Defining Egyptian democracy: “Not like America and not like Iran”

Provincial Egyptians believe that moderate Islamists can construct an Egyptian model of democracy that respects their traditions and identity.

Tuesday 20 December 2011

While on a research trip to Luxor, I decided to find out for myself what the ordinary people of Egypt really wanted from the revolution and to see if that matched in any way what was being reported in the UK's popular press. So I donned my hijab, and my partner and I wandered the city for a few days before setting off and visiting the villages on the west bank of the Nile. We talked to a wide range of people over the space of a week, including a former English professor, hotel workers, farmers, felucca owners, beggars, shop keepers and women street vendors.

It became clear very quickly that, although language was not a barrier, vocabulary and its understanding was. People spoke freely, often with passion, with desperation at times and with a joy at being able to voice their opinions. They all, without exception, voiced fear of a religious government, a wish to have order, a fair share of wealth and proper jobs. The fear of a strict Islamic government was very clear, but there was also distaste for a Western-style amoral society. And that was the first hurdle of vocabulary for me to overcome. When someone says to me they do not want a religious government, I assume they want secularism. When in fact what most of the people seem to want is something in the middle, which would explain the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood.

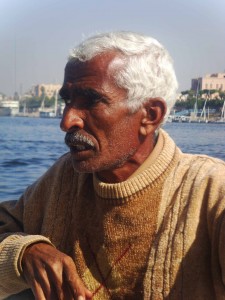

“I don't want to have to grow a beard and shut my wife up, but I don't want that either,” said one felucca captain as he nodded at a passing tourist, female, in very little clothing. There is a strong belief on the streets of Luxor that secularism means decadence, greed, corruption and a lack of morals. His tale, like many of the personal stories I had in that week, was very sad. A man in his 60's, very well educated, very well travelled, he could not get work anywhere except shunting tourists up and down the Nile for 20 Egyptian pounds (£2 sterling). He studied English literature, taught in Cairo in his younger days and travelled throughout Europe with his wife (she is my all, he said wistfully). He is also a practicing Muslim and feels that a life without God is no life. These days he wanders the east bank of the Nile, quoting Shakespeare to tourists in the hope of catching the attention of someone, someone who will hire his boat, someone who will pay him a pittance, so he can get through another day.

I asked him about the situation between Copts and Muslims, as it does seem to be an issue according to the UK news. “Pah” he says, “Luxor is 40% Copt, they are our brothers and sisters, our family. We have no problems between us. Our only problems are from the beards. By the way, don't believe everything you hear on al-Jazeera.” I asked him if he had worked today. “No,” he said, “I have not had work for a week, thanks to newspapers scaring away tourists. You were not afraid to come, tell people to come, please.” I told him that I had spent a lot of my childhood visiting Belfast, during the early 70's, and that it takes a lot to scare me off. We could not leave him in such a way, so my partner hired him for the afternoon, at English rates, so they could chat further as they drifted down the Nile. I set off to wander the streets, to find other voices, other opinions.

“Come see my shit” was the opening line of a shopkeeper desperately trying to drag me in from the streets to ‘buy his shit'. I declined to make a purchase but we ended up chatting over hibiscus tea and tobacco. It did seem to be a good ‘drawing tool', the fact that I dressed as an Egyptian woman and rolled my own tobacco. People were fascinated. They first assumed I was smoking hashish, but when I explained that it was just tobacco, they wanted to join in, drink tea and talk to this rather bizarre woman. Two other shopkeepers came, their business almost dead, to join in the tea and company. I asked them what life has been like since the revolution began and what their hopes for the future were.

The first thing that everyone mentioned was the absence of policing, the lack of regulation in the city that was causing mayhem for the shopkeepers. They bemoaned the fact that tourists had been scared away by reports of riots, and that the upcoming elections (2 days later) were confusing. There were many candidates, too many probably, and no one seemed to know what they stood for, who they were and what they would bring to society. Small images, often unrelated, identified the candidates and when I asked what the candidates offered, the shopkeepers shrugged. Do you want a secular society I asked. “Like America?” Yes, I replied. “No, we do not want that sort of mess.”

“Do you want a religious government, like Iran?” The men fell about laughing. “NO,” they all shouted in unison. “We want a government which is fair, not religious, that works for everybody and doesn't tell us what to think.”

This highlighted for me the problem with vocabulary and understanding yet again. It would seem that people equated secularism with a decadent society of greed, disrespect and degeneration. I was beginning to see how the Muslim Brotherhood's Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) was being so successful in the elections. They promise compromise, pragmatism and social justice.

“And if we do not like who gets in to government, then we will just kick them out again” was the parting words of one shopkeeper. It would seem that the people of Egypt had finally found a sense of their own power. As I walked back to my hotel, I came across a woman sitting by the side of the road, a pile of colourful scarves in her arms. She did not have the energy to chase the occasional tourist, instead she sat, holding out her arms as people walked by. I went and sat by her, bought some of her wares to ensure she had money for that day, and got into conversation with her. She was a divorcee, supporting her three children alone, and despite having a good education, the only work she could get was selling trinkets to tourists. What were her hopes and fears for the future of Egypt?

“I am afraid of Egypt becoming like Iran, that is my biggest fear of all for the future. I am a Muslim, I love my family and I work hard, but I want our government to work for all of the people. I don't think government should be religious, that is not it's job.” So I asked if she wanted a secular government? No she replied, “People who do not believe in God cannot be good people.” It was becoming very obvious that ‘secular' was being equated with ‘atheist'.

“What about a government made up of Muslims, Copts, etc., which just worked on government issues and not religious law? “That is the FJP, they will do that,” she replied. I hope she was right, I told her.

The following day, I set off the to the west bank villages, the place where the farmers and urban manual workers lived. I struck up a conversation with a middle-aged sugar cane farmer who was curious as to why a woman in hijab was rolling tobacco (it always peaks curiosity and curiosity is the biggest opener of doors). I rolled him a cigarette and he produced the tea. It was a long and interesting conversation that would probably not have happened only 12 months ago. He was scathing in his attack on the government ,both now and under Mubarak. So I asked him what it was about the current government that was making him angry. “Corruption,” he replied, “corruption at every level”. Nothing had changed for him except that there was more crime on the streets now. He told me that, as a farmer, he sold raw sugar to the government for 90 Piastres a kilo. He then had to buy it back as processed sugar for his family at 7 Egyptian pounds a kilo. He could not understand why he got so little for his product and yet so much profit was obviously being made. We began talking about society in general and where he felt Egypt was heading. He spoke a lot about the region needing a sense of ‘right and wrong', of a moral society that cared for all people. I asked him if he meant a Muslim Government. “Yes” he replied.

“Like, say, Iran for example?”

“Oh no, not like that, that is not Islamic anyhow, that is just ignorant bullying.”

So I asked him about the Muslim Brotherhood. Did he think they could do a good job? He nodded vigorously. “Yes, they care for our brother Copts as well as us. They care about all of us and they respect the poor. They will look after us, all of us.” So I ventured into more searching questions, and asked his opinion on the more traditional al-Nour party. The man shook his head while kicking the dirt at his feet. “We want our way, the Egyptian way, the respectable way, but we do not want to have to grow beards, we do not want to go backwards. We want to go forwards, but be respectable. You dress like a good Egyptian woman, you know what I mean.”

I nodded, I was beginning to understand. I asked him if a lot of people will vote tomorrow (Luxor elections) for al-Nour? He nodded sadly. “There are too many candidates, it's too confusing and people are frightened. They are fearful of corruption, of decadence, of poverty. If someone says they will give money to the poor, they will get votes. We are also worried about becoming like the West. We are not the West, we are good people, we work hard and respect our families. We want tourists to keep coming, to bring their money, we do not want to be like Iran.”

It struck me that the Iranian model was none too popular and was frequently used as an example of what people did not want.

As we spoke, a group of young boys were touting trinkets to tourists. They were fashionably dressed and could have walked straight off a New York street. They chased the scantily clad tourists mercilessly, physically grabbing the women, and making a general nuisance of themselves. One of them spotted me rolling a cigarette and wandered over in curiosity. “You give me hashish?” said a boy who can't have been more than 10-years-old. I waved him away as the farmer I was talking to shook his head. He nodded at the boys, whose passing comments to women would have turned a corpse red, and pointed out that he felt his whole country would become like them if they had a “godless” government.

My last interview victim was a Copt working in the city of Luxor. I was staying in a Coptic-owned hotel and had chatted with the staff throughout the week. He pointed out to me the need for elections sooner rather than later: the lack of stable government at both the local and national level was creating chaos on the streets. Too many taxi drivers, no policing: the country needed regulation and soon. What about the Muslim Brotherhood? “They will be ok, I think, but the Islamic parties are a worry if they get in. If they do, I am moving out.”

I pointed out that the Brotherhood is an Islamic party, and is seen in the West as a potential threat to democracy. The man smiled and shook his head. “We have nothing to fear from them, they are about government, not religion, if they know what is good for them and for Egypt, we will have a democracy with them. And if they do turn out to be too religious, then we will kick them out.” Yet again, this expressed the new sense of popular confidence and people power on the streets.

What about secular parties, I asked? “Liberals? La (no). What do they know of family responsibilities, they are not respectable people, they are not Egyptians,” was the Copt's dismissive reaction.

Later, I sat by the Nile and pondered over the voices I had heard over the week as I watched the military trucks filled with soldiers park quietly up the back streets in preparation for voting. One thing had become patently obvious: the secularist parties were not listening to the people, to the ordinary rural folk trying to get through life with some dignity. The people needed straight talking, down-to-earth practical understandable solutions, agendas and a manifesto that fitted Egypt, not the West. Instead they bandied about concepts and issues that the local people could not relate to, and most important of all, they have done nothing to truly connect with the ordinary, everyday person outside of Cairo.

Maybe the FJP would be a good bridge to the future, if they kept in mind that the people will no longer tolerate oppressive rule. That would give the liberal parties chance to get their act together and find a way to speak for all of the people, not just the educated middle classes. This is a major turning point for Egypt and it has to work from the inside out, it has to come from the people, all of the people. Personally I think at this point in the game, a western style secular free market economy would be a cultural disaster for Egypt, it certainly is not the answer to all ills, as we are finding out in the west, for a number of reasons. There has to be a way to have a socially conscious government without religion being involved. Maybe Egypt will birth something new, a socially conscious society that is intellectually free and a government that keeps its nose out of people's hearts and minds. We can all live in hope of such a dream.

A well written and thoughtful article. Thank you.