Egypt’s pharaoh illusion

By Khaled Diab

The idea that Egyptians are docile sheeple who need a pharaoh to shepherd them is a myth that dates back to the not-so-ancient times of the Nasser era.

Tuesday 7 June 2016

“I am not pharaoh… After two revolutions, nobody who occupies this chair can become a pharaoh,” Egypt's president Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi reportedly told a select group of intellectuals and thinkers a few weeks ago, insisting that he accepted and respected criticism.

Despite the president's repeated assurances, Egypt has been in the throes of an intensifying crackdown since the weeks leading up to the fifth anniversary of the 25 January 2011 revolution.

This has had the counter-effect of galvanising a rising tide of dissent, as epitomised by the remarkable media and protest campaign spearheaded by the Journalists Syndicate to defend press freedom, call for the resignation of the interior minister and demand an end to repression.

The latest high-profile victims of the state's clampdown is ‘Street Children', a group of young satirists whose impromptu songs mocking Sisi and his regime, performed on street corners, have become an online sensation, attracting hundreds of thousands of views each.

After the initial arrest of one of their singers, known as Ezz, for allegedly “insulting” state institutions, the remaining members of the band were arrested soon after. The group seems to have upped the ante in their latest videos in which they ridicule “Sisi, my president”, the army and the security services – criticising the devaluation of the pound, the Suez Canal expansion and the transfer of two Red Sea islands to Saudi Arabia – and call on Sisi to “have some shame” and step down.

That a band of six young men armed with little more than their vocal cords should provoke such an autocratic reaction is bound to cement, rather than disprove, Sisi's reputation as Egypt's latest “pharaoh”.

Some see that as no bad thing. In America and Europe, many commentators are convinced that Egypt can only be ruled by a strong man and so crowning a new “pharaoh” was the only way to save Egypt.

This attitude has its native advocates too, not only among the political old guard but also among those who saw Egypt hanging over a precipice and concluded that the only way to stop it from falling into the abyss was to choose the pharaoh-president over people power.

One-upping other despot worshippers, former antiquities chief Zahi Hawass likened Sisi to a specific pharaoh, Mentuhotep II, who reunited Egypt after it split into two rival kingdoms.

This pharaoh-isation of Egypt's leaders suggests that there is some kind of continuous, almost dynastic, line which stretches back to the dawn of history, leaving the impression that this is some kind of innate national trait.

There are those who subscribe to the pharaoh theory of Egyptian history in an ill-informed attempt to explain away modern autocracy. Some outsiders are driven by an orientalist conviction that Egyptians do not desire nor understand democracy, while those who prop up Egypt's dictators can sleep easy in the knowledge that this is ultimately what Egyptians want.

Proponents of the theory at home use it to dissuade Egyptians from rising above their station and to demonstrate the apparent futility of seeking to change what has always been so.

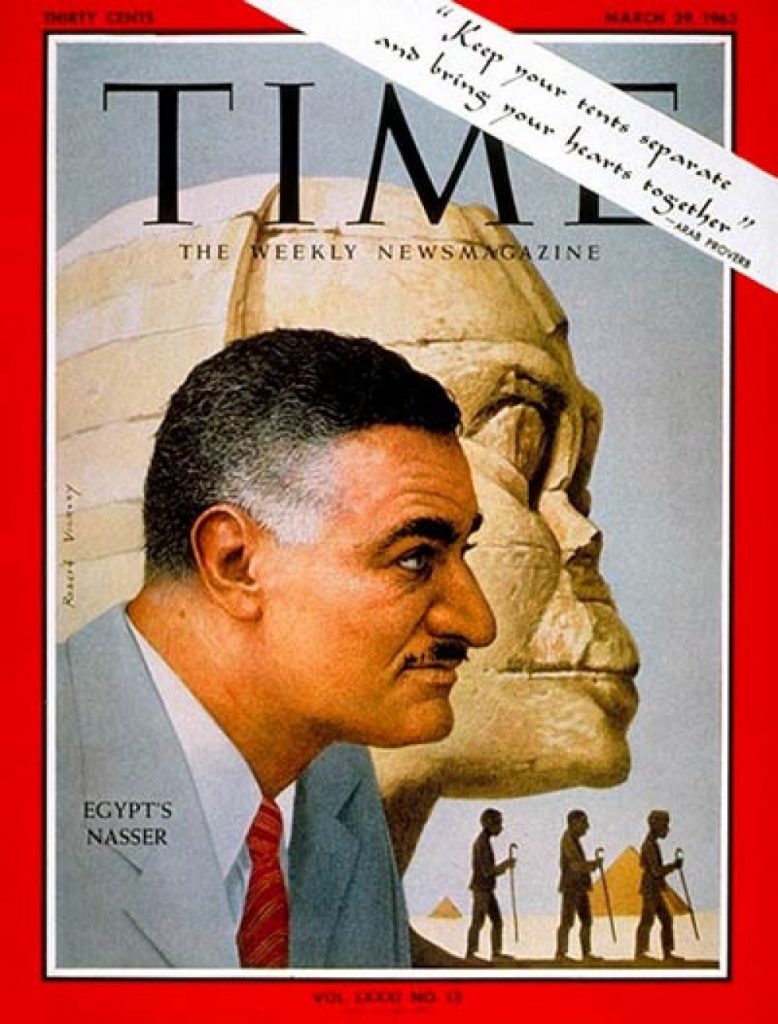

The trouble is this is largely a myth – inspired more by Abrahamic scripture than actual history – that started some six decades ago, namely with Gamal Abdel-Nasser, the leader of the 1952 revolutionary coup and the Egyptian republic's second president.

But even this wasn't inevitable. The Free Officers which Nasser led were initially committed to civilian rule and strengthening Egypt's parliamentary democracy. And given the more than a century of struggle to build a modern, egalitarian and fair state which generations of reformers had been waging, this early commitment to democracy was unsurprising.

However, Nasser reneged on the Free Officers' promise to transition back to elected civilian rule. In this, Nasser was driven by a fervent desire for his revolution to succeed and the plain old-fashioned hypnotising lure of power. “If I held elections today, [Mustafa] al-Nahas would win, not us. Then our achievement would be nothing,” he said in a meeting shortly after the coup.

In this endeavour, he faced stiff opposition, namely from what he had assumed was his figure-head president, Muhammad Naguib, who wanted the army to return to its barracks after having accomplished their mission of unseating an unjust, British-backed regime.

Instead, Nasser placed Naguib under house arrest, abolished all political parties and started a brutal crackdown on secular and religious dissent, imprisoning liberals, communists and Muslim Brothers. “[Nasser] recognised that democracy was the clear enemy of the cult of character he was trying to establish,” posits journalist and revolutionary Wael Eskandar.

Nasser's popularity on the Arab street, coupled with shrewd propaganda, enabled him to turn the newly established republic into his personal fiefdom rather than a state of institutions and checks and balances.

In this project, Nasser was inspired not by his ancient pharaonic ancestors nor facilitated by some native Egyptian subservience to the “pharaoh”. It was part of a 20th century trend of the larger-than-life dictator empowered by the advent of mass media. Compared with Stalin and Mao, Nasser was, nevertheless, a gentle pussycat.

Even during Nasser's tenure, which combined popularity with brutality, many Egyptians refused to believe the lie that they were docile sheeple who needed a father figure – or in the case of Nasser, an amiable brother, cousin or charming boy next door – to shepherd them. In actuality, opposition was often brave and determined.

In a pattern that would repeat itself continuously over the decades, this forced the regime to find other channels to accommodate Egypt's diverse and dynamic political currents, giving Egypt, even at its worse, more representative governance than most other Arab states.

Moreover, co-option was often, and remains, a more effective tool than coercion, leading many to hitch their cart to the wagon train. “There were many who embraced [Nasser's] leadership as an active, not passive, choice because, rightly or wrongly, they envisaged themselves as making gains out of it,” points out Jack Shenker, the author of a major new book on the Egyptian revolution.

Today, the regime is also employing a blend of coercion and co-option to protect the state that Nasser built, and Sadat and Mubarak renovated. But without Nasser's skill, charisma and monopoly of the media, and with a restive population that is no longer willing to buy yesteryear's mythology, this enterprise seems doomed.

Sisi is right, no Egyptian president can become a “pharaoh” anymore.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is the updated version of an article which first appeared on Al Jazeera on May 2016.