Enslaved by the history of slavery

By Khaled Diab

Failing to acknowledge the legacy of slavery on all our modern societies makes the present an unnecessary slave to history.

Wednesday 13 May 2015

Like Ferguson before it, the upheavals in Baltimore have been linked by numerous historians to the legacy of slavery. Describing the United States as originally a “slave holder's republic”, historian Gerald Horne explained, which led to a view of Africans as “the enemies of the republic”, resonating right down to the present. “The origins of [the] urban police department lies precisely in the era of slavery. That is to say, slave patrols,” he added.

While the impact of slavery and then segregation are clear to see in the poverty, marginalisation, mass incarceration and prejudice with which African-Americans have to live, it is by no means a uniquely American experience – the whole world is struggling to deal with the legacy of one human claiming ownership of another.

Owing to its superpower status and the harsh cruelty of its particular brand of enslavement, the American experience has become the global benchmark. But the reality of slavery is far more diverse. Although Africa is the continent most bled by slavery, slaves have been of all races, nations and groups. The very word “slave” refers to the “Slavs”, who were a major source of slavery in medieval Europe.

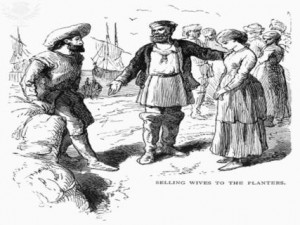

Even in the Americas, there were some white slaves, who predated their black counterparts at a time when Africans were too expensive to be economically viable. For the British, the earliest source of slaves for their American colonies were drawn from their prototype colony, Ireland.

Image: http://immigrationmuseum.wikispaces.com/2.+Indentured+Servants+and+Slaves

England's blood-soaked re-conquest of Ireland in the 17th century – led by theocratic dictator and Protestant Puritan Oliver Cromwell – involved clearing vast swathes of the country of its Irish Catholic inhabitants. Many thousands of the displaced were sent to the Caribbean as slaves.

Some historians who remember this forgotten episode prefer to use the term “indentured servant” but, to my mind, this is just a euphemism for slave, since these so-called servants were “personal property, and they or their descendants could be sold or inherited”. In fact, an English adventurer of the time described these hapless Irish as “derided by the negroes, and branded with the Epithet of ‘white slaves'”.

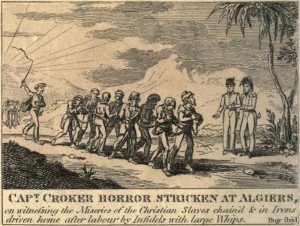

By one of those quirks of history, this brings us to another Baltimore, this time in Ireland. In 1631, this village in Cork was sacked by Barbary pirates, whose inhabitants – mainly English settlers whose compatriots would a few years later enslave the Irish – were carried off into slavery.

Between 1530 and 1780, these Muslim pirates captured up to 1.25 million Christian Europeans, according to one estimate, causing the inhabitants of many coastal areas of Europe to flee in fear.

From our contemporary vantage point after centuries of Western global dominance, it is hard to fathom that Europeans were ever slaves. But Middle Eastern slave markets were well-stocked with them. These included, at various periods, Caucasians (i.e. from the Caucasus), Slavs, Albanians, Greeks and even Norsepeople.

However, owing to the Islamic restrictions on enslaving “people of the book”, by the 14th century, Africa was the primary source of slaves in the Middle East. Perhaps as many as 14 million Africans were carried off into slavery by Arabs/Muslims, comparable to the Transatlantic slave trade, albeit over a longer period.

Slavery in the Arab and Muslim world differed significantly from that practised in the Americas. Though, like in America, many slaves were engaged in back-breaking work in abysmal conditions, perhaps the majority were employed as servants, concubines and soldiers. In addition, freeing slaves was considered a noble act in Islam and, hence, many were liberated.

Moreover, not all were of a lowly status. A fortunate minority of slaves enjoyed a higher social status than free men and women. For instance, one of the most creative eras of my native Egypt's history occurred under the Mamluks, slave warriors raised to rule, and the only woman to govern Egypt in the Islamic era was Shagaret el-Dur, a former slave girl. But I'm doubtful that such prestige or power compensated its holder for the early trauma of being kidnapped from their family and regarded as someone else's property.

Though viewed more negatively, African slaves, too, could rise to high positions of influence. One example of this was the position of Kizlar Agha, the Ottoman chief eunuch and the third most influential position in the Sultan's court.

For various complex reasons, slavery took longer to die out in the Arab world than in the West, with the countries of the Gulf not abolishing it until the mid-20th century. Despite this, the social, economic, political and cultural legacies of slavery are given very little attention in the Arab world.

For example, though the long and diverse history of slavery in the Arab world means that just about anyone of us could have a slave as an ancestor, the insult “abeed” (“slaves”) – which has even made it across the Atlantic – is only used to deride those of African extraction. Alongside classicism, the legacy of slavery also colours the attitudes of some Arabs towards domestic servants and migrant workers.

Few Arabs I've encountered ask themselves how does the history of slavery affect our relationship with the places where slaves originated and how they perceive us. Within our own societies, this legacy can lead to discrimination and can help facilitate the exploitation of bonded labourers.

Failing to acknowledge and challenge the impact of slavery on our modern societies makes the present an unnecessary slave to history.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This article first appeared on Al Jazeera on 8 May 2015.