Podcast: Egypt’s cartoon villains and heroes

By Khaled Diab

The battle between Egyptian revolutionary and counterrevolutionary forces is being played out in caricature.

Thursday 18 February 2016

It's an arresting image – both figuratively and literally. A caricature of Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi has the Egyptian president's hands pressed over his tightly shut eyes. An anxious frown is knitted deep into the dictator's brow and his mouth is downturned as if the weight of the country hangs off it.

Entitled ‘Shy president', the caption reads: “I don't like being drawn.”

The cartoon was the brainchild of the outspoken pro-revolutionary cartoonist Mohamed Qindeel, who goes by the nom de plume Andeel.

Andeel's caricature was a graphical protest at the arrest of fellow cartoonist Islam Gawish. “When I read the news about Islam I started drawing Sisi's face before I even knew what I'd have him say,” Andeel says. “The fact that they wanted people to think they are not allowed to draw Sisi was enough to make me sure that I have to draw him.”

Gawish's cartoons, which tend to be simple, child-like ink drawings, have become a runaway success with Egypt's young. One memorable Gawish cartoon mocks the duplicity of the regime's rhetoric compared with its reality. It features a balding stickman who represents Sisi or his regime.

“You need someone who will embrace you. Come here,” the authority figure urges a group of long-faced youth. The punchline arrives in the final panel in which the youngsters are still in Sisi's embrace but are now standing inside a cage, with him on the outside.

Many, including Andeel, are convinced that cartoons like this were the reason behind Gawish's temporary detention, as Egypt slowly reverts to the bad old days when mocking the president was a red line.

Following massive uproar, Gawish was released. However, his short-lived detention may have already served its intended purpose. “[Gawish] is young and mostly active on the internet. He doesn't belong to the old-school intellectuals,” explains Andeel. “So making people believe he is targeted is supposed to make people realize that the authorities are as present online… as they are in the physical world.”

And with over 1.7 million followers on his Facebook page alone, Gawish is a big fish to net.

Egypt is in the grips of a major crackdown on dissent, with thousands of activists, artists and journalists languishing behind bars or fleeing into self-imposed exile. One prominent example of this is Ramy Essam, whose daring, mischievous lyrics transformed him into the unofficial “singer of the revolution”. He is now living in relative obscurity in Sweden.

Those left behind live in constant anxiety or fear that the arbitrary net of Egypt's resurgent autocracy could nab them next. “I'm thinking about the possibility of going to jail for the first time in my life,” admits Andeel.

But arrest and intimidation aren't the only weapons in the regime's arsenal. There is also the subtle and not-so-subtle art of counterrevolution.

There has been a concerted campaign to erase the revolution's artistic legacy, including the literal whitewashing of Egypt's flourishing revolutionary street art.

There has also been a clear, if piecemeal, effort to co-opt artists, including actors, singers and writers. Many of them have quite literally been singing his praises, in a revival of low-quality, cloying patriotic odes to the president and to Egypt which I and many others had hoped the revolution had relegated to the dustbin of history.

Cartoonists, too, in the state-owned media and some pro-regime outlets have played their part in this effort. “These cartoons tend to mirror official policies, whether that be the president's speeches, government slogans, or campaigns,” observes Jonathan Guyer of the Institute of Current World Affairs who specialises in Egyptian political cartoons.

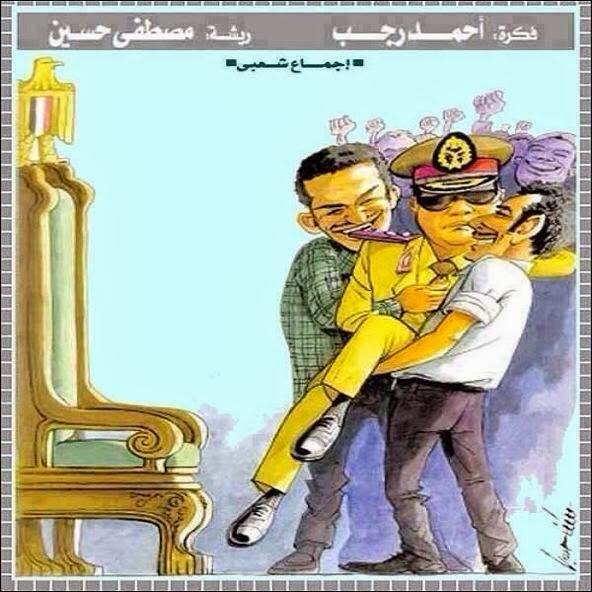

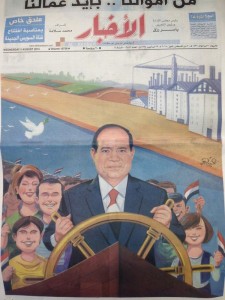

Sisi's official anointment as president and the inauguration of the much-hyped extension of the Suez Canal were particularly active periods for counterrevolutionary artists.

In contrast to the unflattering portraits of Sisi by Andeel or by the renowned graffiti artist Ganzeer – who depicted the president with a television head on which was the face of a cartoon bunny, the portrayals of many pro-regime artists couldn't be more ingratiating – the portrayals of many pro-regime artists couldn't be more ingratiating.

There is Sisi the conscientious, earnest labourer straining under the burden of carrying the country on his shoulders. There is also Sisi the skipper of the good ship Egypt, navigating it through narrow, perhaps even dire, straits, while trusting, smiling, stupefyingly grateful, flag-waving Egyptians stand behind him.

One common motif is to depict Egypt as a woman, “Um el-Dunya” (Mother of the World), with Sisi as her son, guide and defender – an image, Andeel believes, is “psychologically reflective of tyranny”.

These staid, formulaic cartoons lack, in the words of Guyer, “the artistic nuance or linguistic wordplays of some of the more rabble-rousing and creative illustrators for independent media outlets”. Andeel maintains that the desire for freedom means that rebel art “will revolve around fresh ideas” and be free of monotony and repetition.

That's not to say that pro-regime art always lakes creativity or artistic merit. The propaganda songs of the Nasser years are still popular today. But that was a time in which artists seemed, despite their misgivings, to believe in the national project. They wanted optimistically to help construct a nation, not keep one from imploding.

Those supporting and praising Sisi aren't all hired pens, some genuinely believe his rhetoric and project, while others fear the alternatives to his rule.

This public sentiment could be gleaned in the “Sisi-mania” which gripped Egypt in 2013 and 2014. Citizens spontaneously produced and consumed Sisi paraphernalia, from chocolates to perfume, in a surreal show of leader love, even lust, in the form of Sisi lingerie.

With such a public mood and mainstream media hysteria, some fear that the window for subversive caricature and radical art in Egypt has shut. But Sisi's heavy-handed repression and failure to turn Egypt around has replaced the mania with apathy in somen and bubbling restiveness in others.

Many who had offered their conditional love are withdrawing it. An example of this Guyer points to is Amro Selim, who was one of the first cartoonists to lampoon Hosni Mubarak in caricature, in the former dictator's final years. Angered and fearful of Mohamed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, Selim was a supporter of Sisi's violent power grab.

But Selim has gradually grown more critical. In one scathing cartoon, he has Sisi sitting on the head of a troubled journalist, like some sort of fat genie, watching carefully what the embattled hack is writing.

Moreover, biting satire has been an Egyptian staple for decades, if not centuries, even if its mainstream form was forced to focus on social issues during oppressive periods.

When Egyptian rulers oppress, the satirical press doesn't go away it just goes underground. This is reflected in Egypt's first satirical magazine, Travels of the Man in the Blue Glasses, which was first published in 1877.

After it was banned in Egypt, its founder, Yaqub Sanu, began to publish it in Paris and thousands of smuggled copies continued to enjoy a massive underground following back home.

With social media and the internet's intrinsic subversiveness and the endless possibilities they opens up for artists, the underground scene has grown exponentially since the days of Sanu.

And what sizzles and simmers underground is bound to, when the moment is right, bubble up to the surface again, turning counterrevolution back into revolution.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This report was first broadcast on the BBC World Service's The Cultural Frontline on 13 February 2016.