Automation: On the high-tech path to destruction

By Khaled Diab

Rather than humans becoming enslaved by robots, machines have become the new slave or serf class, with devastating consequences for society and the environment. We desperately need a more humane and sustainable approach to automation.

Monday 23 November 2020

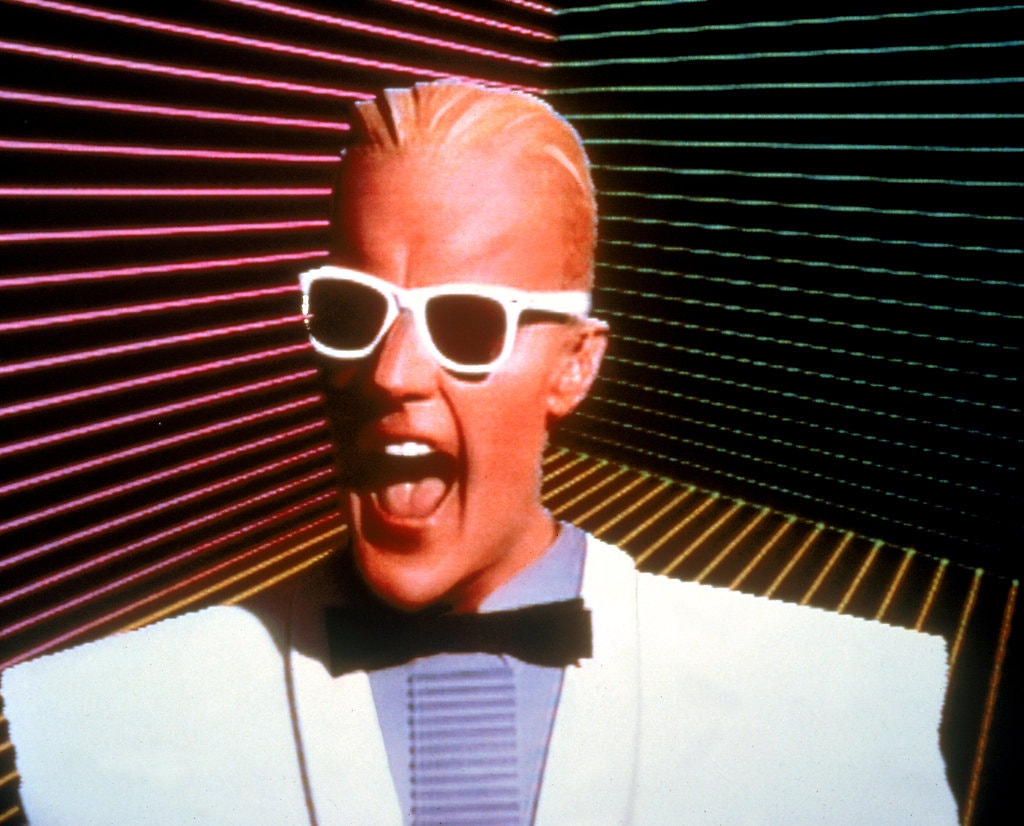

In the mid-1980s, Max Headroom, a TV personality with a zany sense of stuttering satire, was possibly the world's first Artificial Intelligence (AI) superstar. Back then, of course, computer technology was not yet up to this mammoth task and the intelligence behind this hilarious parody was very much human, as was the actor, Matt Frewer.

In a way, we have not only reached but exceeded the dystopian-utopian future foreshadowed by Max Headroom. However, instead of our lives being dominated by advertising-mad TV corporations, they are being overwhelmed by advertising-mad social media corporations that monitor and record the minutiae of our behaviour.

Moreover, technology has advanced so much over the past 35 years that instead of a human convincingly playing a machine, we now have machines convincingly acting like humans – so much so that we can create entire computer-generated worlds and characters.

The once unthinkable advances in computing power, robotics and AI have enormous implications for society, not just in the future but in the present. Although we are still some way off from humans becoming obsolete, much of human labour has already become surplus to requirements.

A visible example of this is the (almost) workerless factory (known as ‘lights-out manufacturing). Whereas a couple of generations ago, a typical factory would employ hundreds if not thousands of workers, today, many manufacturing facilities are more or less completely automated.

One futuristic factory in Japan behaves like some form of robotic womb, using robots to build robots without the need for human intervention. Bur rather than being located in the distant science fiction future, this facility exists in the science fact present and recent past.

While full automation is relatively rare, partial automation is everywhere. And this is not just the case for agriculture and manufacturing. The service sector, which has long been viewed as the place where new jobs would be created, is also falling prey to automation.

This is reflected in the diminishing number of service sector workers required to generate wealth. In the 1960s, telecoms giant AT&T was worth $267 billion in today's money and employed three quarters of a million people. Google, in contrast, is worth considerably more ($370 billion) but employs far fewer humans, only about 55,000.

These innovations have brought some undoubted benefits. This is reflected, for example, in how, during the coronavirus lockdowns, millions were able to switch to working from home and people with broadband access were still able to connect socially while distancing physically. But these are the fortunate ones.

At their best, new technologies work in synergy with humans, freeing us from drudgery and bolstering our mental capabilities. At their worst, they force us to behave more like machines in order to compete with them and keep our jobs.

However, with the way our economies are currently structured, the fruits of automated labour have largely gone to multinational corporations, their shareholders and top executives – the feudal class of the information age.

Unlike in a dystopian science fiction novel or movie, humans have not become enslaved by robot masters. Rather, high-tech machines are the new slave or serf class. Moreover, they work relentlessly, accurately and obediently without needing sleep, paid holidays, health insurance or organised unions. No wonder they are so loved by their masters.

And the day is possibly not far off when describing machines as “slaves” or “serfs” will no longer be hyperbole, as artificial intelligence morphs and evolves into artificial consciousness, which would have far-reaching ethical implications.

The working classes (i.e. people who rely on their labour), from factory workers to middle-class professionals, have seen their status corroded, with a growing number unable to find work or forced to labour under deteriorating conditions.

This process has been a long time coming and warnings about how the “cybernation” of our economies would create “a permanent impoverished and jobless class” date back to at least the 1960s.

It is a testament to the genius of new technologies and their proponents that the worsening economic situation and prospects of ordinary people have triggered far more xenophobia than technophobia, with people blaming migrants and foreign workers for stealing their jobs, welfare and status.

Socially, the destructive dimension of automation has reached a point where it often seems to outweigh the constructive potential. The widening gap between the productivity of capital and labour, along with deregulation and tax avoidance by the super-rich, have led to a devastating chasm between the haves and have-nots, fomenting popular unrest and social conflict.

Thanks to unprecedented technological progress, income and wealth inequalities today appear to be higher than they have been at any time in human history, even if the material wealth of the poor has risen.

With us primed to see the green potential of new technologies, one underappreciated and overlooked aspect of high-paced automation is its devastating environmental impact, which looks likely to multiply in the future.

Today's economy produces massively more per unit of human labour than ever before, which leads to enormous levels of overproduction, even if each individual item is produced more efficiently.

Keeping people in work or creating new jobs means that this overproduction needs to be matched by an equivalent level of overconsumption. This overcapacity is a major factor behind our shift to the contemporary throwaway, disposable culture.

Moreover, new technological tools and automation have become such an integral part of modern labour that the ecological footprint of work has skyrocketed. This is also visible, paradoxically, in the most ancient of jobs, farming. For example, although agriculture only employs about 4% of the European labour force, it accounts for about a tenth of Europe's greenhouse gas emissions.

Little wonder, then, that a growing body of research indicates that shortening the working week would be good not only for workers' health and wellbeing but also that of the environment. Shaving a day off our working week would reduce our carbon footprint by as much as 30%, according to one study that is almost a decade old.

The above is not an argument for technophobia, but a plea for techno-realism. To gain the maximum benefit for humanity from technological progress, we must move beyond the narrow focus on economics and profit maximisation and look at the wider social and environmental picture.

No major new technology should be rolled out before a thorough social, environmental and ethical assessment has found that its potential benefits will outweigh its costs. Some sectors, especially areas where human contact brings with it intangible social and emotional benefits, could be partially de-automated to preserve and create jobs and reduce alienation.

More fundamentally, the fruits of automation urgently need to be better and more evenly distributed. This can be accomplished through truly progressive taxation, taxing capital at a higher rate than labour and introducing such schemes as a universal basic income for everyone.

In the throes of the Great Depression, the legendary economist John Maynard Keynes, in an essay titled ‘Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren', cast aside the economic pessimism of the time and predicted that within a century we had the potential to inverse our working life, with two days of work and a five-day weekend, or three-hour daily shifts of work.

The fact that this reality has not yet come to bear, nearly 90 years after Keynes predicted it, is not due to a failure in his foresight but to our collective failure of imagination and our failure to exploit our economic bounty for the good of all.

“There is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy,” Keynes presciently foretold.

It is high time that our societies overcame this dread and that we collectively strive to enjoy our unprecedented material abundance through the pursuit of happiness for the many rather than the pursuit of unfathomable wealth for the few.

_________

This article was first published by Al Jazeera on 16 November 2020.