Unsung death on the Nile – Part II

By Khaled Diab

Arriving in Thatcherite Britain was a shock to mother's leftist, post-colonial worldview, but she adjusted, managed to admire her new home and made friends from all walks of life.

Thursday 17 August 2017

After a month or so of kicking our heels in Tripoli, something gave at the Home Office in London, and we finally found ourselves on a flight bound for England. For the first weeks and months, culture shock and adjustment were the order of the day. In addition to English, which my mother never fully mastered, though she became proficient, there was also the exotic and oft-inexplicable ways of the English. This included how sacred privacy was and how distrusting of strangers around their children many English people were. I recall my mum being chided for adjusting a sleeping child in a pushchair or giving a perfect stranger a parenting tip.

Although I was very young, I still recall mum's dismay and bewilderment just walking down the street, such as when she came across a young couple snogging in public. One phenomenon which seems to have caused her cultural and anthropological compass the most confusion was punk culture. She just couldn't get why anyone would purposely pierce themselves full of pins, rip their new clothes, dye their hair unnatural colours and listen to the loud “banging of pots and pans,” as she called it.

Arriving in Thatcherite Britain must have been a shock to mother's leftist system, and the idea of living in Egypt's former colonial master was tough on both my parents' pan-Arab sensibilities. However, mum was more honest and pragmatic. In fact, she often criticised my father for having little good to say about his adopted home and his failure to make English friends, preferring to hang out with secular, leftist Arab intellectuals instead, who were in great abundance in London if you knew how to find them. Mum, in contrast, gave credit where credit was due. She was pleased to be living in such a relatively free and open society, she oozed praise for Britain's education system and work ethic, and even admired Margaret Thatcher's strength and charisma, though she could never abide her politics, and was distressed by Maggie's brutal handling of the miners' strike.

A tree-lined street in southwest London is where we spent the bulk of our years in England. I have mostly fond memories of our time there, particularly the long, play-filled holidays, with their endless summer days.

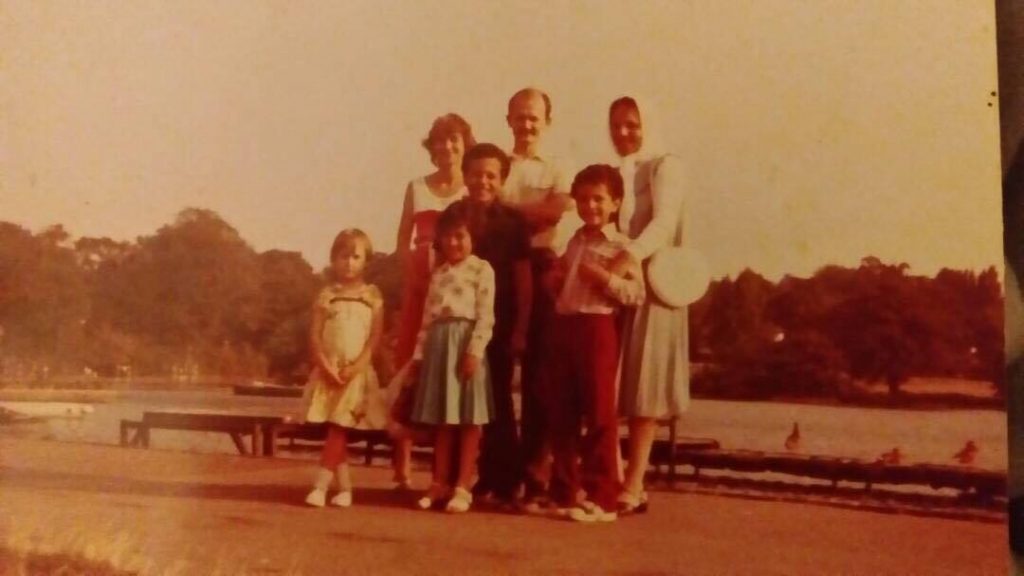

Growing up in London, I recall how mum's eclectic circle of friends included and embraced everyone, from fellow Arabs and Muslims, to Indians, who introduced us to long Bollywood epics, Afro-Carribeans and native Brits. My mother is the only person I knew who not only invited Jehovah's Witnesses into her home, offering them tea and biscuits and a non-judgmental ear, but built up an enduring friendship with one, a fellow immigrant, a French woman married to a Brit who was a mother of seven. But I imagine she would have made an exception for the likes of Donald Trump, as she never tolerated fools, especially not dangerous ones.

My mother left such an impression on some of her old friend, that they tried to track her down many years later. A few years ago, the younger son of one of mum's Pakistani friend saw my byline and contacted me to see if I was the son of Iman Diab (my mum had morphed into another woman in the UK because officialdom couldn't yet grasp that a married woman could have her own name, Iman Khattab). He told me that his mum was desperate to get in touch with mine – and they did. Mum even set us up with a kind of surrogate grandmother, and perhaps a substitute mother figure for herself. Nancy, a reserved but extremely affectionate English pensioner, would visit us regularly and we would visit her, or go to the park together. She also was a sympathetic ear to my mum's trials and tribulations.

Although many aspects of her life in London made her happy, especially how her kids seemed to be thriving there, there were many dark clouds. One was her chronic homesickness, which she had learned to live with or to conceal better as the years passed. She was so nostalgic for Egypt that she accidentally painted us an almost fantastical portrait of our homeland. And I didn't yet know better or different. For me, Egypt had gone from being a solid, real homestead to become a strange and exotic distant land to which I somehow belonged but which was becoming more and more foreign the older I got.

In all the years we lived in Britain, we never once returned to Egypt. My father was still a wanted man, for thought crimes he did commit. And my mother was concerned that if we went for a visit without him, we ran the risk of being effectively held hostage again by the regime. Melancholy became grief when mum lost both her mother and one of her sisters while we were in England, unable to return, even without my father, on family visits, for weddings, engagements, illnesses or funerals, in case the authorities detained us again.

When her sister, Huda, who was also living abroad, died in a car accident, the news hit mum as if she herself had been in a serious traffic collision (she even later named her small business in her late sister's honour). When her mother, my long sick but tough-as-nails Setoo, passed away, it was like the foundation upon which mum's life was built had caved in. I don't believe I have seen her cry as much as in those weeks following my grandmother's death – the distance and the fact that she hadn't seen her mother in a few years must have added to the grief. But today I understand the mother-sized hole left inside you when a death like this occurs.

My mother's only connection to home, in those pre-social media days, was expensive international calls. As my grandfather didn't own a phone, which was difficult and expensive to acquire in Egypt at the time, he, my grandmother and mum's unmarried siblings would have to pile into their neighbour's apartment to chat with us, each snatching the receiver and a few precious words with their faraway relatives. It made mum melancholic to think that circumstances had forced her to leave her boisterous family, with whom she had grown up in cramped quarters, yet again. Though mum travelled a far bit during her life, she was not a voluntary or intrepid globetrotter. Despite her curiosity towards other cultures, this interest was mostly intellectual and social. This was partly because my mother had not been raised on a travel culture. Moreover, she was not terribly adventurous. I recall, even after many years in London, she could not get her head around rain, especially summer downpours, during which she would try to cancel any plans we had, which drew our protests, due to unforeseen, but entirely, foreseeable weather conditions.

England was seen back then as the land of opportunity in Egypt, but it was actually the place where mum abandoned her dreams and ambitions. When mum was younger, she had wanted to be a writer. Given the talent that shines through in her prose, whether in articles or letters home, her originality, even eccentricity of thought, and her deep sympathy for the human spirit and condition, which could verge on the naive, I think she could have become a successful author – she even acted as a muse for a couple of young writers who later became successful, one even naming a character after her in a film for which he wrote the screenplay.

But our household wasn't big enough for two writers, it appeared. Even though mum was the more talented pen and the more authentic voice, it was my father who pursued his career with merciless determination, setting up one failed publishing venture after another. He wanted and expected his newly arrived wife to support him in this endeavour, while he offered her ambitions no encouragement and kept trying to sidestep his responsibilities towards his family, effectively burdening mum with an additional child.

Disappointed that the man she had fallen in love with and sacrificed so much for should be so self-centered, selfish and miserly, mum grew estranged from her husband. Once, she even left home and went to stay with friends of the family on the other side of town. Though I was still too young to understand the finer points of marital discord, it was around this time that mum began to take me into her confidence. Despite missing her desperately during her absence and being unhappy with only my father's presence, even though he did make some attempts to win us over, mainly by curbing his strictness and harshness, I tried to be grown up and support my younger brother and sister through what was to them an inexplicable ordeal. She returned because she missed us and she feared what neglect would do to her children. She dedicated her all to ensuring that did not happen, which included, in addition to managing our lives, trying to earn money to help fill the hole in our finances left by my father's self-absorption.

According to the letters mum sent home, mum going out to work was something my dad strenuously resisted. I'm not sure why, given he was an advocate of female emancipation. I suspect it had something to do with his perceived loss of prestige from the work she was considering and fear that people would say his wife is working because he's failing to support his family, and possibly because of the four kids in whose daily upbringing he did not fancy getting involved.

Mum tried everything she could, but her options were limited. She needed work that she could fit around her kids. In addition, her qualifications were not recognised in the UK and her English was heavily accented and of intermediate level. Then, there was the racism, both spoken and unspoken. Like many immigrants, she ended up doing the work Brits were not so interested in doing themselves, such as working in the Post Office sorting centre and in a series of old people's homes.

My mother even tried her hands at business, an effort I tried to support her in, for example, by helping her design leaflets and correcting her English. However, my mum was not really cut out for the wheeling and dealing of entrepreneurship. Although she had some surprisingly good ideas and she even outlined some to one of my aunts and her husband who were considering moving to the UK as investors, she did not possess the single-mindedness necessary to grow a company, and the enterprise ultimately failed. In addition, it helps to be interested in money if you run a business. And mum, despite dad's regular accusations to the contrary, was almost entirely disinterested in accumulating wealth. Money for her had only two utilities – making her children happy and then making other people happy.

Looking back, I am impressed by how my mother managed, with the limited resources at her disposal, to never make us feel deprived or left out. She usually found a way to finance our clothing, outings, toys, extracurricular activities, gifts for teachers, etc. – I was even one of the first in my school to own a home and then personal computer.

The return to the motherland pounced on us unexpectedly. During the summer holidays, my dad came home from work one evening and had a very solemn conversation with mum. The next day, they informed us that we – i.e. mum and the kids – would be returning to Egypt within a couple of weeks. The situation was tough on my mother. On the personal side, she was thrilled that she would be reunited with her family, whom she hadn't seen, with the exception of one visiting sister, for the better part of a decade. However, she realised that now that we'd spent the better parts of our young lives in England – all his life, in the case of my youngest brother, Osama – returning to Egypt would be tough, especially on me, as I had entered the biological and social shock of puberty and didn't need to compound that with a culture shock. And I was livid with the decision, particularly its unilateral nature and the swiftness of its planned implementation – not to mention that I was happy in my life and was already making plans for the future.

Torn between the desire to go home and her children, mum interceded with dad to try to talk him out of his sudden resolve. But he was adamant – so much so that he turned into an ugly monster. In our remaining time in the UK, friends and others tried to dissuade my father, including my school's headteacher, Mr O'Bourne, who told him that I had a bright academic and professional future in Britain. I was touched that he cared so much.

On the flight, I could sense how thrilled my mother was to be going home. I was excited too, about finally seeing my extended family in Egypt and curious about the country, but sad to leave England and my friends behind and troubled about what this foreign homeland had in store.

_____

Watch this space for part III