Syria and the scent of nostalgia

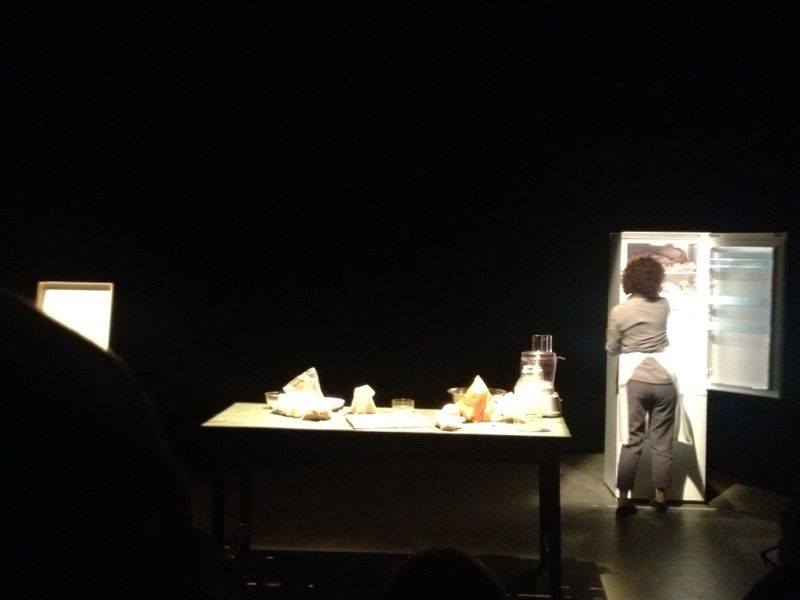

In Oh My Sweet Land, the kitchen acts as the stage where events in Syria are played out, people's fates are sealed and political plots are cooked up.

Friday 9 May 2014

Going to the theatre has always been an event that got my mind, emotions, and senses racing, but never before has a play enabled me to ‘smell' the atmosphere and plot. This all changed during the one-woman show Oh My Sweet Land which introduces a new format of war reporting through an hour-long monologue by the vibrant yet nameless half-German, half-Syrian woman who informs the audience that she will cook a traditional Syrian dish of kubah the way her grandmother's used to, which was her only connection with Syria.

Although she admits that this is her first stab at the recipe, she narrates, while cooking, how her journey began in Paris in search of her married lover, Ashraf, continued to Lebanon, Jordan and eventually Syria, meeting refugees along the way with their various tales. Oh My Sweet Land is directed by the Palestinian theatre-maker Amir Nizar Zuabi and conceived and performed by Syrian-German actress Corinne Jaber, who explore the Syrian civil war through words, as the audience is encouraged to imagine the stories that are being narrated: the brutal bombings, the killings, the torture, the escape and the endless tears.

The kitchen where the play is set acts as the world stage where events are played out, people's fates are sealed and political plots are, quite literally, cooked up. We hear about Ashraf, the narrator's love interest who had fled Syria out of fear of what the security and intelligence services would do to him, but when things back home got worse, he opted to return and be near his people rather than watch helplessly from a distance. As Ashraf's tracks grow cold, the narrator is gripped by the urge to travel to Syria to find him. She heads off in search of her lost lover, only to encounter thousands of Syrian refugees who are suffering far greater losses: each one has either lost a home, family member, friends, a part of their body, or, Syria, their country lost in civil war.

This technically rich and powerful play reveals that Zubai's intention is to focus on the humanitarian crisis rather than the political situation. The Syrian people are the symbolic “meat” in the fridge that is being cooked and shaped to the chef's will, like the kubah and if the kubah does not turn out as it was intended, then it is chucked into the bin, because there is plenty more meat in the fridge. The scent of the chopped onion or simmering meat, which at one point is burnt, gives the audience the chance to experience the ‘smell' of war through the meat that is no longer usable.

Being an Arab who has followed the Syrian situation from the start, the play failed to shock me or reveal anything new, maybe because our world is dominated by visual media and the conflict in Syria has a guaranteed daily news slot. In addition, very few if any actors can manage a whole show by themselves. Although Jaber's performance was exceptional as she progresses through her emotional journey, 35 minutes into the play, your attention starts to slip away and all you are left with are the olfactory stimuli and the question of what will happen to the food that is left onstage.

Jaber's own transformation is one of the more positive aspects of the play, as we observe her grow gradually more connected with Syria, a place she'd had no real longing towards, apart from the nostalgic memory of her grandmother. Her relationship with Ashraf changes this to passion, and her travels turn it into love and regret for a revolution that was hijacked by outsiders. In that one hour, we witness a slow transformation, from a naïve, half-Syrian expatriate who is clueless about Syria and its revolution, to a more experienced and bitter woman. When the play ended, one lady in the audience commented that it deserved a wider audience, as the theatre was only half full. The ideas contained in Oh My Sweet Land are quite challenging and so might not be appreciated by the masses.

Zubai and Jaber were successful in bringing back the old simple way of ‘reporting' the solo narrative voice of someone retelling the stories they were told without being an actual witness to them, symbolising the reality of Syria's situation: everyone has an opinion and everyone thinks they know best, yet no one is really fully aware, nor are they all blameless.

“They call it a civil war but there is nothing civil about it,” says the narrator in anger, which makes you question the role of the people as well as the ones in power. This is echoed further through one of the encountered refugees who wonders if one day we will forgive one another, maybe God will forgive us. We, the audience, are left pondering that same notion: can Syria return to its glory with people forgiving one another to coexist once again in a united country?