Is Hagia Sophia a symbolic bridge or wedge?

By Khaled Diab

The Hagia Sophia must not become a mosque. If its status must change, it should become a space of tolerance, where both Christian and Muslim worship.

Tuesday 16 June 2015

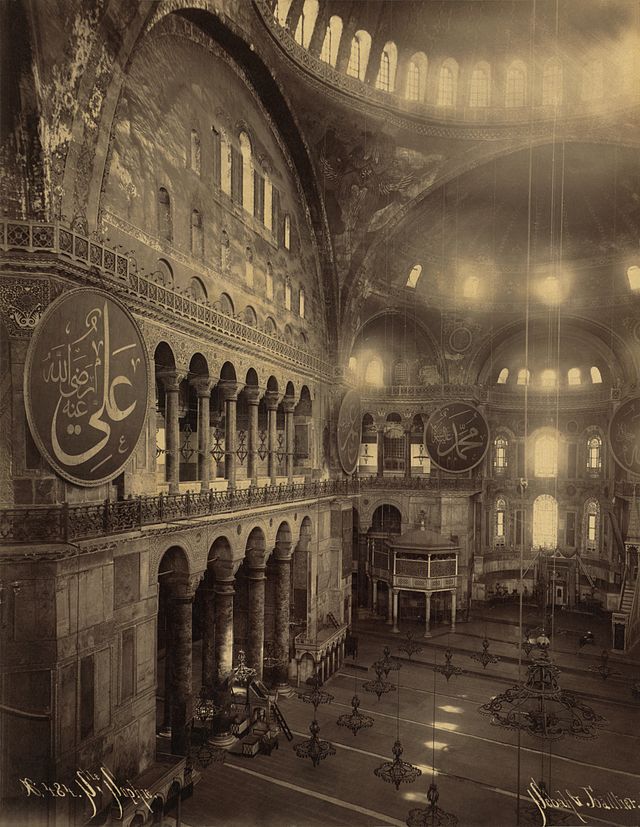

In breath-taking Istanbul, it is perhaps one of the most stunning spots of all: standing sandwiched between the sublime Hagia Sophia and the magnificent Sultanahmet (Blue) mosque which face each other like the intimidatingly gorgeous finalists at a beauty pageant.

Reputed to have been built by Sultan Ahmet I in part to show that the Ottomans could match, and even surpass, the grandeur of the Byzantine splendour of Hagia Sophia, the two majestic edifices show how these two closely related rival religions can sometimes push each other to loftier levels of excellence.

But this rivalry can also plunge to levels of supreme pettiness. Take the hundreds of protesters who recently took part in a rally to demand that the Hagia Sophia museum be converted into a mosque – the latest step in a sustained campaign which has pitted Turkey's Islamists against its secularists.

The Mufti of Ankara, Mefail Hızlı, believes that Pope Francis's decision to recognise the mass killing of Armenians during World War I as “the first genocide of the 20th century” would “accelerate the process for Hagia Sophia to be re-opened for [Muslim] worship”.

Though the Pope's statement reflects the general consensus of non-Turkish historians, the Mufti's remarks betray a profound confusion about Christian history and ideology, such as the famous East-West schism. After all, Francis, born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, is the pope of the Catholic church, while the Hagia Sophia served for nearly a millennium as the spiritual heart of Greek Orthodoxy.

This is yet another telling example of how Eastern Christians have been caught uncomfortably in the middle of the centuries-old rivalry between Western Christianity and Islam. This was most spectacularly illustrated when the Fourth Crusade rampaged through Constantinople (now Istanbul), in what has been described as “one of the most profitable and disgraceful sacks of a city in history”.

And the confusion does not stop with Christianity. Those calling for the one-time Orthodox basilica to be re-converted into a mosque seem to misunderstand Islamic theology too. The Quran clearly demands the protection of churches, synagogues and other places of monotheistic worship.

In a similar spirit, the prophet Muhammad sealed numerous covenants with Christian and Jewish communities, including the monks of Mount Sinai, which protected their freedoms and their holy places.

This concept was eloquently expressed at another magnificent church in another sacred city. The second caliph, Umar Ibn al-Khattab, showed considerable foresight when accepting the surrender of Jerusalem after a bloodless siege. When invited by Patriarch Sophronius to pray with him in the Holy Sepulchre, Umar reportedly refused out of fear that “Muslims of a future age would have infringed the treaty under colour of imitating my example.”

Umar's attempt to avoid this outcome by praying in an open space nearby did not completely avoid this fate. And true to his expectation, a few centuries later, the Ayyubids built a mosque where Umar had prayed, a short distance away from Christianity's holiest church.

Despite these clear injunctions and precedents, there is, unfortunately, a long history of important churches being converted into mosques. These include the Umayyad mosque in Damascus – which had previously served as an Aramaean and Roman temple, before it became a Christian cathedral – and the Hagia Sophia itself, which Sultan Mehmet II insisted should become a mosque upon his bloody conquest of Constantinople.

And it is to the five centuries during which the Ayasofya served as a mosque until Ataturk converted it into a museum that Islamist nostalgists wish to return . But in addition to conflicting with the spirit of the faith they claim to follow, this has dangerous symbolic consequences for the future.

If modern Turkey which has a reputation for secular tolerance and a tradition of moderate Islam converts this enormously significant monument into a mosque, what signal is this sending out to jihadists and other radicals?

At a time when Christians in the Middle East need the support and solidarity of their mainstream Muslim compatriots, this would constitute a slap in the face and may further embattle their increasingly precarious and vulnerable position.

At a time when Islamophobia is on the rise in Europe, a highly symbolic move like this can be exploited by anti-Muslims to further stigmatise and marginalise European Muslims, including three million people of Turkish origin in Germany alone.

In these troubled times, it would be best for Turkey to take a leaf out of the annals of Islamic tolerance rather than its chapters of intolerance, and fulfil its longstanding potential as a bridge between “East” and “West”, between “Islam” and “Christendom”.

Personally, I prefer the idea that the Hagia Sophia should remain in its current form, a museum where all of humanity – be they people of faith or not – can come together and admire the beauty of human creativity and dedication.

However, if it must again become a place of worship, then this magnificent space should reflect its long history as both a church and a mosque. If Muslims and Christians both worship in this single space, it would send out a powerful message of coexistence at a time when the forces of intolerance are mounting a major assault on our common humanity.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This article first appeared on Al Jazeera on 7 June 2015.