factors. However, evidence does show that harassment is more prevalent in the towns and cites than in rural areas.

But just what is it that drives men to accost and harass women? One person who has been trying to find an answer to this question is Shereen El Feki, who researched and wrote the book Sex and the Citadel – a factual novel about sex in the Arab world today.

An expression of impotence

When the so-called Arab Spring reached Egypt at the beginning of 2011, the fact that women and men could stand side by side demonstrating for the same rights was one thing that was highlighted as exceptional. During the protests, many women became the victims of violent assaults. However, during the first days of the uprising, Egypt witnessed a rare and unique coming together of the women and men who jointly took over Tahrir Square. Together, they were fighting for the same thing. In her book, El Feki argues that this sense of struggling for something meant that the men taking part in the protests felt less need to elevate themselves above the women. On the basis of her own experiences, she writes: “These events have clearly shown that when men have a sense of motivation and purpose they change the way they behave towards women.”

Shereen El Feki's argument is backed up by Samira Aghacy, equality researcher at the Lebanese American University in Beirut. One of her areas of study has been masculinity, and she argues that the patriarchical social order prevalent in many places across the region also serves to oppress men – and this oppression is then reflected in the men's behaviour towards women.

“Many men feel impotent, marginalised and incapable of doing something positive or contributing to the reconstruction of their country or the way it's being run. It leaves them feeling very frustrated, and they often take their frustrations out on women,” explains Aghacy.

Patriarchy, performance and power

One of Samira Aghacy's major studies in this area examined how Arabic literature has been portraying men since 1967. Here, she points out, it is clear that masculinity and manliness are associated with having power. Yet only a few Arab men have actually held power over the past decades, so men have also been victims of the patriarchical society. Men are oppressed in a similar way to women, but they have a different conflict because they have been brought up to be in control. They feel castrated and inadequate because they are unable to perform in the way they feel men are expected to perform.

“It all comes down to the way that we're brought up. That's the way power relations play out across large parts of the region. Men are brought up to hold the power, so if they don't have any power, don't earn enough, and don't feel that they have anything to say, then they have to demonstrate power in another way,” explains Aghacy.

In other words, there is incongruence between what is expected of men and what men actually can live up to. According to Egyptian journalist and blogger Khaled Diab, the problem of sexual harassment is also linked to the polarisation that has been taking place in many Arab societies over the past years – particularly in Egypt.

“The Egyptian revolution has meant that the underlying polarisation between progressives and conservatives has transformed from cold war to active conflict. On top of this, huge differences in income, wealth and education have also played a role,” Diab observes. “When anger and resentment begin to flourish within a society, it's often the most vulnerable who end up paying the highest price –whether they be women, children or minorities.”

Torn between tradition and modernity

When a woman student at Cairo University's Faculty of Law was sexually harassed by a group of men in March, the university's rector suggested afterwards that it was her own fault because she was dressed in such ‘unusual' clothing: tight jeans and a pink hooded top. Khaled Diab reacted by posting a photo on Twitter taken around the 1950s or 1960s at Cairo's Al-Azhar University. In the picture, a group of young women who are not wearing headscarves are being taught by an Islamic scholar. “Women used to study at Al-Azhar without covering their heads, and now Cairo University is blaming this woman's clothing for her attack,” wrote Diab on Twitter.

“Since the end of the 1970s, conservative forces have been steadily gaining ground. But over the past year, women and progressive men have begun refusing to be intimidated, and they've become more self-aware and more radical. This has provoked a violent backlash from alarmed and displeased elements within the conservative camp,” explains Diab.

“Right now, Egypt finds itself in a state of limbo, torn between tradition and modernity. This means that women have lost the protection of their bodies that a patriarchical honour system affords, but they have yet to win the protection that modern equality offers,” he adds.

For Mette Toft Nielsen, MA in culture, communication and globalisation, the reason men act the way that they do is the million-dollar question. In connection with a research project for Aalborg University, Denmark, she is currently spending two years living in Cairo studying the conditions of women in Egypt. As part of her studies, she has also been looking into the issue of sexual harassment.

“I've come to the conclusion that providing a clear answer as to what caused sexual harassment it's simply too ambitious. There are thousands of hypotheses and assumptions out there, but most of them are just too difficult to prove or disprove,” she explains.

Conservative gender roles

According to Mette Toft Nielsen, sexual harassment should not be seen as an expression of how men regard women. “It's interesting because that's how we typically look at it – that the way men regard women is grotesque. That men are misogynistic pigs and women have a real tough time of things. But I personally don't believe that that's actually what's going on,” she explains.

She continues that while it is clearly women who suffer most from male dominance, the responsibility for changing things does not necessarily lie with men alone. According to Nielsen, men's attitudes towards women stem from the fact that the men are products of a culture that is governed by very strong gender-role expectations. There are traditions and expectations – and the women are also complicit in upholding these.

“In the West, we often have a subject/object approach to things: the subject – the person who acts and takes action – is the man; the object – the person who is affected by the action and who is seen – is the woman. In this way of thinking, the man can also be seen as the one who can change the situation he finds himself in. And this is something I disagree with strongly. I believe that there are a lot of men out there who really do want to change these things,” notes Nielsen.

One widely touted explanation for sexual harassment is that the heckling and accosting are a result of the men's sexual frustrations from living in a culture where sex is only permitted within marriage, and is therefore something many young people cannot indulge in. But Mette Toft Nielsen does not buy this theory.

“Fist of all, many of the men in Cairo who sexually harass women certainly don't lack sexual experience. Secondly, I'm not at all convinced that sexual harassment has anything to do with sex in the first place,” she asserts.

“I see this harassment first and foremost as an issue of power. Not power as in control – but power as in preserving something that there once was,” she explains, and points out that this is purely based on her own experience and observations and not something based on scientifically proven facts.

“Perhaps this explains why sexual harassment is much more prevalent in the towns and cities than in rural areas. In urban areas, people are witnessing change – particularly economic change. Men are witnessing many women entering the labour market, taking on well-paid jobs and being professionally accomplished,” Nielsen describes. “Many students at the universities are women, and from a career perspective they pose a real threat to the men. So I could imagine that it's a question of changing positions and changing power relations. After all, if the man loses his role of looking after the woman what is there left for him to do?”

____

This article first appeared in WomenDialogue on 21 October 2014. Republished here with the author and publisher's consent.

Pingback: MEDIA ROUND-UP ON THE CITY - NOVEMBER 2014 | Égypte en Révolution(s)

Apparently, it’s an issue that’s making a comeback:

http://www.radio1.be/haut…/seksisme-meer-aanwezig-dan-ooit