For Buddha and country in Sri Lanka

The toxic Buddhist-Sinhala supremacism and triumphalism in Sri Lanka means the country's fragile “peace” is just the prelude to another war.

Wednesdaw 18 September 2013

“The most dangerous creation of any society,” the late American novelist James Baldwin wrote in 1963, is “a people from whom everything has been taken away, including, most crucially their sense of their own worth.”

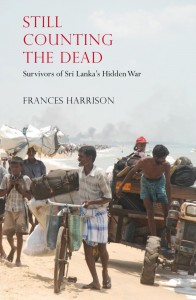

In Still Counting the Dead, an extraordinary account of the savage denouement in 2009 of Sri Lanka's protracted civil war, Frances Harrison introduces us to such people: Tamil survivors who, displaced from home, are now dispersed across the developed world's detention centres and immigrant neighbourhoods. A former BBC correspondent in Sri Lanka, Harrison travelled to Australia, Britain, Norway, Germany and other undisclosed places to interview the war's survivors. Their testimonies have no silver linings. They have escaped the fighting, but are captive to its experience. And they see in the reluctance of the world to recognise their loss an extension of the torment they endured on the battlefield.

The war itself was the culmination of a dispute that has been raging, with varying intensity, for millennia. Its origins can be traced back to the arrival in Sri Lanka, around 2,500 years ago, of Vijaya, a thuggish prince banished from his father's kingdom in eastern India. Vijaya, the legend goes, married an indigenous ogress and established his rule over the island. This, at any rate, is the origin myth of the Sinhalese, who constitute the overwhelming ethnic majority of present-day Sri Lanka. The Tamils, emanating from the nearby peninsula of southern India, claim that their settlements predated Vijaya's arrival. The Sinhalese embraced Buddhism, the Tamils remained largely Hindu, and there were occasional battles on the island. But on the whole the two communities cohered, if not in peace and harmony, then in cordial hostility, for more than 2,000 years. Sri Lanka generated a composite culture.

Then modernity arrived in the form of Western imperialism, overhauling ancient pluralism and exposing native elites to its most insidious ideological innovation: nationalism. Influential Sinhalese voices soon began clamouring for the creation of a “pure” homeland, rid of not just the British but also the supposedly treacherous Tamil newcomers they had brought along to work the tea plantations, banishing the ancient Tamil presence on the island to an exile beyond the popular consciousness.

In language borrowed from European demagogues of the early 20th century, Sinhalese nationalists demanded the restoration of an unadulterated past that had never truly existed. The powerful Buddhist revivalist Anagarika Dharmapala claimed that the Sinhalese were an “ancient, historic, refined people” who had transformed Sri Lanka “into a paradise” – only to see it destroyed by the “barbaric vandals” in their midst. Invoking religious histories, and citing colonial surveys and dubious ethnographies, Sinhalese chauvinists fabricated a hierarchy of citizenship within Sri Lanka and demanded corresponding political privileges for the majority. This was self-empowerment through exclusion – a majority that sought to validate its dominant position by placing minorities directly beneath itself.

Once British rule ended in 1948, the early governments of independent Sri Lanka resisted this majoritarian impulse. But theirs was a feeble attempt. By 1972, Sinhala chauvinism was enshrined in the country's constitution. Sinhala was made the sole official language of the state, Buddhism the favoured religion, and minorities were pushed to the margins even on the national flag: the sword-wielding lion, the Sinhala totem, occupied the centre. Bigotry was now backed by the law. Tamils could not gain admissions to universities, did not have access to the language of the law, and were erased from the symbols of the state. And yet the country's Sinhala overlords expected them to pledge allegiance to Sri Lanka.

Politically conscious Tamils scattered into various protest forums. Their appeals for equality within Sri Lanka, however, were rapidly eclipsed by the separatist cry for Eelam – a Tamil homeland carved out of the country's northeast. The fight for Eelam was led by Velupillai Prabhakaran, a formidable Tamil guerrilla who founded the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in 1976. The LTTE heralded its arrival by slaughtering thirteen Sri Lankan soldiers in 1983. Sinhalese mobs reacted by butchering thousands of Tamils living in the country's south. Sri Lanka's civil war had begun in earnest.

Differences that could conceivably have been resolved through dialogue dragged on for decades on the battleground, hardening into a stalemate. India at first eagerly boosted the LTTE. Then, as if to create a balance, it engineered a brittle peace accord between Colombo and the Tamil nationalists and dispatched its own peacekeeping forces to Sri Lanka to monitor it. But Indian soldiers, far from keeping the peace, engaged in hostilities with the LTTE. Tamils accused Indian soldiers of raping and murdering civilians. The Indian mission was a disaster. New Delhi pulled out. War re-erupted in Sri Lanka.

Funded mainly by expatriate Tamils, the LTTE gradually grew into a sophisticated terrorist organisation. It pioneered the use of suicide bombers, one of whom assassinated Rajiv Gandhi in 1991 in retribution for his decision, as prime minister of India in 1987, to send Indian troops to Sri Lanka. Prabhakaran, an unyielding zealot, proved he was also a fool, alienating with this single move the region's major power. For an entire decade, the LTTE became non grata in India.

Then 9/11 happened and the LTTE, listed internationally as a terrorist organisation, lost its legitimacy. Sinhalese nationalists seized the moment. Prabhakaran, a military tactician, could not comprehend the political shift that had occurred. He ordered Tamils to boycott the crucial presidential elections in 2005. Had they voted, the relatively moderate Ranil Wickremasinghe may well have won Sri Lanka's presidency. Their boycott resulted in a narrow victory for Mahinda Rajapaksa.

A ruthless nationalist and a fierce believer in Sinhalese supremacy, Rajapakse waited for two years before unleashing his forces on the Tamil scrublands to the country's north. Prabhakaran had mismanaged the Tamil cause so thoroughly that as the Sri Lankan forces marched into Tamil strongholds by April 2009, pulverising everything in their sight, none of Sri Lanka's neighbours made a noise. Echoing the indifference of the governments, the world's leading news media stayed away. More than 60,000 people were killed in the last three months of the fighting – yet there wasn't a single foreign reporter on the ground.

As the government forces penetrated the rebel territory, Tamil civilians retreated further north, halting only when they became trapped between the advancing soldiers and the sea. The “safe zones” designated by the government for civilians were in fact death traps. Harrison tracks down a Tamil journalist who filed reports from the scene for as long as he could before crossing over with his father in the last weeks of the war to the government side. Every step of their journey became a prolonged arbitration with death. Corpses were strewn everywhere, jets pounded the land from the skies, and soldiers fired from all angles. Finally, when they reached the government side, father and son were stripped. An old man and his young son standing naked in a long queue of displaced people, all awaiting interrogation: Harrison's prose frequently evokes such harrowing images. They were the luckier ones.

A Tamil shopkeeper with shattered legs, currently seeking asylum in Australia, recollects being taken from a hospital and made to witness five executions, each with a single bullet to the back of the head. It's as if Sinhalese soldiers, long accustomed to imagining Tamils as indomitable agents of mass murder, erupted with an uncontainable fury after vanquishing them. Trophy videos recorded on mobile phones show Sinhala soldiers summarily executing blindfolded Tamil men and piling up trucks with naked corpses of raped Tamil women. Harrison meets a young female refugee in London, the wife of a possible Tamil Tiger collaborator, who was picked up from her home, taken to a villa to identify a group of blindfolded men, and then locked up overnight in a room and raped by two soldiers. These are the twice-humiliated: physically defeated by war, psychologically desiccated by its winners.

Despite her sincerest efforts, Harrison can at times seem too lenient in her cross-examination of the Tamils she meets. She interviews a young Norwegian Tamil who travelled to Sri Lanka in the hope of becoming a suicide bomber. He was raised in Norway, didn't speak any Tamil, and it's not clear if he had any Tamil friends. What is the proper reaction to his conduct? Is it to endorse, by offering sympathy, his self-image as a freedom fighter? What of the Sinhalese children and mothers and fathers whom he would have murdered had his tender ambition of blowing himself up been realised? Is it proper then to restrain or even a kill a person who, if left untouched, would distribute death among innocent civilians? Harrison doesn't probe such questions.

It is to her credit, however, that she acknowledges the limits of her project at the outset: the plight of the Tamils. But the question remains: if the comforts of Norway and the complete isolation from Sri Lanka couldn't anesthetise the Norwegian to the “cause”, how, having witnessed the horrors of the war, is this young man now likely to behave? Has the dream of becoming a martyr for the “motherland” really abated?

Perhaps these are questions better left to the Sri Lankan government and the Sinhalese nationalists who form its support base. The current generation of Sinhala nationalists, filliped by victory, have become afflicted with triumphalism. They cannot abide any criticism of the state. The overwhelming evidence of war crimes, compiled at great personal risk by individuals like Harrison, has failed to elicit even the slightest admission of wrongdoing in Colombo. Foreign activists are barred from entering the country and domestic campaigners for accountability keep disappearing.

Democracy is almost dead in Sri Lanka. Virtually every important government post is now held by a member of the Rajapaksa family. And rather than striving to heal Tamil wounds, their government is busy scratching them. President Rajapaksa recently inaugurated a luxury hotel in the Tamil heartland for the comfort of Sinhala chauvinists touring the battlefields where their ethno-supremacist narratives were so violently confirmed.

But as Harrison hints, far from coming to a permanent end, the long conflict between the Sinhalese and Tamils has graduated to a new phase. The only insurance against another outbreak of fighting is to reinvent Sri Lankan nationalism in ways that will make it possible for all of its citizens to assert their identity. Sri Lanka will have to return to the political drawing board and revise the constitution to diffuse among all its inhabitants the privileges that are reserved exclusively for the Sinhalese. But Rajapaksa, busy atrophying Sri Lanka's independent institutions, stands in the way of such a reconciliation. His immense network of executioners and torture chambers cannot, however, produce a lasting peace.

“Force”, as Baldwin wrote, “does not work the way its advocates seem to think it does.” Far from exhibiting strength, it reveals only “the weakness, even the panic” of its proponents, and “this revelation invests the victim with patience”. Ultimately, Baldwin warned, “it is fatal to create too many victims”. Rajapaksa has done exactly that. The volatile peace he presides over is only a prelude to another war.