The Arab media paradox: Free expression amid repression

By Khaled Diab

Frustratingly for Arab dictators and despots, no matter how much they try to silence, intimidate or co-opt the media, new loud and critical voices emerge.

Wednesday 11 May 2016

It is not just the news that is depressing. The state of the media around the world is increasingly becoming a cause for alarm. Tuesday 3 May was World Press Freedom Day and almost everywhere you turn your gaze, media freedom is under threat from governments, terrorist organisations, crime syndicates and corporate interests.

Freedom House's latest report found that global media freedom was at its lowest level in a dozen years.

According to the Washington-based watchdog, only 13% of humanity enjoys access to a free press. Even in countries where freedom of the press is legally protected and supposedly sacrosanct, the media is experiencing mounting pressure, as governments exploit the threat of terrorism to enact restrictive legislation and populist right-wingers find ways to co-opt or muzzle the media.

A similar message is echoed by France-based Reporters Without Borders whose latest Press Freedom Index (PFI) has registered a growth in violations of nearly 14% since 2013. This reveals “a deep and disturbing decline in respect for media freedom at both the global and regional levels” which “is indicative of a climate of fear and tension combined with increasing control over newsrooms by governments and private-sector interests”.

These violations can verge on the insultingly absurd. An example that would ring familiar with many Arabs was the case late last year of a Thai man who was arrested for “lèse majesté” late last year for allegedly “insulting” not the ailing King Bhumibol himself but his beloved dog in a series of Facebook posts. As is often the case, the real target of the junta's ire are the allegations the same man published about widespread corruption in high places.

In both rankings, the turbulent and conflict-ridden Middle East props up the bottom half of the global league and, according to Reporters Without Borders, is “one of the world's most difficult and dangerous regions for journalists”. Freedom House concurs, noting that “governments and militias increasingly pressured journalists and media outlets to take sides, creating a ‘with us or against us' climate and demonising those who refused to be cowed”.

Journalists here are at risk from repressive regimes and their security apparatuses, armed militias and terrorist groups, religious radicals, not to mention the threats posed by regressive laws, those above the law or general lawlessness, depending on the location. With all the dangers to life and livelihood which independent media professionals in the region experience, it is almost a miracle that anyone would make journalism their career choice.

The main good news about the region's media emanates from Tunisia, the only Middle Eastern country to rise in the PFI rankings. But even in the Arab uprisings' greatest success story so far, journalists still face regular harassment and often exercise self-censorship.

The largescale war against media freedom in the Arab world actually distorts a key and perhaps paradoxical truth: never have Arabs enjoyed freer access to information and never have the region's journalists and citizens mounted such a constant, consistent and comprehensive assault on the state's media dominance. This is especially the case in the frontline states of the Arab revolutions.

The most incredible and laudable examples of this must be the journalists and citizen journalists working to record and broadcast the truth in the region's war zones – Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Libya.

Despite being the deadliest country for journalists in the world, many Syrians continue to put their lives on the line to report on the crimes and violations of the Assad regime, ISIL and other armed groups. One of the most dramatic examples of this is the award-winning ‘Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently', a citizen-journalist group reporting independently out of ISIL-controlled territory.

Although government crackdowns have narrowed the space for free expression, frightening and cowing many in the process, the region's courageous independent journalists have been forcing open the cracks left behind.

In this regard, the digital and social media have been a lifeline. Two prominent examples of this are the audacious and daring investigative journalism sites Inkyfada in Tunisia and Mada Masr in Egypt.

For their part, regimes have been fighting back. Not only have Arab governments invested heavily in surveillance and monitoring technologies, they have also sought to beat activists and revolutionaries at their own game by building up a dynamic propaganda presence online.

But frustratingly for Arab dictators and despots, no matter how much they clampdown on free expression and try to silence, intimidate or co-opt the media, new loud and critical voices, whether underground or in broad daylight, invariably emerge.

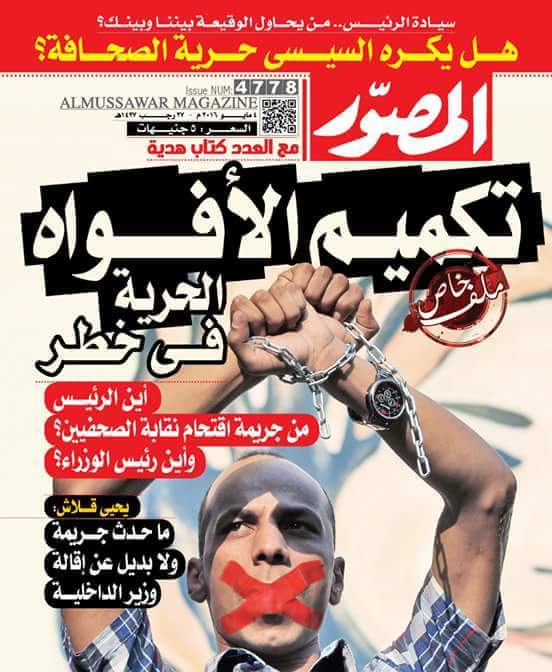

This was amply been demonstrated by the remarkable media and protest campaign spearheaded by the Egyptian Journalists Syndicate to defend press freedom, call for the resignation of the interior minister and demand an end to repression.

Although the days are long gone when Arab regimes enjoyed a near monopoly on the flow of news and information within their borders, they still act as though they can control the minds and consciousness of their citizens.

Once upon a time, Arab leaders could figuratively parade without clothes in front of their pliant media and hypocritical “Yes men” and nobody would dare tell the emperors they were nude. Though our leaders would love nothing more than our turning a blind eye to their naked lust for power, millions of Arabs are no longer willing to applaud our emperors' new clothes. The Arab public has become unwilling to accept illusion and delusion as substitutes for actual change.

It is high time for Arab governments and other repressive actors to learn that the wise way to deal with criticism is not to shut down critical media but to respond to and engage with opponents and critics, and to enact meaningful and deep reforms.

____

Follow Khaled Diab on Twitter.

This is the updated version of an article which first appeared on Al Jazeera on 3 May 2016.